SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Gerlie Menchie Alpajora was sleeping beside her two sons when she was shot dead inside their home in Camarines Sur 5 years ago.

According to reports, she was killed just after her report to local authorities led to the arrest of people involved in illegal fishing in their locality.

An anti-illegal fishing advocate, Alpajora served as the secretary of Sagñay Tuna Fishers Association, a community-based group that assists law enforcers in monitoring and reporting illegal fishing activities in Camarines Sur

Alpajora’s case remains unresolved to this day, but her murder led to a remarkable collaboration among activist community enforcers, the police, and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs), according to the Environmental Justice Atlas (EJA).

The EJA said this collaboration resulted in a 300% increase in arrests of fishing criminals in 2015.

Monitoring and reporting illegal fishers come with danger – from braving rough seas to death threats. But according to the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), illegal, unregulated, and unreported (IUU) fishing is the top reason for the declining conditions of fisheries and the marine environment.

Quantifying the resulting losses due to IUU fishing is key to knowing the exact extent of the problem in the country.

How much is PH losing?

Did you know that the amount the country loses from IUU fishing is enough to feed around 281 million Filipinos for an entire year?

This is according to USAID, which has partnered with the Philippines’ Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) to address the IUU fishing problems in the country.

The Philippines loses nearly P5 trillion due to IUU fishing and post-harvest losses, according to a recent report citing a study by Rhodora Azanza, professor emeritus at the Marine Science Institute of the University of the Philippines. This amount is merely a rough estimate because there’s no exact way to measure the impact of IUU fishing, according to USAID.

While that is true with respect to foreign vessels that encroach on Philippine waters, the government now has a way to deter and prevent the impact of IUU fishing on municipal waters.

Fisheries Administrative Order (FAO) No. 266 sets the rules for implementing the vessel monitoring measures requirement under Republic Act No. 10654, which amends the Fisheries Code of 1998.

Signed just this October by the Department of Agriculture (DA), this long-overdue revision of guidelines under FAO No. 260 was welcomed by civil organizations and local governments.

FAO No. 260, issued in 2018, covered only vessels heavier than 30 gross tons – those that usually catch straddling stocks and migratory fish.

