SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

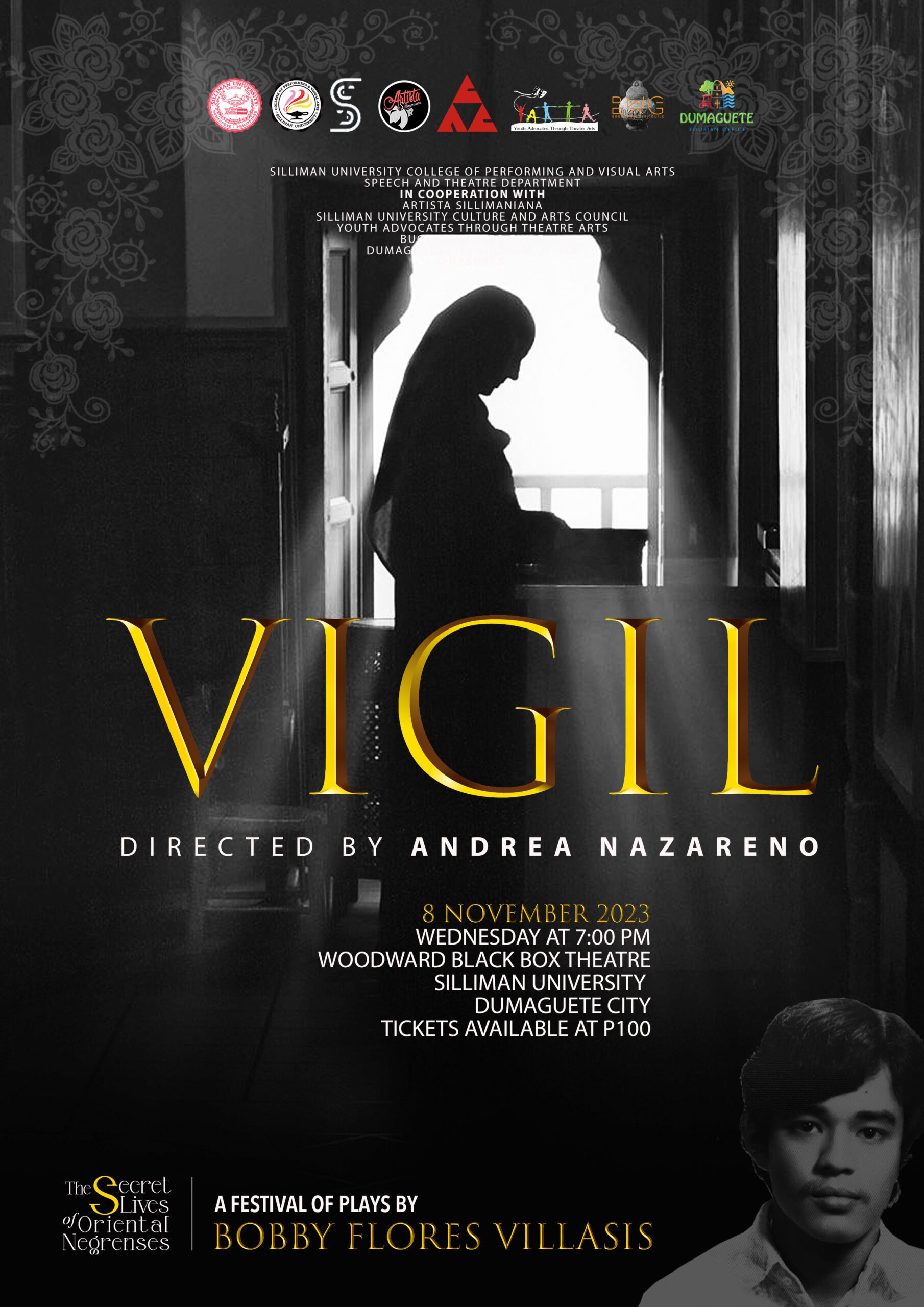

For the first time ever, four of the Palanca-winning plays by the late Dumaguete writer Bobby Flores Villasis will be performed in the place that inspired them — Negros Oriental — in a festival rightfully titled The Secret Lives of Oriental Negrenses, on select dates from November 8 to 18 at the Woodward Blackbox Theater in Silliman University, Dumaguete City. Mr. Villasis died early this year, on May 2, without seeing any of his plays staged; his birth anniversary is on November 16. One can say this is a birthday gift for Mr. Villasis that is many years in the making — and also for Oriental Negrenses, a chance to see their stories come to life.

