SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – It’s very hard to be taken seriously when you tell people you enjoy reading children’s books. After all, what are children’s stories but words and pictures on a page, designed to tell a small person how to live the way we all think they should?

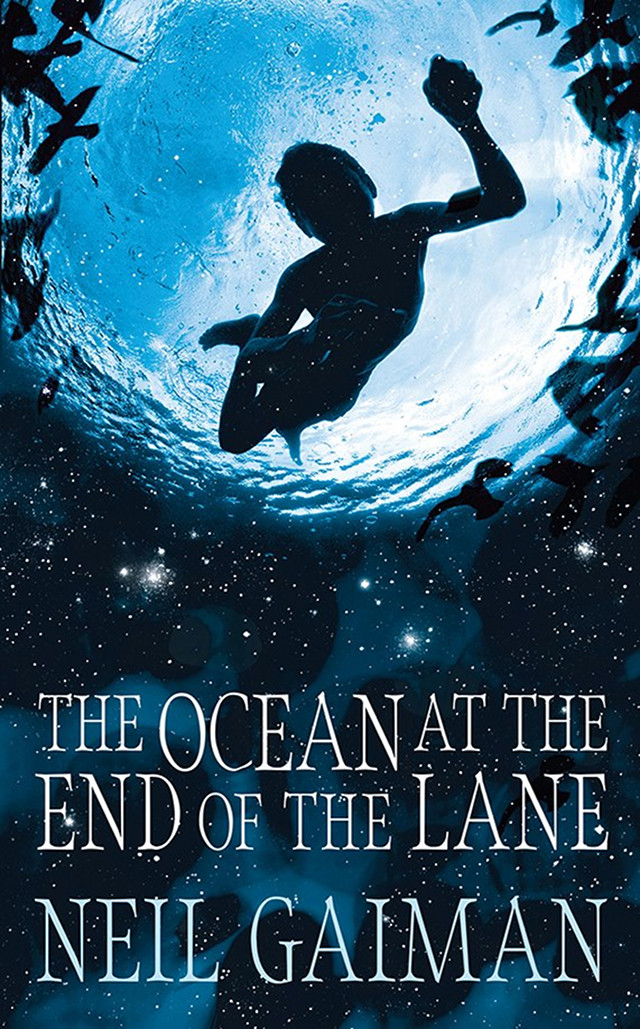

But as Maurice Sendak reminds us, via Neil Gaiman’s epigraph at the beginning of his wonderful new novel, “The Ocean at the End of the Lane,” “I remember my own childhood vividly…I knew terrible things. But I knew I mustn’t let adults know I knew. It would scare them.”

Maurice Sendak, of course, was best known for a well-loved children’s book, “Where The Wild Things Are.” But even this Caldecott award-winning picture book was not really a charming fairy tale for young children. It told the tale of Max, a naughty boy in his wolf suit, sent to bed without his supper for doing naughty things.

But a forest grew in Max’s room, and the ocean came with it. Max sailed for a day and a night, in and out of weeks, and through a year, until he came to the island where the wild things are. Sendak illustrates these creatures vividly: with large yellow eyes and sharp talon-like claws, ready to rend and tear and frighten the child.

Yet Max tames them, and he becomes a wild thing like them — fearful and uncontrolled and, yet, unspeakably lonely. So when he is given a chance to sail back home, he takes it.

When children read stories, they don’t need things explained to them. They accept, without hesitation, that wolves can come out of the walls, that a blue-jacketed rabbit can run through a vegetable garden causing trouble, that following the 3rd star to the right and heading straight on ‘til morning will take you to a magical land with fairies and pirates.

Adora Svitak reminds us in her TED Talk that “[k]ids don’t think about limitations…they just think about good ideas.” The stories we tell and remember and re-tell about our childhood are proof of that.

Reading children’s stories is not just something that we do as parents or guardians of the young, when bedtime tales are part and parcel of a child’s routine. Reading children’s stories for ourselves can remind us that there is a world outside the mundane, the normal, the ordinary.

Whether we’re reading about a young girl writing to Mr. Henshaw or a titian-haird sleuth solving mysteries with her friends, we remember a time when we were wondering about the world, ready for any adventures that await us. We were fearless.

Stories for children break the boundaries between the real and the not-so, when the world becomes aligned with the magical, the mysterious. The child’s understanding of the world is different from ours, because facts and figures haven’t been hammered into their heads yet. Everything is new, and yet not so.

When they see a butterfly flap its wings and alight delicately on a flower petal, it’s as if they are seeing that moment for the first time, as if it is the first butterfly and the first flower in the world.

“I am in love with the world,” Maurice Sendak exclaims in a radio interview on NPR. He is right: when we tell stories for children, we fall in love with the world we live in, because we are seeing it again for the very first time.

But perhaps, most importantly, reading children’s stories isn’t something to be ashamed of or to be derided simply because, like any form of literature, these stories are told for the sheer pleasure of telling a story. More than being didactic tales or moralistic tales, children’s stories should be taken on their own terms — in much the same way that the child must be taken on his or her own terms.

We shouldn’t — and we don’t need to — impose our own grown-up understanding and views on something that has to be read on its own. Roald Dahl can never be compared to Tolstoy, C.S. Lewis to James Joyce, Beatrix Potter to Jane Austen.

READ: Jane Austen’s ‘Pride and Prejudice’ turns 200

But that doesn’t make them any less important, any less valuable and the subject matter that they tackle any less serious.

To read children’s stories is to give ourselves up to the pleasure of the story, to see the play between words and sounds and pictures, to remember how it felt to be children, however fleeting the moment may be. As John Green points out, we tell stories and we listen to stories because “we’re after the terrifying, otherworldly feeling of what lies in wait.”

And what a thrilling wait that is. – Rappler.com

Gabriela Lee is a writer, a teacher and an amateur fangirl. She loves reading and writing children’s and young adult fiction, speculative fiction and any story that features a time-travelling madman in a box. Her fiction and poetry have been published in the Philippines, Singapore and the United States. She currently teaches at the University of the Philippines. You can find her online at http://about.me/gabrielalee.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.