SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

“Sigurado kang iyan ang gagamitin mo (Are you sure that’s what you’re going to use)?”

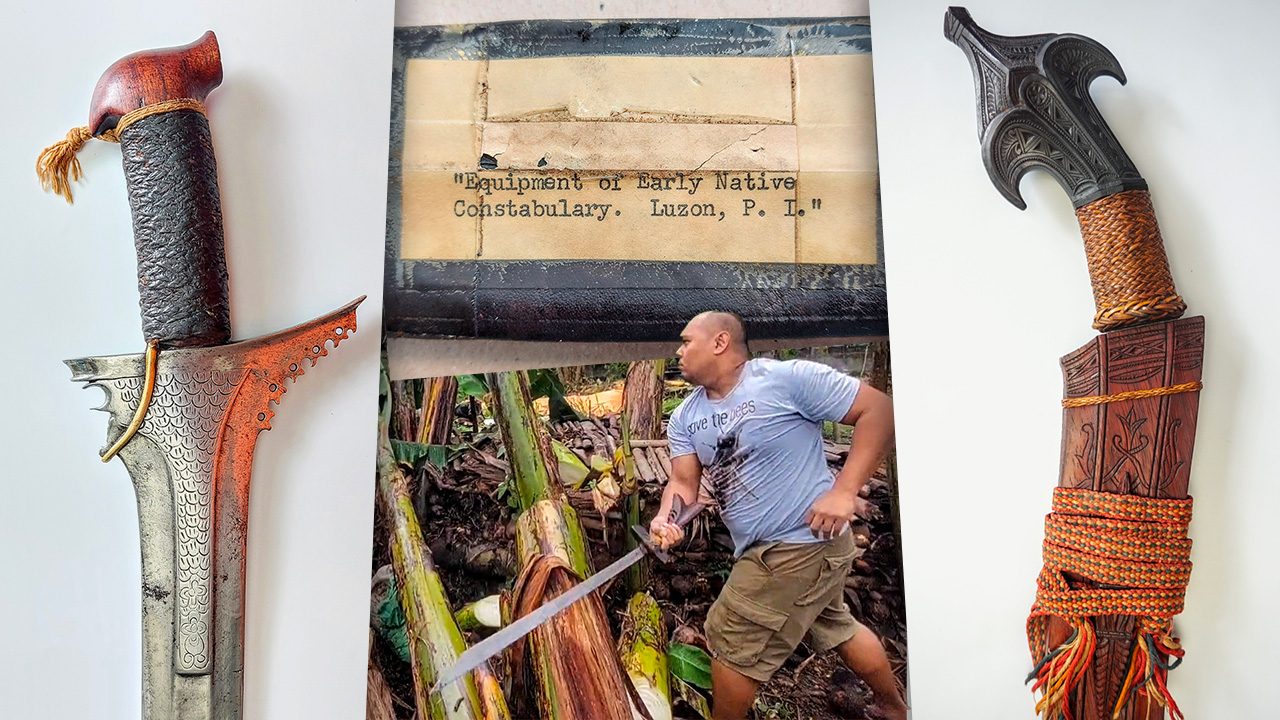

My father looked incredulously at the massive, thin-bladed war sword. The sword figures prominently in Filipino mainstream culture, thanks to the popular story and depiction of Datu Lapu-Lapu who supposedly used it to cut down Magellan (a historically inaccurate account, as noted by premier historian Dr. Ambeth Ocampo).

“Oo, gusto ko makita ang totoong bagsik nito (Yes, I want to see this weapon’s true potency),” I replied while checking the rattan-wrapped hilt grip.

There were fallen banana trees in our backyard that needed to be cleared away – perfect targets for cutting practice. The wooden handguard felt reassuring, and the pommel seemed to give me an eager, toothy grin. The antique Iranun kampilan was ready – and so was I.

(Author’s note: Training, supervision, and safety measures are required before doing test cuts, especially when using antique swords. It is also mandatory to check Batas Pambansa Blg. 6, November 21, 1978, for provisions on lawful use of bladed implements.)

Cut tests with restored antique blades is part of my personal research. I aim to validate past-era accounts of Philippine archipelago fighting blades’ performance. In colonial-era historical documentation, foreign authors always mention our fighting blades with wonder and respect. Certain tribes and organizations became known for their signature fighting blades.

The Bangsamoro tribes used a panoply of huge and heavy war blades to keep the South unconquered.

The Spanish-era cuadrilleros (indigenous police force) enforced Spanish rule using bolos provisioned with European handguards and leather sheaths.

The Waray Pulahan used their unique garab sword (also called talibon or sundang) for lopping off colonial invaders’ body parts during ambuscades or massed bolo rush.

The Bicol Cimarrones tribe used their ‘minasbad’ blades for hunting, cultural transactions, and self-defense.

