SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Given the state of the economy and the disruption of the pre-pandemic commute, the barriers to watching theater at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (and even mounting a production at such an elite space) have heightened. In the process of writing, I perpetually ask myself: Does this demand to be seen live? What aspects of the show are enhanced when one is in the same physical space as the actors? What details are lost in the shift to the online setting or in viewing a pre-recorded piece? Is any of this worth it?

Virgin Labfest’s “Set B” — Life is Strange Fiction/Hindi Nga?! Weh?: Kataka-taka Trilogy — is described by festival co-director Tess Jamias as a set of “plays that try to turn the famous adage on its head as sometimes, fiction is stranger than life.”

Yet when one looks at the substance of the pieces individually and collectively, one realizes that they all wrestle with the reality of regret in the face of immediate death. Each character struggles with what it means to live a full life and the disappointment of not being able to pursue such dreams — whether because of war or work or family or something else. It is a set that holds up a mirror to its audience and asks how they want to live their life, who they truly value in this world, and what it means to move forward despite such debilitating sorrow.

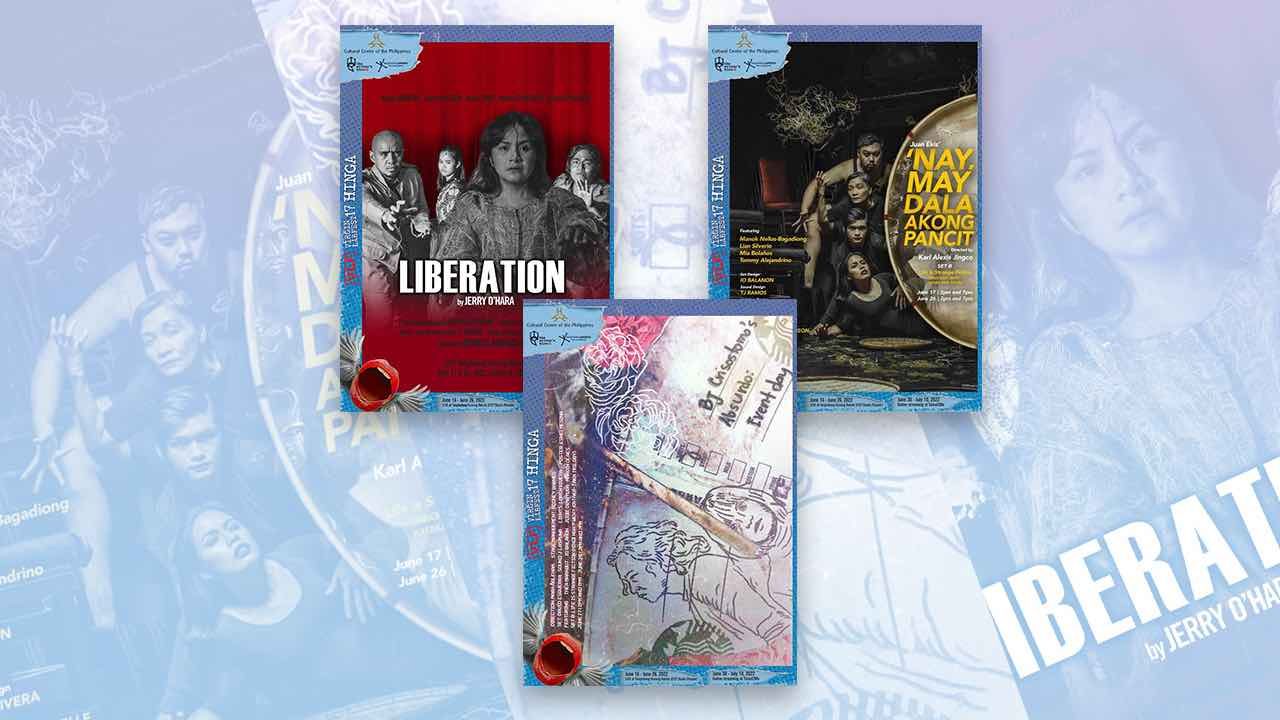

Liberation (written by Jerry O’Hara, directed by Dennis Marasigan)

One can argue that Liberation must be looked at metaphorically. It can be seen as a dissection of the male psyche — each soldier a physical manifestation of the id, ego, and superego that is at war with itself, constantly negotiating power away from one another. One can also argue that it is a story of entrapment and emasculation — of how men participate in a cycle of violence that they continue to perpetuate through blind obedience and desire for revenge. One may also look at it from a nationalist perspective — the woman symbolic of the Philippines, the soldiers of the colonial systems that permeate until the present, whose violations destroy indiscriminately.

But one cannot help but wonder why, given playwright Jerry O’Hara and director Dennis Marasigan’s commitment to telling missing narratives in Philippine history, they would center Liberation on three Japanese soldiers — none of whom look nor speak Japanese convincingly. Historical distortion by the Japanese forces, especially brought to light by the recent assassination of former prime minister Shinzo Abe, has been a dominant narrative in world history. Why does it ask us to empathize with our colonizers? What can we stand to gain from such a story that attempts to humanize the morally reprehensible characters such as Haruto (Chrome Cosio) by exposing that he is a victim himself?

