SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Emotions are core to our human experience, but seeing “negative” emotions in our children – anger, fear, jealousy, envy, sadness, resentment – can make us uncomfortable.

Strong emotions in our kids may trigger our own emotional reactions, and we may feel lost about the best way to respond.

Many of today’s adults grew up not talking about emotions. But as modern parents, we’re told we need to teach our children about their feelings to build their resilience. So how can you encourage your children to talk about their feelings?

Research shows kids learn about emotions in four key ways: our parenting, how we explicitly teach them, our behavior and the family environment.

1) Our parenting helps kids name, express, and manage emotions

As parents, we play an important role in helping children name, express, and manage their emotions.

But this is often not easy. We might be comfortable teaching our children to recognize when they are hungry, tired, and thirsty, but be focused on stopping children’s sadness, fears, or anger, rather than on teaching about these emotions.

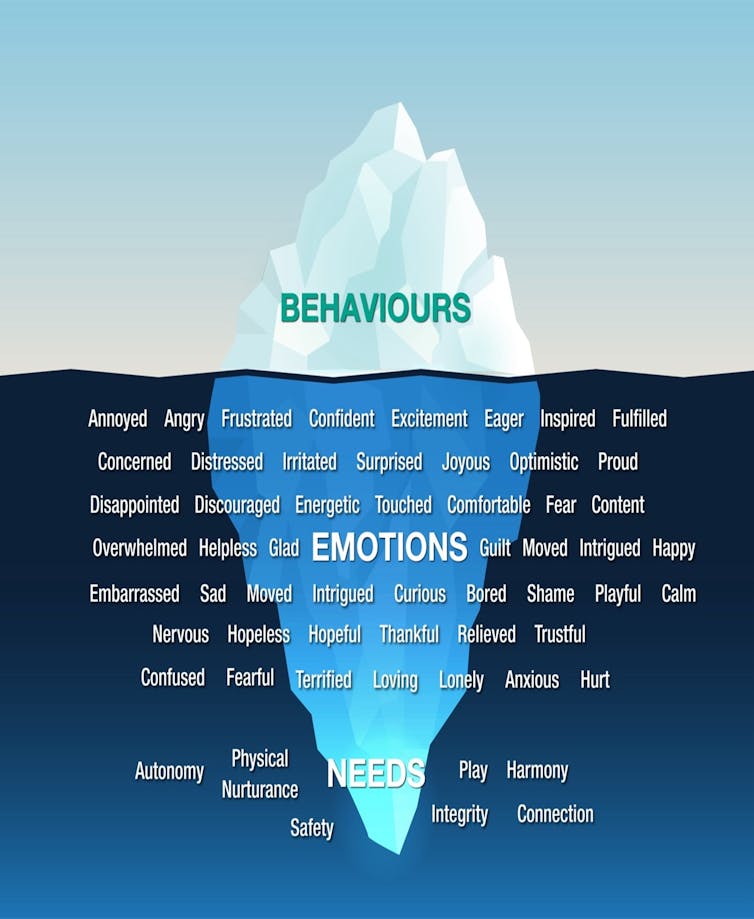

Everyone feels a range of emotions, and the “negative” emotions are not inherently bad. Emotions are signals that are important for our survival and help us to understand ourselves and our world. Children often “act out” their emotions, rather than talking about how they feel.

When we teach kids that all emotions are healthy, they learn to trust themselves, feel more comfortable sharing their feelings, and view emotions as brief experiences that pass.

So, what should we say in the moment?

- Start by describing what you see or observe. “You sound sad/angry?” or “You are looking a little quiet.”

- We often don’t know exactly what our child is feeling. Be tentative and check: “You look frustrated, is that right?”

- Validate: “That situation was really hard, no wonder you’re frustrated.”

- When our child is upset, we don’t need to say much. Try to listen and connect through eye contact and gentle touch. As University of Houston professor of social work and author Brené Brown reminds us, it is not about having the right words, but instead about offering support and connection.

- Avoid trying to fix (problem-solve) or distract your child when they are emotional. Support kids to acknowledge and “sit with” their feelings.

- Older children and teens may learn how to start masking their emotions, so we might only see their challenging behaviours. Imagine their behavior is the tip of an iceberg, caused by emotions under the surface. Try connecting with their emotion rather than focusing only on the behavior, “You slammed your door, are you feeling upset?”

2) Parents can explicitly teach kids about emotions

When everyone’s calm (not when you or your child are upset), we can teach kids about emotions.

We can start conversations about emotions based on almost anything your child is interested in, a TV show, video game, movie, or book they’re reading. A great movie for starting the conversation is Inside Out.

Watching emotions in fictional characters normalizes emotions as a universal experience and helps kids to recognize more subtle types of emotions and different ways to express and manage emotions.

For older kids who’ve become more self-conscious, try having these discussions when not directly looking at them, in the car, or during an activity (walking, kicking a ball, watching a movie together). Some kids open up more at bedtime. Try to listen more and talk less.

3) Children watch and learn from us

Many of us grew up in families where parents did not teach us about emotions, or they were poor role models for expressing emotions in healthy ways.

If this is the case, it’s common to view emotions as bad and unhelpful, and believe it’s not good to dwell on feelings.

As a result, it can be hard to watch our children experiencing strong negative emotions. If you’re feeling triggered by your child’s emotion, it will help to pause. You can leave the room if necessary. It’s healthy to role-model to kids taking a break when we feel overwhelmed.

If we make a mistake as parents and act in ways we’re not proud of, this is a great opportunity to model to our kids how to make amends.

Explain what you were feeling, that your actions were not okay, and apologize. This gives kids a template for making amends themselves, which is a critical relationship skill.

If you often struggle managing your own emotions, learning about emotions is a good start. Two great books are:

- Permission to Feel (Marc Brackett)

- The A to Z of Feelings (Andrew Fuller and Sam Fuller)

4) Kids are affected by relationships in the family

Emotions are contagious. Kids are affected by other relationships in the family, including conflict between parents.

Remember, conflict is a healthy human experience and cannot be eliminated. Instead, it’s important to show kids healthy conflict, where we all express emotions in a respectful way.

It’s also important that kids see healthy conflict resolution.

Where can you get help?

Here are three evidence-based parenting programs focused on helping parents teach children about emotions:

- Tuning in to Kids/Teens focuses on the emotional connection between parents/carers and their children, from toddlers to teens

- Partners in Parenting is designed to help you raise your teenager 12-17 years to prevent depression and anxiety

- Circle Of Security Parenting improves child development by strengthening the parent-child attachment when children are aged 0-12 years.

– The Conversation|Rappler.com

Elizabeth Westrupp is an Associate Professor in Psychology, Deakin University.

Christiane Kehoe is a Research Manager and Program Specialist for Tuning in to Kids, The University of Melbourne.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.