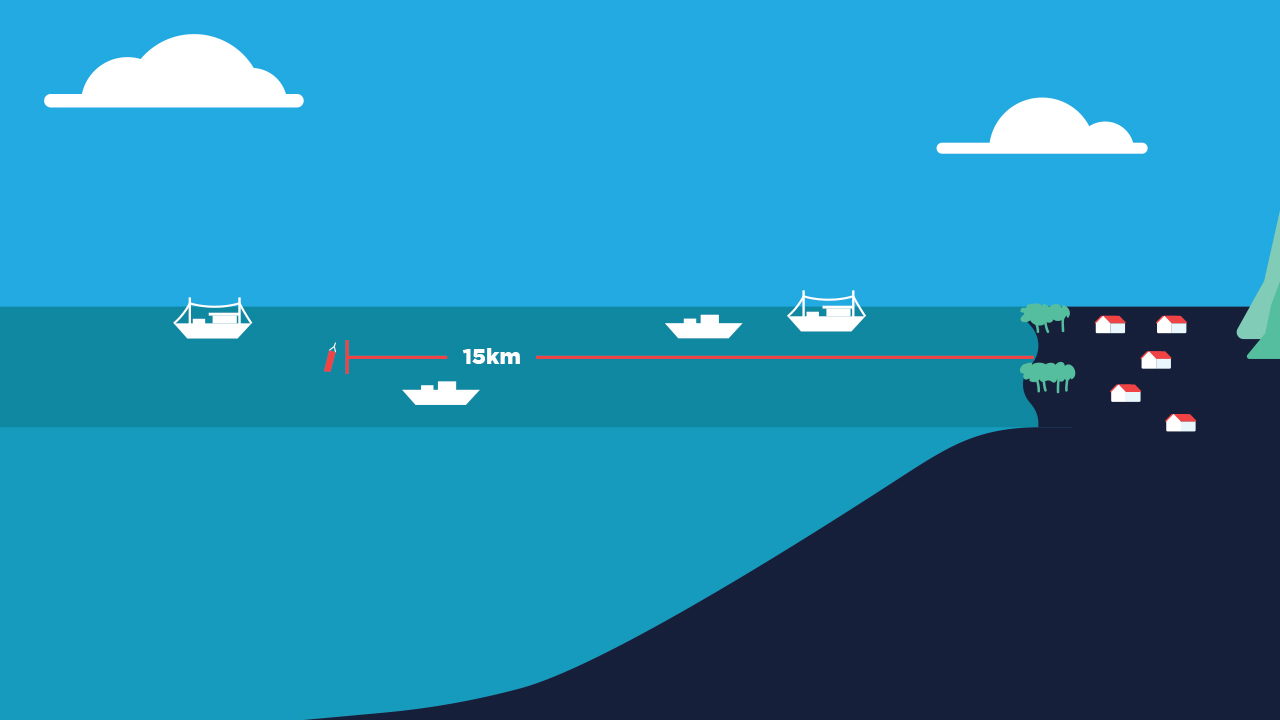

“We welcome the issuance of the guideline for vessel monitoring mechanism that covers all commercial fishing vessels more than 3 gross tons [which may be allowed in municipal waters at a minimum distance of 10.1 kilometers from the shore],” said Dinna Umengan, coordinator of the Pangisda Natin Gawin Tama or PANAGAT, an umbrella organization of NGOs working with fisherfolk for ocean and environment conservation.

This version is now consistent with the provisions of Republic Act No. 10654, or the Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated Fishing Enforcement Act of 2015, which requires all Philippine-flagged fishing vessels regardless of fishing area and final destination to have a monitoring, control, and surveillance system. Its aim? To “prevent, deter, and eliminate” IUU fishing in the country.

“We believe that this can help curb illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing, especially the encroachment of commercial fishing vessels within the 15-kilometer municipal waters. This is a big win for coastal local government units and fishing communities, and a contribution towards the modernization path of the Philippine fisheries industry,” Umengan added.

Importance of monitoring

According to Oceana Philippines, vessel monitoring systems are used to monitor and track the position, course, and speed of fishing vessels. They can establish whether these vessels are violating fisheries laws, informing fisheries managers how, where, and when a certain resource is being exploited.

Back in September, the League of Municipalities of the Philippines’ (LMP) Romblon chapter reiterated its call for the DA to fast-track guidelines for commercial vessel monitoring measures. LMP, the formal organization of all municipalities in the Philippines, believes that this will help fight illegal fishing within municipal waters.

This delay in implementation adversely affects the country’s food security, as well as the social well-being of those employed in capture fisheries – a total of 1.7 million Filipinos, according to BFAR’s report on the 2019 state of Philippine fisheries and strategic initiatives.

