SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

READ: Part 1: In a Philippine village, pangolin hunting happens under local officials’ watch

PALAWAN, Philippines – On September 27, law enforcement authorities seized 38 sacks containing 1151.89 kilos of Philippine pangolin (Manis culionensis) scales in an abandoned house in Puerto Princesa City, Palawan.

The pangolin scales with supposed medicinal properties, alongside other confiscated wildlife derivatives, were believed to be destined for the black market in China where their collected estimated value was P500 million. It is considered to be the biggest anti-wildlife trade operation in Palawan to date. Unfortunately, the authorities failed to capture the storehouse owner, Filipino businessman Gary Abriol, who wasn’t there during the operation.

“According to our operatives, he’s [been] involved in wildlife trafficking ever since,” said Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Penetrante, Armed Forces of the Philippines Western Command spokesperson, in a press conference. Now a subject of a manhunt, Abriol was alleged to be using his technology-related business as a front for his illegal wildife trafficking activities.

Abriol has also been linked to a local Chinese businessman, Tony Sy, who had been involved in a wildlife smuggling case in 2014, according to a Palawan News report. Sy’s case, however, was reportedly dismissed during the preliminary investigation stage, but now he is under military custody for a case on illegal online gambling operations involving hundreds of Chinese workers he allegedly smuggled into Palawan.

There’s one thing, authorities alleged, that Abriol and Sy may have had in common: they probably had been financing the wildlife poaching and trading in Palawan, pushing pangolin and other native species to the edge of extinction. (READ: Trafficked to extinction: Indonesia and Philippines)

How pangolin traffickers operate

Local wildlife trade financers connected to international wildlife trade syndicates are already embedded in the province, said Nino Estoya, operations director of the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development Staff (PCSDS), a government agency mandated to enforce the Philippine Wildlife Act in Palawan.

Past trend showed the nationality commonly involved in local pangolin trading was Taiwanese. “But, now, the dominant nationality is Chinese,” the PCSDS operations director told Rappler.

Philippine pangolins are not locally sold for pets, unlike other wildlife like birds. For domestic pet trade, Filipinos are on top of the game.

“Pangolins fall under the international trade which heavily involves foreign nationals from China, Hong Kong, and other countries,” where this species is consumed on a commercial scale despite the international trade ban imposed to save this most heavily trafficked mammal, he explained.

Estoya said these organized international wildlife syndicates have local financiers who are responsible for consolidating pangolins and other wildlife which are smuggled out of the province. Under the financiers who are usually local businessmen, there are middlemen assigned to towns to buy and collect the pangolins from the poachers living in poverty-stricken communities.

Lawyer Edward Lorenzo, wildlife crime prevention specialist of the USAID Protect Wildlife project, said maritime transport plays a huge role in wildlife trafficking that increasingly targets pangolins, as they are transported by sea through pump boats or fishing vessels.

“Palawan is one of the major hotspots in the Philippines for wildlife poaching and trafficking. It is both a gathering area and a transshipment site,” Lorenzo said in a wildlife law enforcement summit held recently in Coron, one of the island towns that make up the Calamianes or Calamian Group of Islands in the province’s northernmost part.

“Increasingly, the maritime domain has been used in transporting wildlife because it’s difficult to guard,” Lorenzo added. “So, most of the transshipment points are not airports but seaports.”

Philippine National Police maritime director Police Brigadier General R’win Pagkalinawan said they currently don’t have high-speed boats in northern Palawan that can keep up with the wildlife smugglers’ boats traversing high seas within Calamianes. What they have now are one rubber boat in Coron and another one in El Nido for northern Palawan.

“But those rubber boats cannot chase smugglers in boats because they move faster. So I need high-speed tactical water crafts here,” Pagkalinawan told Rappler.

The maritime police chief said that while they are awaiting the delivery of 22 high-speed tactical boats by March 2020 – one of which he intends to deploy in Coron – they are partnering with resort owners who lend them speed boats to carry out the operations.

Meanwhile, there are only 11 maritime police stationed in Coron, but Pagkalinawan said this number is not enough to combat wildlife crime on Calamian seas. “No, it’s not [sufficient]. The ideal is there should be at least a marine police officer assigned to every municipal police station,” he added.