Blade expert Zel Umali, who uses an inductive method to identify blades, has the following motto: “The first step is to simply look at the blade.” Different areas prefer certain edge grinds: chisel (Visayan), convex (various Luzon and Bangsamoro areas), or asymmetrical (various Luzon and Bangsamoro areas). Fighting blades would have streamlining features that improve wield character (also known by collectors and martial arts practitioners as “feel” or “balance”). These features include clip-point, false edge, wide bevel, fuller, and aggressive distal taper. The tip has its own odyssey. It may be at the middle, upper half, or lower half of the blade width. It can curve upward like a saber’s, or downward like a beak. Belly placement (or in some cases, the lack of a belly) also varies.

The cutting capabilities of our fighting blades depend on build features (steel composition, edge grind, heat treatment, hilt configuration, etc.), proper cutting technique, and target material. Generally speaking, very light, thin-spined, and narrow-width blades are best for slashing and thrusting at soft targets. Hefty, thick-spined, and wide blades have better chopping capabilities and can withstand tougher targets.

The hilt is the main provision of the wielder, because proper usage enables accurate and efficient blade strikes. Foremost blade expert Sali Nagarajen emphasized: “The hilt accounts for 50% of a traditional blade’s identity and functionality.” The hilt, whether round or polygonal in contour, fits the Filipino hand dimensions perfectly. The grip area may have a ferrule of silver, brass, iron, carabao horn, suasa (a rose-gold alloy), or rattan. The best hilts have secure weapon retention and grip options.

The pommel offers clues to the wielder’s background, ancestry, or motivation for fighting. For example, the famous Maguindanao kampilan pommel types which are popularly attributed to the crocodile (sometimes erroneously called bakunawa, a Visayan term) has alternative interpretations. According to Jesus Salon, different royal lineages crafted the pommel according to their coat-of-arms. Aside from the crocodile, there were lineages that depicted the pommel as a bird’s tail, or the dragon-like naga.

Together with the hilt, the scabbard is called the “dress” of the blade. The dress is a major indicator of the weapon’s origin and other influences. There are markings with layers of meaning, to name a few: the timeless and intricate okir/ukkil of the Bangsamoro, Visayan tribal patterns, and Luzon insignias indicating colonial or anti-colonial affiliation.

The resilient scabbard includes an attachment to the wielder’s body – textile, Manila rope, nylon, or other cord material.

Aside from combat functionality, our blades were a cultural indicator of nobility status. It’s a common misconception that highly aesthetic swords featured by museums and auction houses were the ones used by battle frontliners. In Luzon and Visayas, bolomen were provisioned with sharpened bamboo staves, makeshift or stolen guns, and farm bolos (credits to Elrik Jundis for this information). Among the Bangsamoro, warriors wielded spears, guns, and simple-dressed fighting blades.

The nobility class was composed of accomplished warriors, military officers, merchants, landowners, and those with foreign or royal lineage. A nobility blade was considered an exclusive luxury, and could not be afforded by a commoner. A passage in the Catalogo de la Exposicion General de las Filipinas published by Tipografico de Ricardo Fe (1887) stated that in the Tagalog provinces, nobility bolos were “used by wealthy indigenous people.”

Among the Bangsamoro, the double-edged sacred swords known as kris (Mindanao) and kalis (Sulu) may be for fighting or nobility depending on the dress. A kris with a wooden kakatua pommel and hemp-braided hilt grip was likely owned by a warrior. But a kris with an ivory pommel and metal-inlay hilt indicated nobility ownership. Such a kris was considered retired from battle duties, and preserved as a family heirloom or pusaka.

There is a rich trove of period photos that show members of Philippine nobility carrying gilded blades. Community leaders who preside over conflict and dispute cases wear their nobility blades to remind warring parties of their authority and wisdom (credits to Jesus Salon for this information). In the same vein, a diplomatic meeting between sovereigns – whether local or foreign – is a good venue to flaunt nobility blades. “For the apparel oft proclaims the man,” Shakespeare said – and our proud ancestors embodied this adage with their blades.

While a lot of our antique blades have been repatriated and studied by blade researchers in the past few decades, more anthropological legwork is necessary to chart blade development vis-a-vis cultural practices and historical eras. To paraphrase blade expert Braulio Agudelo: blade research is a reclamation of lost or long-hidden narratives that can strengthen national identity. With each shred of blade-related information, we recover priceless pieces of our proud and diverse cultures, and pay homage to a long history of valiant armed struggle. – Rappler.com

Author’s note: This article is dedicated to my family – to my wife, parents, and in-laws, for tolerating and even supporting my traditional blade research. My profuse thanks goes to aforementioned blade experts, mentors, friends, fellow collectors, and subject matter consultants; to Randy Salazar (head honcho of Filipino Traditional Blades research group), and Lorenz Lasco (blade expert specializing on symbolism and etymology). Lastly – this is a salute to the countless, nameless blade-wielding patriots who fought against colonial rule and oppression.

My blade cut test videos can be viewed here.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.