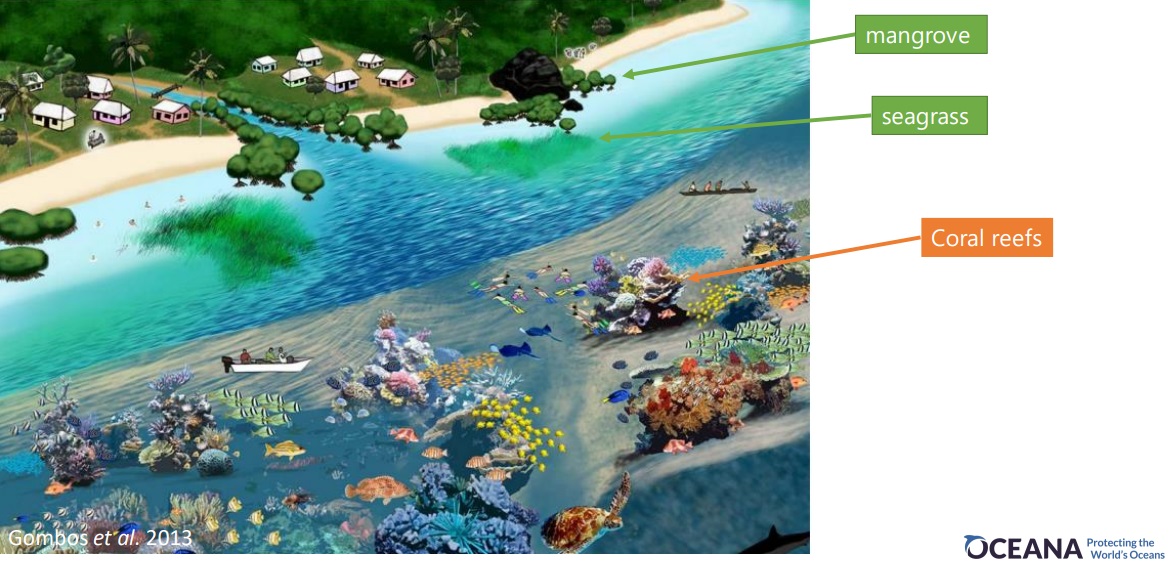

Destructive and illegal fishing methods in prohibited zones degrade important marine ecosystems usually found within municipal waters.

Municipal waters – or waters 15 kilometers from the coastline – are important because these are highly productive areas.

Not only are these critical habitats and hosts to carbon sequesters like mangroves and seagrass beds, they are also usually more full of life than deeper waters beyond because abundant nutrients from rivers and sunlight reach these shallow waters.

Sunlight is needed for the growth of phytoplankton, a primary food for small and larger fish, including sardines. Municipal waters are also where coastal upwelling happens, when surface winds pull the nutrients from deeper waters for phytoplanktons.

That’s why marine protected areas are proven to help increase the size, density, weight, and richness of marine species. If municipal waters are fully protected, the adjacent areas (i.e., fishing grounds for commercial fishing vessels) will benefit too from a spillover effect, a known consequence of marine protected areas, which happens when sea animals leave the protected area for fishable waters.

Enforcement

But it is not only illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing that can undermine efforts to improve the management of the country’s fisheries resources. Bribery, inaction, and significant court delays compound this critical fisheries issue.

Even in areas with strong community enforcement practices, violators can still escape prosecution.

In Romblon, Romblon, the provincial prosecutor allegedly let go of a commercial fishing vessel that was impounded for violating the Philippine Fisheries Code via a motion for relief.

According to an affidavit signed by Police Senior Master Sergeant Gerald Faigmani from the Romblon municipal police which was filed with the provincial prosecutor’s office on November 22, 2019, one of the fishing boats of Jelka 5 Star Fishing Corporation was reportedly caught using superlights and active gear inside municipal waters.

This was in violation of Sections 86, 95, and 98 of Republic Act No. 10654. The law bans the use of active fishing gear such as, but not limited to, trawl, purse seines, Danish seines, paaling fishing and drift gill net, and a fishing light attractor.

According to the same affidavit, Jelka’s license was already expired. While a respondent may file a motion to release his or her impounded Philippine-flagged fishing vessel at any time during the proceedings, the BFAR Rules of Procedure for Adjudication of Fisheries Law Cases, however, provide that no motion to release shall be granted to an unregistered and/or unlicensed fishing vessel. Yet on December 23, 2019, the prosecutor’s office allowed the vessel to go via a motion for release.

The vessel also left with the main evidence onboard, according to court documents obtained by Rappler.

Fisherfolk, NGOs, and concerned individuals rallied at the prosecutor’s office to demand the recall of the evidence, according to a witness who asked not to be named. This case and another fishing violation incident by Reina Mercedes Fishing Corporation have yet to move, however.

“I felt like our efforts to catch these violators went futile,” said Job Martinez, a sea warden from Barangay Agpanabat in Romblon. A sea warden is tasked to keep an eye on any illegal activities in municipal waters.