Staging the local

For the longest time, whenever theater artists in Dumaguete, especially from Silliman University, put on a play, the invariable title chosen would always be material from Manila, by Manila authors. Whenever this happens, I’d usually go: “Manila na pud…” Given how I vent about the Manila-centric nature of our culture, the reality regularly pained me because Dumaguete is supposed to be a City of Literature, and we do have an abundance of writers and playwrights here — but their plays don’t seem to get any traction about being staged locally.

Case in point: In My Father’s House by Dumaguete playwright Elsa Martinez Coscolluela. A play about a Dumaguete family torn apart by World War II, it won the Palanca Award in 1980, but was first staged not in Dumaguete but by the University of the Philippines Playwrights’ Theatre at the Faculty Center Studio (and then later at Teatro Hermogenes Ylagan in UP Diliman, and at the Cultural Center of the Philippines’ Tanghalang Huseng Batute) in 1987. In 1989, they restaged it at the Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero Theater, but with a Filipino translation, Sa Tahanan ng Aking Ama, by Raul Regalado. That year, it became the country’s official entry in the 11th Singapore Drama Festival. According to the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art, its productions in the United States included one at the Astor Place Theater in New York by the Ma-Yi Theater Company in 1990, and then at the Hudson Theatre in Los Angeles by Stage West in 1996, both directed by Chito Jao Garces. In Japan, it was presented in 1995 at the Clapbard Garden Theatre in Kyoto by the Kapatiran-Kyoto, co-directed by Matthew M. Santamaria and Josefina Estrella. In 2010, a new translation in Filipino by Jerry Respeto was presented by ENTABLADO at the Rizal Mini Theater at the Ateneo de Manila University, co-directed by Respeto and Jethro Tenorio.

That play was being staged everywhere except the place it truly belonged to: Dumaguete. Only in 2013, 33 years after it won the Palanca, did the play see production at the Luce Auditorium, with Amiel Leonardia directing.

Many other award-winning plays by Dumaguete and Silliman playwrights — Lemuel Torrevillas, Leoncio Deriada, Edilberto Tiempo, Aida Rivera-Ford, Linda Faigao-Hall, Luna Griño-Inocian, Ephraim Bejar, Beryl Andrea Delicana, Michael Aaron Gomez, and so many others — suffer from the same oversight.

One can understand why: Manila plays have the most recall power especially among younger theater artists because they are constantly being staged and talked about, especially on social media. And they’re also accessible. Whereas, with Dumaguete plays — where can we even begin to get hold of copies of these plays? And how come nobody talks about them? It’s a conundrum.

It’s not that there is no universality in locally-set plays: the playwright Alexandra May Cardoso took my short story “The Sugilanon of Epefania’s Heartbreak,” set in Bayawan at the turn of the last century, and adapted it into the fabulously written Ang Sugilanon sa Kabiguan ni Epefania, and that play, which started its journey at the CCP’s Virgin Labfest in 2016, has been performed everywhere — and people seem to love it.

Jumpstarting with Villasis

A few months ago, soon after Mr. Villasis died, Dessa Quesada-Palm, founder of Dumaguete’s Youth Advocates Through Theatre Arts, hatched a plan: why don’t we ask senior directing majors from Silliman to stage plays by Dumaguete playwrights, and why don’t we begin with plays by Mr. Villasis? When he passed away after a long illness, the Dumaguete writer left behind a great array of literary works and books that defined a life dedicated to creative writing. He was also a persevering cultural worker, having spent most of his working life as the cultural officer of the Negros Oriental Provincial Tourism Office, but it is his poems and his short stories and his plays — which chronicle the storied lives of Oriental Negrenses from Bayawan to Dumaguete — that would come to be the foundation of his legacy.

In his 1998 book Demigod and Other Selections, Mr. Villasis first gathered together a sampling of his oeuvre, anthologizing plays, poems, and short stories that showed his unique worldview, crafted with obvious mentorship from teachers like Edith Tiempo, Edilberto Tiempo, and Albert Faurot. In his 2001 short story collection, Suite Bergamasque, he embarked on an even more ambitious literary project: gathering interlinked short stories that told, as a whole, the dazzling and devastating lives of the denizens of Dumaguete’s Rizal Boulevard, particularly the families of local sugar barons whose mansions — colloquially called the Sugar Houses — line the seafront. The book became Dumaguete’s answer to James Joyce’s Dubliners or Carlos Ojeda Aureus’ Nagueños.