Like in Abriol’s modus, pangolin scales and other wildlife byproducts are gathered from all over the province and kept in a storehouse until such time circumstances allow for their shipment.

“They (wildlife trafficking financers) will store the wildlife derivatives in a stockroom before shipping them out of the province through regular ports like in Puerto Princesa City, El Nido, and Coron towns,” Estoya observed. To evade detection, they mislabel or misdeclare, and mix the illicit wildlife products with legal ones as modes of concealment.

Wildlife smugglers employ a different approach if they are to transport live pangolins and other wildlife out of the country.

They exit the country via backdoor in Bataraza and Balabac towns in southern Palawan where the presence of law enforcement groups needs beefing up.

“The collected wildlife from all over the province are transferred to a vessel that departs the country and traverses West Philippine Sea,” Estoya added.

In the Calamianes that covers Busuanga and Culion Islands, the said wildlife and its byproducts, if not transferred to the backdoor at the province’s southern tip, are transported directly to Mindoro or Batangas provinces – other transshipment points.

Wherever their points of exit in the province are, they always end up in one destination: China.

With the increasing reliance on fishing vessels to transport pangolins and other wildlife from Palawan, what can be done to address security issues on transshipment is to “shift the orientation of LGU Bantay Dagat from just fisheries but to address security issues on transshipment,” Lorenzo said.

The wildlife crime prevention specialist also added that “there should be increased monitoring of ports, especially those which allow for direct international access, of which there are several in Southern Palawan. For the informal ports all over Palawan, these should be monitored as well by local officials for the IWT (illegal wildlife trade).”