As the town’s lead sea warden, Martinez coordinates with 75 other sea wardens from Romblon’s 31 barangays, as well as with inter-agency enforcers. He earns P10,000 a month from the local government unit (LGU).

Working with communities

In the province of Romblon, the monitoring of municipal waters is a community effort.

“The church and the provincial government let us use their speed boats for seaborne operations, including a high-powered personal speed boat of a representative of Romblon that can cut a two-hour trip to 30 minutes,” said Romblon Mayor Gerard Montojo.

In March, Banton and other nearby island towns coordinated with the Romblon Diocesan Social Action Center (RDSAC) to catch a violator. Municipal fisherfolk send a text message to Martinez, if not to Montojo, every time an “illegalista” (local term for violator) is spotted.

Martinez said that this coordinated enforcement on the ground helps discourage, if not totally deters, intruders. Fr Rick Magro III of the RDSAC said that the fisherfolk are now more confident about having a good catch, unlike before when they were not motivated to participate in the RDSAC’s livelihood program because of their dwindling fish catch.

The amended Fisheries Code requires BFAR to create a Fisheries Management Fund under a special account in any government financial institution, where fines and penalties collected from violations go.

The fund can be used for monitoring technology, operating costs, research and development, capacity development of enforcers, scholarship grants for the children of fisherfolk, livelihood programs, fisherfolk assistance in the form of shared facilities, and payment for litigation expenses as well as medical expenses for injury or indemnity for death of law enforcement officers.

This means that every missed enforcement is a big loss for BFAR personnel, deputized law enforcement agencies, volunteers, government researchers, and stakeholders like law-abiding vessel operators and municipal fisherfolk and their families.

Missed enforcement can also happen because of areglo, an intervention or compromise that frees a violator from sanctions, or reduces his culpability in exchange for a “gift” such as cash.

According to Karagatan Patrol, an online platform for reporting illegal fishing activities, an areglo can happen at any stage of enforcement – whether at pre-boarding, boarding, or post-boarding.

Conducting joint operations with another unit, or publicizing the operation via social media, if signal allows, can help prevent areglo, according to Karagatan Patrol. The group also encourages the public to report all forms of areglo.

According to the John J. Carroll Institute on Church and Social Issues and international NGO Rare, strong LGU support for community sea wardens, as well as strengthened collaboration efforts among inter-agency enforcers, can increase environmental protection measures for municipal waters.

While there are still unresolved cases related to IUU fishing like Alpajora’s murder, there have been legal successes, too. In Davao Region, for example, a commercial fishing vessel’s license was permanently terminated last February for repeatedly violating fishing laws.

The EJA attributed this achievement to continued activist pressure, and expected this would “lead to a massive legislative crackdown on further illegal fishing activities in the near future.”

In Romblon, said Magro, this pressure resulted in the increased number of policemen present during seaborne operations.

Imagine the added efficiency if commercial fishing vessels have tracking devices onboard?

Existing technologies

FAO No. 266 provides that the tracking device (called automatic location communicator or mobile tracking-transceiver unit) that will be used by fishing vessels should be BFAR-accredited.

The automatic location communicator or ALC uses radio data communications to send information about the position and activities of the vessel, and should “contain the vessel name, fishing gear, fishing ground, and other parameters contained in the vessel registration.”

