SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – RENT was once bigger than its legacy.

Staged for the first time in 1993 at the New York Theater Workshop, RENT was loosely adapted from Puccini’s La Bohème, transforming the Parisian opera from the 1800s into a rock musical about bohemians living in Alphabet City amidst the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the late 1980s. Now, 31 years after its off-Broadway appearance and 28 years after its Broadway debut, RENT has amassed an unparalleled reputation – spawning countless restagings, revivals, and tours, on top of a revolving door of cast members to pick and choose from.

Do you want the 2005 film starring most of the original cast? The filmed final performance on Broadway in 2008? The travesty of RENT: Live in 2019? The slime tutorials? With the mounting of RENT in Manila for the fourth time, how does one begin to evaluate a musical that’s been staged and discussed to oblivion?

Parallels, differences

It’s easy to dismiss RENT as outdated material and each staging must often justify its existence. But parallels between yesteryear’s New York and today’s Manila are easy to draw – with both milieus suffering from gentrification at the hands of the corporate elite, widening wealth gap pushing people below the poverty line, brutality and corruption at the hands of overfunded police and army, and most terrifyingly, the growing number of people living with HIV, especially in the 15 to 24 age group.

It’s low-hanging fruit to discuss RENT merely on the merits of its cast. It is far more urgent and less common to see examinations of its staging, the politics and power dynamics of its inclusions and omissions, and the ways American collective memory can connect to our own fraught history and present.

Having directed two prior iterations locally, RENT director and 9 Works Theatrical Artistic Director Robbie Guevara is aware that it’s difficult to make the production new without sacrificing its best qualities. This iteration of RENT doesn’t have the same New York grit nor hardened edges and vocals that define the material. Instead, it is softer and more proactively highlights the camaraderie that forms the backbone of New York society.

Moments in the musical that are mere suggestions of community – notably “Life Support,” “Another Day,” and “Will I?” – become magnified. Using the three-story steel scaffolding of Mio Infante’s scenic design, Guevara creates tableaus of New Yorkers desperate to connect in an urban space that pits them against one another.

In “Life Support,” Guevara highlights the strength often mustered in the presence of others. He overturns this image in “Will I?” by confining individuals from the support group into frames of their own suffering, their lives distinguished by metal railings and Christmas lights. Alone in the privacy of their homes, this strength is much harder to muster. It’s a decision that grounds the material in the musical’s hidden truth early on: people need people. Most notably, the support group interacts with one another onstage during intermission, their bodies bathed in rainbow colored light just before “Seasons of Love.”

Other times, the direction doesn’t align with the material’s values. In Santa Fe, a number sung by computer wizard Tom Collins (Garrett Bolden) that narrates their aspirations for a better life in New Mexico, Guevara and choreographer PJ Rebullida put the three leads on the three-story steel structure while the rest of the homeless act out the trio’s imagined utopia on the ground, inadvertently gentrifying and segregating even the dreamscape.

The focus on the community is noble. But by putting the HIV so explicitly at the forefront of RENT, Guevara unintentionally isolates disease from the milieu instead of depicting its intersectionalities with larger inequities that exacerbated it; at times detracing power from other political mismanagements within the work. Crucial to understanding the HIV epidemic in the 1980s is how it ravaged the East Village silently as a shadow just as homelessness and the fiscal crisis took New York City under its grip, creating a population that was more interested in entertainment and celebrity than the challenges of their neighbor.

Hits, misses

RENT’s narrative structure and dramaturgy is influenced by the process of viral infiltration and as a text, it introduces only the threat of the virus in the first act, cushioned by the availability of the miracle drug AZT (inhumanely priced at $8,000 to $10,000 a year), buried underneath the spectacle of the revolution. Only in the second act does it make us feel the way it ruptures the community. Its persistence in the underbelly of the East Village and the swiftness with which it took lives away is why it was not taken seriously as a health crisis.

Angel’s sudden death embodies the title’s dual meaning – the cost of temporary occupation, but an allusion to this spiritual disconnection. Adrian Lindayag, his second time in the role of Angel, is brilliant because of the gravitational pull he exerts. His presence draws out unexpected levity from strangers (“Today 4 U”), with Angel becoming almost like a biblical example of goodness. So when he dies spectacularly in a fever dream, symbolized by a drop using aerial silks (“Contact”), creating a picture reminiscent of Gustave Dore’s “The Fall of Rebel Angels”, a black hole replaces him in his support group chair.

Most antithetical to Guevara’s directorial vision of RENT is its music. It’s not as if the cast and band are untalented. But Daniel Bartolome’s musical direction doesn’t take advantage of their talents nor does it seem to have the reverence for or even an interpretation of the material. Where are the gradual swells in “Will I?” that “underscores commonality” and clues us in on “shared terrors” of tomorrow? Why does the counterpoint in “Christmas Bells” register more as noise rather than organized chaos or pre-protest excitement? Where are the different colors, textures, and smells in “Seasons of Love” and “Without You” that become the temporal markers for the changing weather and cyclicality of disease and drug abuse? Instead of imbuing the music with these dynamics, Bartolome’s soundscape is scattered and in permanent winter, narrowing the emotional range, disservicing not only the cast, band, and the audience, but also the material itself.

