SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Why would anyone think of hiding around 100 rare birds in a mausoleum in the Manila North Cemetery?

This was what Police Superintendent John Guyguyon thought as he facilitated the raid of an illegal wildlife trader’s lair back in September 2014.

A Caloocan barangay kagawad (village councilor) named Jerry Juan was arrested that day for the illegal possession and sale of rare birds – many of them endangered – kept in two mausoleums in the cemetery.

Guyguyon and 15 other operatives of the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG) found cages of birds perched on top of crypts. The total value of the haul was estimated at P450,000 ($10,200) – not the biggest of the year but surprising due to the strategy employed by the suspect.

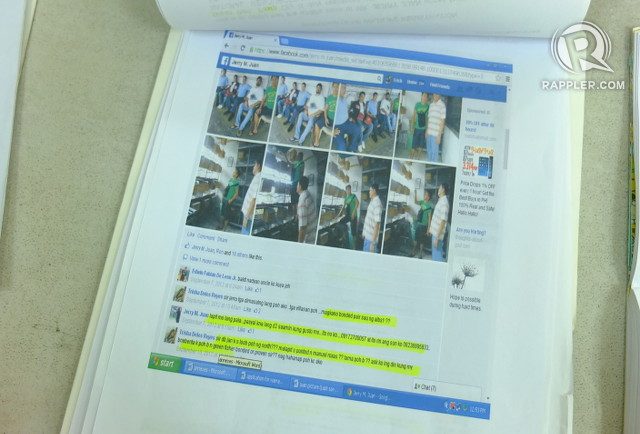

Juan would take photos of the birds and post them on Facebook. Interested buyers would then comment and the transaction itself would be facilitated in private.

Guyguyon’s colleagues in the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) found out where Juan was keeping the birds through Facebook. A careless comment, a distinct photo – the straws environmental cops use to nab elusive illegal wildlife traders.

That day, Guyguyon, and the rest of CIDG and DENR agents saved Philippine cockatoos and African Grey Parrots – classified as endangered.

The Philippine cockatoo, worth around P60,000 ($1,300) each in the illegal wildlife market, are critically endangered and are found only in the Philippines – specifically in Rasa Island in Palawan.

Guyguyon is one of the few government enforcers tapped to fight the illegal wildlife trade. In 2014, officers like him were responsible for 19 confiscations worth P7.2 million ($163,000).

Dangerous job

Guyguyon leads a CIDG team often tapped by the DENR to provide assistance during raids on illegal wildlife traders.

DENR operatives are not allowed to use firearms, making it dangerous for them to go after traders.

“[The suspects] sometimes fight it out. They have firearms. But we go in full force so that the element of surprise is there to prevent them from any funny business,” Guyguyon told Rappler.

His team has to be extra careful before infiltrating a trader’s location. They coordinate with local government officials and monitor the area first.

Their worst fear is if a trader suspects their presence and decides to kill the animals to hide their guilt.

But in other cases, the traders pretend the animals are just their pets. But you can identify animals meant to be sold by their large numbers, said Guyguyon.

Another common modus operandi of traders is to hide under the business of selling legitimate pet animals.

“In Cartimar, for example, they have stores but they don’t display the illegal animals. When you’re there, they will just tell you, ‘Meron din kaming ganito (We also have this),’ but the animals are hidden in their houses,” said Guyguyon.

The animals themselves endanger the lives of the cops. That’s why the operatives avoid conducting raids at night.

In one operation, the team had to confiscate poisonous snakes and crocodiles, hidden in plastic drawers. The haul, composed mostly of reptiles and amphibians, was valued at P4 million ($90,500).

The wildlife often come from the Visayas, Mindanao, or Palawan, said Guyguyon. Some come from China or other parts of Asia. That’s why some raids take place in ports or at sea – on boats carrying undeclared cargo.

The road to an arrest

In the verdant grounds of the DENR’s Biodiversity Management Bureau, Rodel* clutches one of his many cellular phones. This one contains the numbers of several suspected illegal wildlife traders and a few death threats.

Rodel is a DENR legal officer trained to build cases against suspected traders.

He was the one who developed the case against Juan, based on a Facebook comment he discovered, made by a prospective buyer naming the location of Juan’s “shop.”

He and a colleague searched the North Cemetery for the mausoleums, discreetly took pictures of the structures (even posing as devotees of a celebrity buried nearby), and interviewed cemetery caretakers.

It wasn’t all that difficult to find the mausoleums. Rodel could hear the entrapped birds chirping even from far away, he told Rappler.

Two months of case-building allowed them to apply for a search warrant. Thirty minutes before the raid, Rodel was in a Manila regional court, waiting for the release of the search warrant.

Not all operations are as successful as the North Cemetery one.

Rodel once posed as a buyer and met with an illegal trader. The trader was smart. He instructed Rodel to get into a car which would take him to an undisclosed location.

“[The traders] are always one step or two steps ahead of us.”

– Rodel*, DENR Wildlife Officer

Rodel had his “budol budol” money with him – bundles of yellow paper cut in the shape of cash. Only the P500 on top was real. He was ready to show it to the trader to show he was ready to pay.

But once they got to the location – a gas station – the car sped off. Rodel believes that somehow, his cover was blown. The trader sped off with two Philippine hornbills – a critically-endangered species.

Eye-balls and meet-ups are among the dangerous components of building a case against a trader.

Traders often do not have government papers that would identify them and their address. So operatives have to dig deeper and even meet up with them to get more accurate information to present to court.

The court only issues a search warrant when it is satisfied with the presented evidence.

Two steps ahead

In recent years, an increasing number of illegal wildlife transactions take place on the Internet, where identities are easily hidden and paper trails are non-existent.

“They are always one step or two steps ahead of us,” said Rodel.

Rodel keeps a fake Facebook account which he uses to “transact” with several traders, waiting for them to slip and provide the information he needs.

But even after they nab the suspects, operatives like Rodel are still vulnerable.

Traders, often “well connected,” tend to file numerous lawsuits against government agents for grievances like illegal arrest or qualified theft.

“Majority [of the cases] will be dismissed but the ultimate goal is to harass a wildlife enforcer hanggang maubos ‘yung pera namin, manghina kami (until we have no more money, until we ger exhausted),” he said.

That’s why Rodel, who thankfully is a lawyer, is very careful in building cases and enforcing search warrants.

The raids are conducted with witnesses and all evidence, including photos, are accompanied by affidavits. The inventory of confiscated wildlife are done under oath.

You can count the number of specially-trained operatives like Rodel with one hand. The team is small, the problem large – even transboundary – in nature.

It is a thankless job, but someone needs to protect endangered animals, said Rodel.

“Just a few more deaths and you might never see animals like these again. Maybe the next generation never will. So it’s very fulfilling when we are able to save some of them.”

For Guyguyon, his job is about saving national treasures.

“This is a symbol of our country and yet we destroy them. We will be known as Filipinos who don’t care,” he said.

The victims themselves, the endangered animals, are unable to show emotion, unlike human victims of other crimes.

But operatives like Rodel and Guyguyon like to think that nature has her own way of saying thank you.

Guyguyon said: “I make it a point to go home to my province of Ifugao every weekend. I like to hear the birds in our backyard in the morning. You feel rejuvenated, refreshed. Then you come here again and do the work.” – Rappler.com

*Name has been changed due to the highly sensitive nature of his work.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.