Busting organized wildlife crime groups

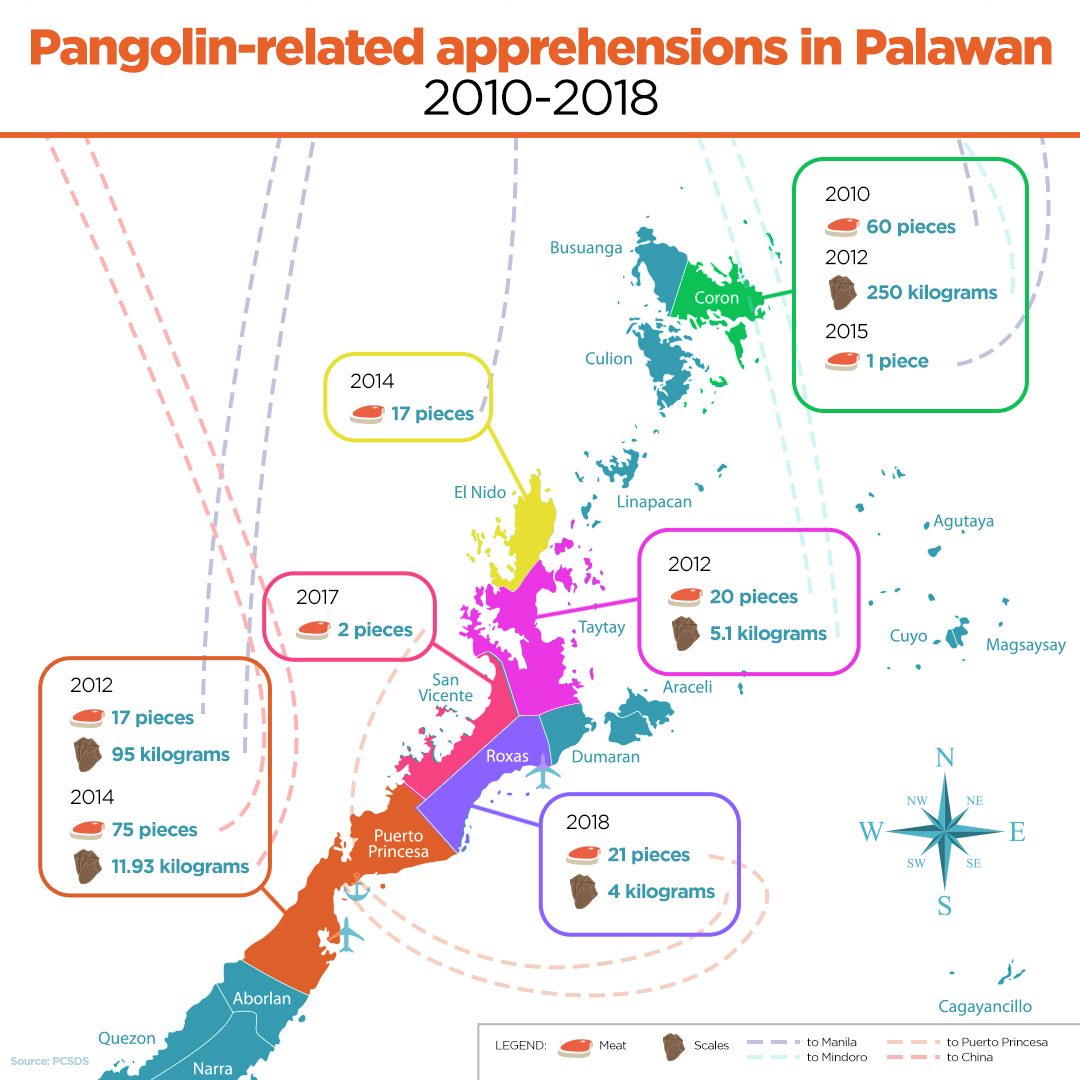

From 2010 to 2018, PCSDS data showed that 213 pieces of pangolin meat and 366.03 kilograms of scales had been seized, while 20 live pangolins had been rescued and released back to the wild. On top of the said figures were the 1151.89 kilos of pangolin scales netted in a single apprehension last September 2019, outnumbering confiscations of its kind in the past 8 years.

During the same period, law enforcers arrested 33 persons, mostly poachers and middlemen, for possessing and transporting live pangolins and their derivatives. While this can be considered a cause for celebration, catching pangolin traffickers at the base of the transnational organized wildlife crime syndicate structure is not enough.

“Those who are usually arrested are the catchers, the gatherers. What’s the problem? We don’t move one or two steps higher. You have to look at it as a syndicated crime. Who’s at the top?”

Lorenzo asked rhetorically: “They have financers. Who are these people? That’s what we need to find out.”

Are Abriol and Sy, who had repeatedly been implicated in wildlife trafficking in the province, also acting as pangolin trade financers? Who are the people above them? Will Abriol’s arrest lead to the busting of the transnational organized wildlife crime syndicate to which they might be affiliated with?

These need further investigations, and enforcement authorities refused to comment about the background of the two as the criminal cases against them have already been filed with the court.

In going after wildlife traffickers, Lorenzo said enforcement agencies can utilize other laws, including cybertrafficking and money laundering laws. “These may give added investigatory avenues to track traffickers at least two levels higher, and add to penalties for violators,” he added.

Lorenzo also said “investigations should not end at the apprehension phase but should also engage in link and event analysis due to the increasing trend of syndicates being involved in timber and wildlife trafficking.”

Underfunded, understaffed enforcement units

Among the issues plaguing the PCSDS are the lack of funds and personnel to effectively carry out wildlife enforcement operations all over Palawan, the Philippines’ largest province with a 1.5 million-hectare land area and a 2,000-kilometer coastline encompassing 1,768 islands.

In the last 5 years, the PCSDS’ regulation and enforcement division received the following budget allocations: P3,934,000 in 2015; P4,550,000 in 2016; P13,950,000 in 2017; P11,694,000 in 2018; and P14,460,000 in 2019.

While the budget is increasing year after year, it’s still not enough to cover all the native species the agency needs to protect. Considered as the Philippines’ last ecological frontier, Palawan cradles more than 38% of the country’s total wildlife species. Out of 58 terrestrial mammal species the province hosts, 16 are restricted only to this area – including the Palawan pangolin.

“With so many government agencies that need funding, we always have to grapple with the budget. If you don’t nudge the national government, you won’t get budget. That’s the reality considering the countless concerns it needs to address,” environmental lawyer Adelina Villena, PCSDS deputy executive director, told Rappler in a separate interview.

PCSDS is an agency under the Department of Environment and Natural Resources. Currently, it has no regular enforcers, only job order ones, numbering around 8, who serve as “strikers” whenever they are needed in apprehensions in the field. There are also 20 wildlife traffic monitoring officers assigned in strategic airports and seaports located in 15 towns to intercept wildlife smugglers.