Of particular interest, however, are his plays, for which he won an impressive number of Palanca Awards, seven in all, which include Vigil (first prize for one-act play, 1978), Demigod (second prize for one-act play, 1979), Fiesta (first prize for one-act play, 1987), Salcedo (first prize for one-act play, 1988), Brisbane (second prize for one-act play, 1989), Eidolon (honorable mention for full-length Play, 1990), and Caves (third prize for one-act play, 1994). They are a mix of historical and domestic dramas, but all of them invariably dramatize the secret lives and public sorrows of privileged Oriental Negrense families. These plays were acclaimed in their time, but they have never been staged, even during Villasis’ lifetime.

The festival changes this.

Vigil

Opening the festival is Vigil, directed by Andrea Nazareno, which bowed November 8. I had a raucous good time watching it, and guffawed at the unexpected queer sensibilities I had no idea it possessed. But one could readily see traces of Nick Joaquin’s Portrait of the Artist as Filipino (the unseen father in the next room, plus the bickering women, plus the strapping young man in their midst), plus the glorious madness of women in Tennessee Williams’ plays, plus the paraplegic plot of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (the one with Joan Crawford and Bette Davis) thrown in for good measure.

That’s a lot of queer ur-texts to see limning the lines in this play about a nun named Manul (played by Lady Elmido) who comes out of the convent to take care of her overbearing paraplegic mother (played by Jecho Adrian Ponce). Things go awry when the father comes home to die after leaving them eight years ago for another woman, and as if that is not enough, the other woman (played by Rhayana Marie Dalisay) enters the picture during a stormy night — and soon secrets and hijinks are revealed!

That ending, which involves an inevitable sexual romp that happens right in front of a paralyzed woman who is all but forced to get out of bed in sheer horror, was something else: it is the definition of choice, and I am glad Villasis chose to end the story this way.

Then there’s the fact that Nazareno had cast a queer man (Ponce) in the role of The Mother, which made everything all the more camp. Dalisay acquitted herself well as Ponce’s foil, but what would have completed the whole draggish illusion Nazareno (probably unwittingly) started would have been to cast another queer man as The Other Woman. Because for these two, to borrow from drag terminology, the “library” was way wide open, and they were reading each other to filth! (Ponce’s exquisite line reading of “I…hate…you” or his “You haven’t even begun to work on anything successfully!” deserves a Tony Award.)

It was all melodramatic fun, for sure. Certainly not perfect — the production design needed a more imaginative rendering, the sound design was deeply wanting, and sometimes the actors’ voices could not be heard because of challenges of projection and enunciation — but I have no deep complaints. Some might even say the play is dated — but I think literature that provides a snapshot of olden times and olden ways is its own valuable thing. True, the English deployed in the dialogue (“Husk and chaff!”) had an unreal quality to it that I somehow liked, although I also kept wondering: what if this play was translated to the Binisaya/Kiniray-a of Tolong Viejo (the old name of Bayawan), which is the setting of this overheated drama? The impact would probably be more considerable, but I can appreciate this play for the gifts it brings, foremost of which is recalling the unique voice of Bobby Villasis.

Upcoming plays

The rest of the festival showcases the following plays:

Demigod, directed by Elouise Zapanta, on November 11, Saturday at 8 pm. In this play, we are transported to Bacong, Negros Oriental in 1898. It has been 300 years since the start of the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, and discontent is everywhere. People are starving and guardia civiles are watching. A revolution has started, led by none other than Pantaleon Villegas, aka Leon Kilat, and no one can catch him. He is quick like lightning. But too much light can blind you. Be careful who you trust. In these trying times, faith will be tested and love will be questioned.

Salcedo, directed by Gillian Inocente, on November 15, Wednesday at 7 pm. The play follows the members of the Salcedo household, Lourding’s family, along with their close friends, the Bouffards, who are mourning the loss of Lourding’s husband, Pedrito. Amidst this period of grief, Lourding grapples with the challenges she encounters in her relationship with her daughters, and the Salcedo retainer leading to a surprising revelation.

And Fiesta, directed by Neve-Rienne Fuentes, on November 18, Saturday at 7 pm. The play takes place during fiesta in Bayawan, which is something everyone looks forward to, except at the Ragada household. For 20 years, Ines Ragada has been a thorn in the side of Corito, Manuel, and Soling. But everything changed with the arrival of Lucia Solon, and dark secrets and big revelations are revealed.

The productions are all under the auspices of the Speech and Theatre Department of the Silliman University College of Performing and Visual Arts, in cooperation with Artista Sillimaniana, the Silliman University Culture and Arts Council, Youth Advocates through Theatre Arts, Buglas Writers Guild, and the Dumaguete City Tourism Office. The event is also one of the highlights of the 75th Charter Anniversary of Dumaguete City going into its Diamond Jubilee Year. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.