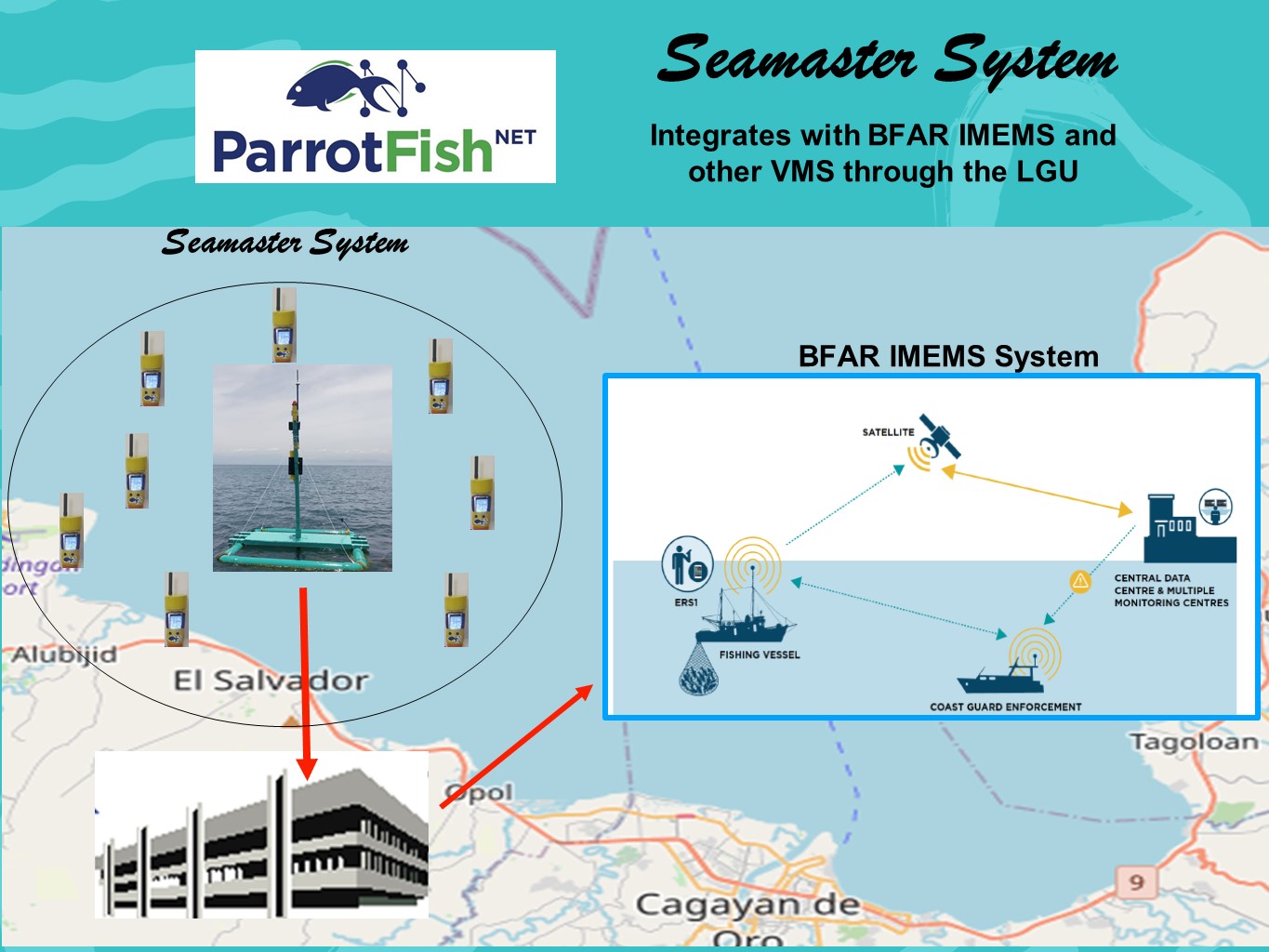

BFAR already has an accredited service provider for its Integrated Marine Environment and Monitoring System (IMEMS), a centralized satellite system that requires a receiver/transmitter (e.g., ALC), satellite subscription, and a ground station from LGUs.

BFAR has started implementing this as part of the country’s national strategy to use technology for marine environment monitoring, ensuring its sustainable and legal use.

Other technology providers and developers in the Philippines can also apply for accreditation.

Among them is the Seamaster system, composed of a portable, solar-powered GPS tracker put on the boat called “Seamate.” It comes with a buoy that can relay information (time and location) and extend the range of coverage.

Developers of the Seamaster system can apply for its accreditation and integration into the IMEMS as the existing vessel monitoring system being implemented by the government.

As a sophisticated monitoring system, the IMEMS also presents some challenges. For instance, the municipality of El Salvador in Misamis Oriental finds it expensive and highly technical for sea wardens, according to ParrotFishNet, the developer of the Seamaster system that has been working with the local government.