“Forging partnerships is one of our ways to move forward because the government has no big funds for the enforcement,” Villena said.

To make a dent in pangolin trafficking, the PCSDS enforcement team has engaged in surveillance and tapped the intelligence community, including the Philippines’ police, navy, and army. Despite this synergy, Estoya said environmental law enforcement efforts remained “uncoordinated” as the communities on the frontlines were not involved in the fight against wildlife traffickers.

“Because of that, our intelligence system is weak,” he admitted.

The USAID Protect Wildlife provided a series of capacity building workshops for PCSDS and its partner organizations to help combat wildlife trafficking in Palawan, a biodiversity hotspot. Currently, this foreign-funded project is also assisting the said government agency in developing a digital public reporting system, enabling communities to alert enforcement authorities on wildlife poaching and trafficking incidents.

Expected to be operational by the end of 2020, this online system with intelligence and predictive capabilities will be managed by the PCSD Committee on Security and Safety, headed by the Armed Forces of the Philippines Western Command chief. With the completion of this system comes the activation of the Palawan Environmental Enforcement Network that includes response teams from the provincial level down to the barangay level.

Foreign assistance

As the PCSDS enforcement team is underfunded, it needs to rely on foreign assistance. This dire situation only underscores that the national government is not putting a prime on wildlife enforcement to conserve nearly extinct species like the fPhilippine pangolin, which is nowhere to be found in the world except in Palawan.

“The way enforcement is being done in this country is it’s very limited to only a few people. And then the enforcement efforts are not well-funded,” environmental lawyer Grizelda Anda, executive director of the Palawan-based Environmental Legal Assistance Center (ELAC), told Rappler in a separate interview.

“It does not appear to be a priority of the national government.”

Palawan towns created their enforcement units to complement the law enforcement agencies, but most, if not all of these units are still in their developing stages and don’t solely focus on wildlife law enforcement.

They don’t even receive enough funding from their respective municipal governments to effectively carry out their task of going after wildlife law violators operating within their jurisdiction.

In Culion, an island town part of the Calamianes where the Palawan pangolin got its scientific name, its enforcement unit, Bantay Culion, was only created in November 2018. Bantay Culion chief Alejandrino Abrina Jr said combatting pangolin poaching and smuggling weren’t priorities of the past municipal governments, and it’s only now that these issues have been given attention.

“In the 1990s to 2000s, the hunting for trade was really rampant. People here didn’t foresee it would someday become endangered,” Abrina told Rappler, referring to the Philippine pangolin that has been designated as the Culion’s flagship species.

Abrina, however, is hired as a job order employee and has no personnel under him. Because of this, implementing the wildlife act remains a challenge for an island town with multiple possible exit points and poor law enforcement presence.

Anda said wildlife enforcement is “a critical area of governance” that requires “regular funding and regular support to the enforcers.”

This means enforcers have to be employed as regular staff with benefits being enjoyed by typical government employees, plus life and health insurances to compensate for their dangerous job. To perform better, enforcers should also have basic enforcement paraphernalia, such as but not limited to uniforms and vehicles.

Had the national and local governments integrated wildlife enforcement into their development plans, they wouldn’t have depended on external forces for technical and logistical support to combat wildlife trafficking that increasingly targets pangolins.

“The enforcement mechanism must be institutionalized, meaning it is part of the government’s development plan every year,” Anda said. “If it’s not integrated, you’ll have to depend on external forces like the USAID to fund it. No. It should be a government commitment, and that to me is the biggest problem. We are not able to integrate wildlife conservation into our overall development plan.”

The ELAC chief claimed that the national and local governments do not prioritize wildlife conservation and law enforcement because “it doesn’t give them money,” as opposed to infrastructure development that always gets more budget.

“At the end of the day, it’s basically a perspective of the government on how they look at wildlife. They have to integrate wildlife enforcement and wildlife conservation with the overall goal of sustainable development in a particular municipality, province, or the whole country,” Anda added. – Rappler.com

This series is part of The Pangolin Reports, a news initiative by the Global Environmental Reporting Collective to investigate the illegal wildlife trade of pangolins across Asia, Africa and Europe.

TOP PHOTO: This file photo shows a Palawan pangolin rolled up into a ball. File photo courtesy of Emerson Y. Sy/PCTAR

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.