Despite these, the musical’s best moments still elicit joy and heartbreak. Writer Bruce Weber once said in 2002 that RENT “has always been a talent showcase” and Guevara has assembled a skilled bunch.

Lindayag’s Angel and Bolden’s Collins are the pair with the most chemistry, their saccharine, chaste, and picture perfect relationship eliciting giggles during “I’ll Cover You.” So when Bolden bellows the first notes of “I’ll Cover You (Reprise),” only the heartless remain unmoved. Ian Pangilinan amps up the animatedness of his Mark Cohen, injecting childishness and brewing frustration into a character often played as a passive, two-dimensional observer. Thea Astley’s innocent look and crystalline voice cuts through but her believability as Mimi is hampered by a muted ownership of her body, sexuality, and badassery. Meanwhile, Justine Peña’s Maureen is perpetually on performance mode, with her “Over the Moon” revealing a deeper need for validation in the character, her political disinterest validated in “Take Me Or Leave Me.”

The weakest of the leads is Anthony Rosaldo, whose voice has a powerful come-hither quality of a rockstar but whose presence onstage seems physically, mentally, and emotionally disconnected from the production. Rosaldo slathers on his character’s self-pity without understanding that it comes from a deep yearning for intimacy, rendering sensual numbers such as “Light My Candle” and discoveries in “I Should Tell You” devoid of warmth and wonder. There can’t be a rip in the relationship if there was no connection to repair and much of the second act strains to be beyond mere pantomime. If Roger remains unmoved by love, death, and care, what’s left to awaken him from his solipsism?

RENT’s first act demonstrates how art is used as resistance. Screenplays and posters are burned in the titular number to provide warmth after a power outage (“Rent”). Music serves both as a distraction from disease and a means of spiritual connection for Roger (“One Song Glory”), while stripping and drug use fulfill these functions for Mimi (“Out Tonight”). Performance art becomes a way to combat gentrification (“Over the Moon”) and the bohemian life is depicted as this antidote to raging capitalism (“La Vie Boheme A and B”). But the second act asks: What is the role of art in the face of death?

In his admission of his limits as a filmmaker and a non-HIV positive person, Mark (like Larson in real life) uses his art as a means of memorializing not the movement as an abstract entity but the life of one person. Infante’s set becomes a large canvas onto which Angel’s life is commemorated through projection, his temporary presence swallowing the darkness.

RENT was staged on Broadway at a time when New York had just reached 100,000 cumulative AIDS diagnoses, with over 68,000 of these resulting in deaths. Larson refused to be mere witness to suffering, opting instead to remember not only the tragedies experienced by his community but also sublimating their wishes for an alternative future into his art. In the decision to stage it locally, Guevara allows Larson and his peers to reach across space and time to an unexpected audience 8,491 miles away, suffering from the same loss of life 28 years later. It proves that despite its flaws, RENT’s empathy is larger than its legacy. – Rappler.com

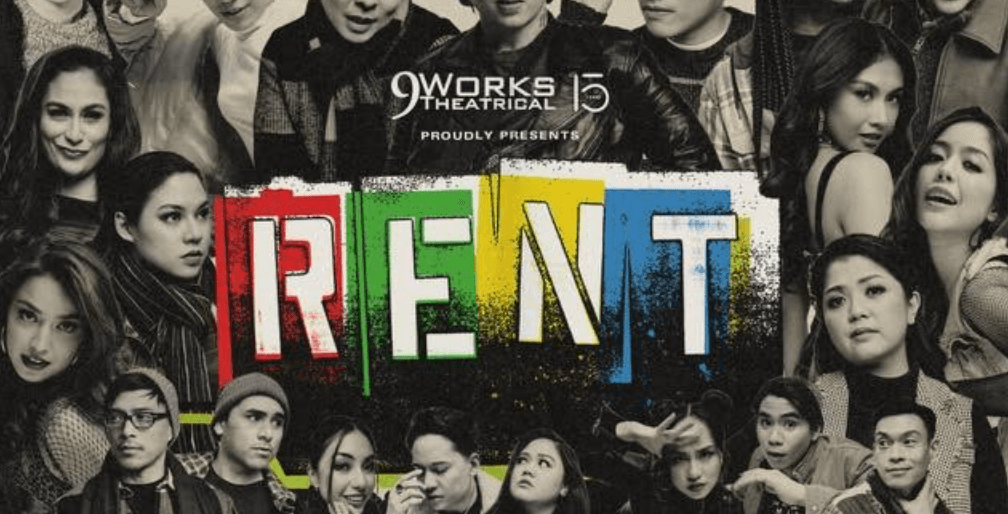

9 Works Theatrical’s RENT runs at the RCBC Plaza Theater until the first week of June 2024.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.