“IMEMS is only effective if LGUs adopt it fully,” the group said.

The Seamaster system costs P55,000, with the GPS tracker and its solar panels system costing P5,000, and its buoy costing P50,000.

Diogenes Pascua, one of the system’s developers, said a buoy can cover several registered commercial fishing vessels in a municipality, adding that it is LGU-centric because it can feed information directly to LGUs.

While LGUs can also request for information from BFAR’s vessel monitoring system, LGUs can act right away if they have 24/7 access to tracking information. This makes rescue operations a lot easier too.

Karagatan Patrol, together with several government agencies, declared the Seamaster system as the winner of the recent Karagathon contest, which sought solutions that would complement and enhance the country’s existing vessel tracking systems.

According to Karagatan Patrol’s Danny Ocampo, BFAR will look into institutionalizing the proposals (there are two other winners) within the framework of their enforcement plans, while their team will introduce the proposals to BFAR regional offices.

As for LGUs, “the budget allocation for [building the ground station and related infrastructure] will be in 2022 because the budget for next year has been set already,” said Montojo, who was among the first local leaders who called for the implementation of vessel monitoring measures.

Light detection

In recent years, mayors have turned to Karagatan Patrol and its open-access online platform that shows light detections in municipal waters all over the country using a satellite-based tool called the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite.

Karagatan Patrol provides mayors with a copy of their report to alert them about light detections within their municipal waters, and determine their sources.

These light detections don’t automatically equate to illegal activity. But since commercial fishing vessels are prohibited from the areas where the light sources occur, Karagatan Patrol alerts mayors about these detections and urges them to determine their sources.

Even during the coronavirus lockdown, which coincided with the peak fishing season in the country, there were commercial vessels that took advantage of limited police patrols, according to Karagatan Patrol.

Among the Bicol provinces, Masbate’s light detection rate remained consistently high. Based on Karagatan Patrol’s rankings, this year, Masbate had the highest number of light detections nationwide (March 22 to 28), and among provinces (May 16 to 22).

Elwin Mangampo, chair of the fisherfolk group Lambat-Bicol, said “fisherfolk from Ragay Gulf lamented the sightings of intruders despite the very strict rules during the lockdown.” Ragay Gulf spans the provinces of Masbate, Sorsogon, Albay, Camarines Sur, and Quezon.

Masbate was also among the top 5 provinces with the highest number of light detections within municipal waters in 2019.

Mangampo said the intrusions of commercial vessels in these rich fishing grounds have been a problem for municipal fisherfolk long before the lockdown.

This worsens the difficulties of law-abiding small fisherfolk as it creates unfair competition and reduces profits, including in areas with closed fishing seasons.

In a recent statement, several LGUs called on BFAR to give them access to the information generated from its vessel monitoring measures.

Under FAO No. 263 series of 2019, all coastal LGUs, as fisheries managers, are required to take on shared responsibilities for the conservation and sustainable management of shared fishery resources via their respective Fisheries Management Areas (FMAs). But at present, only 5 out of 12 FMAs have convened their management body.

Shared management

The concept of shared management has been practiced by the Gulf of Lagonoy Tuna Fishers Federation Inc since 2015, when the World Wide Fund for Nature or WWF, together with BFAR, helped small-scale fisherfolk in Lagonoy Gulf in Bicol get organized.

Since then, the group – composed of municipal fisherfolk around the Gulf – has benefited from synergized fisheries management, all while optimizing cooperation, knowledge-sharing, and enforcement.

While installing tracking devices onboard commercial vessels is not the be-all and end-all solution to the illegal fishing problem in the country, implementing and integrating them into the BFAR IMEMS via LGUs will make for accurate detections and real-time response.

Immediately knowing the type of fishery, the geographic location, and the activities will help determine the magnitude of illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing and its many social impacts, making these hopefully easier to address. – Rappler.com

This story was produced in partnership with Oceana Philippines.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.