But more importantly, what does this have to do with the woman? Why does her rape — its inevitability dangling over the audience like a sharpened guillotine — bookend the narrative, especially when it is ultimately inconsequential to the story? Are there not already thousands of such metaphors already in existence — some of which are in VLF this year alongside it — in film, TV, theater, art, and literature?

In the process of depicting and discussing these historical atrocities, it becomes increasingly unclear who the material seeks to liberate in the first place. These questions remain unanswered because Liberation fails to imagine beyond history. Instead, it only lazily depicts reality.

Absurdo: Event Day (written by BJ Crisostomo, directed by Mara Agleham)

The last two years have seen a major shift in the conversation about work. From the instability of freelance work and the gig economy to the issues with work-from-home and on-site jobs, the dream of a “work-life balance” has slowly eroded, replaced by the need to hustle before being struck by unemployment or even the possible recession. One wonders why, given the value of such discussion in shaping the country’s survival and its ever-present mark on the cultural zeitgeist, a space was not made for Absurdo: Event Day in the Revisited section of the festival.

Written by BJ Crisostomo and directed by Mara Agleham, Event Day follows two project coordinators, Aly (Charm Aranton, replacing Thea Marabut last minute) and Rain (Io Balanon), organizing an End-of-the-World party. Forced to be multi-hyphenates by the demands of their jobs, Aly and Rain find themselves perpetually sacrificing their freedoms for their abusive and insatiable bosses. Balanon’s charm matched with Aranton’s expressive face and physical comedy are a winning combination, their chemistry keeping the text afloat, even in scenes that feel overwritten.

While Judie Dimayuga offers a jolt of humor through her last minute appearance, one cannot help but feel disappointed at the decision to physicalize the boss — who appears to be every bit as petty and unreasonable as imagined, decreasing the power of the piece. One cannot help but wish the text depicts her as more uptight and seemingly benevolent — a quiet contrast to the talk-heavy duo like Senator Juancho Valderrama in The Kundiman Party — to underscore the difficulty of quitting and to make the rebellion against her that much sweeter.

The comedy and tragedy comes from the attempts at justifying the inhumane conditions they are subjected to — dismissing everything from complaints about minimum wage and losing time with their families to their inability to disconnect from their phones and the absurd demands of their clients. Capitalism co-opts these doomsday scenarios for profit — as seen in the numerous posters littering David Esguerra’s set design. Absurdo: Event Day creates a microcosm of how such death-dealing systems have woven themselves so inextricably into our lives that it is near impossible for us to imagine ourselves and each other without them.

The scariest part? Before the play has a chance to imagine a world beyond, it ends.

Nay, May Dala Akong Pancit (written by Juan Ekis, directed by Karl Alexis Jingco)

If you would have told me that one of the best VLF plays this year uses pancit as a weapon for homicide, I don’t know if I would have believed you.

Yet within the first few minutes of Nay, May Dala Akong Pancit, it becomes clear what ride we are in for. Playing with the soap opera trope, Bunso (Manok Nellas-Bagadiong) tells her brother (Lian Silverio) that they are stuck in a metaphysical loop and that bringing home pancit causes their mother (Mia Bolaños) to die. Despite their best efforts, the two consistently find pancit in their homes, often unveiled by Tommy Alejandrino’s myriad of secondary characters — delivered through Grab, cooked by their mother, vomited by a possessed demon, brought in by a holdaper, or even raining from the skies after a multiverse of madness.

What is most gripping about Pancit is its playfulness in form. From its beginnings as a simple soap opera snippet, it grows increasingly complex and absurd — transforming into a musical, a horror, and even an improv session where the characters break the fourth wall, asking the audience for help getting out of this mess. These changes — made possible by TJ Ramos’ sound design, Loren Rivera’s lighting, and Io Balanon’s set — keep the audience engaged and searching for where the pancit could come from next, trained like Pavlovian dogs salivating at the ring of a bell.

Stories have played extensively with this trope, opting for different solutions each time. In Groundhog Day, the solution is self-improvement. In Russian Doll, it is helping others out of their self-destructive labyrinth. In Palm Springs, the exit is a physical one, requiring understanding of quantum mechanics. In Waiting for Godot, the absurdity has no exit and is only assuaged by companionship. Midway through the play, one wonders: what possible ending can Pancit come up with that is sensible yet surprising? Yet it does, executed in a manner so simple and heartbreaking that one cannot help but give into the emotions.

It’s easy to see the loop and its iterations as a gimmick, but these formal experimentations resonate much more due to the pandemic — highlighting how people now wrestle with the certainty of death, capturing the feeling of repetition and stuckness during lockdowns, and excavating the value of family and honesty. Such a comedic miracle could have only come from a highly collaborative environment, cultivated by playwright Juan Ekis and director Karl Alexi Jingco with the entire team.

Nay, May Dala Akong Pancit is work that demands to be seen in person — in a room where laughter can be shared, tears can be shed, and one can exclaim:

“Thank God, theater is back. Thank God, I am alive.” – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.