SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

In many ways, we look back on our history through a study of a series of events, making sense of the many eras of our past according to their chronology. Philippine history has been taught as a division of many periods, starting from our pre-colonial life up to contemporary times. Yet, for all the ways we view it at its sheer scale, what if we could disentangle its many nuances by zooming in on an item we use every day, such as the dress or pants we wear? Because, more than its materiality, clothes can tell our histories, or so, at least, this is what the 39th National Book Award Best Book in History, Stephanie Coo’s Clothing the Colony: Nineteenth-Century Philippine Sartorial Culture, 1820–1896 (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2019) aims to prove.

Perhaps, due to the context of a Spanish colonial society fraught with uncertainties, we turned to our sartorial choices beyond utility to hint at our yearnings, vulnerabilities, and what we want to show or hide. The traje de mestiza or barong tagalog we were wearing in huge silhouettes while strolling along the cobbled stoned streets of Manila’s Escolta speaks volumes. In Clothing the Colony, for instance, Stephanie Coo unravels the 19th century through the wardrobe — clothing is seen at a shifting crossroads of internal and external inuences across changing socio-economic, political, and cultural landscapes. In deconstructing the story within the fabric and the fabric within the story, Coo did not leave anything untouched in the 550-page book divided into six chapters, having pored over several sources across the globe as she should as a historian educated in Manila, Beijing, and Nice.

She analyzes the many layers of a delicate colonial society by exploring the meanings of the sartorial sensibilities of the colonizers and the colonized from across the spectrum of race and class that dominated the 19th century. The clothing of children, men, and women, be they Spanish, Filipino, or Chinese, from the lower class to the mestizos and to the elites are situated against the tensions of a period that came before our national awakening in the latter part of the century. In an era especially informed by hierarchy, the appearances of agents such as men and women, and the interplay between these two genders, are analyzed to demonstrate the “dominance” and “subordination” among these groups. Coo narrates the aspirations of our ilustrados, “talented and well-educated as they were, as expressed in the Western suit.“ Their donning of the clothing of another society to acquire a voice was a classical colonial statement of equality with their colonial masters. In Western suits, they presented themselves as equally educated, competent, and tenacious men who were poised for leadership in the new order they were hoping would materialize,” she writes.

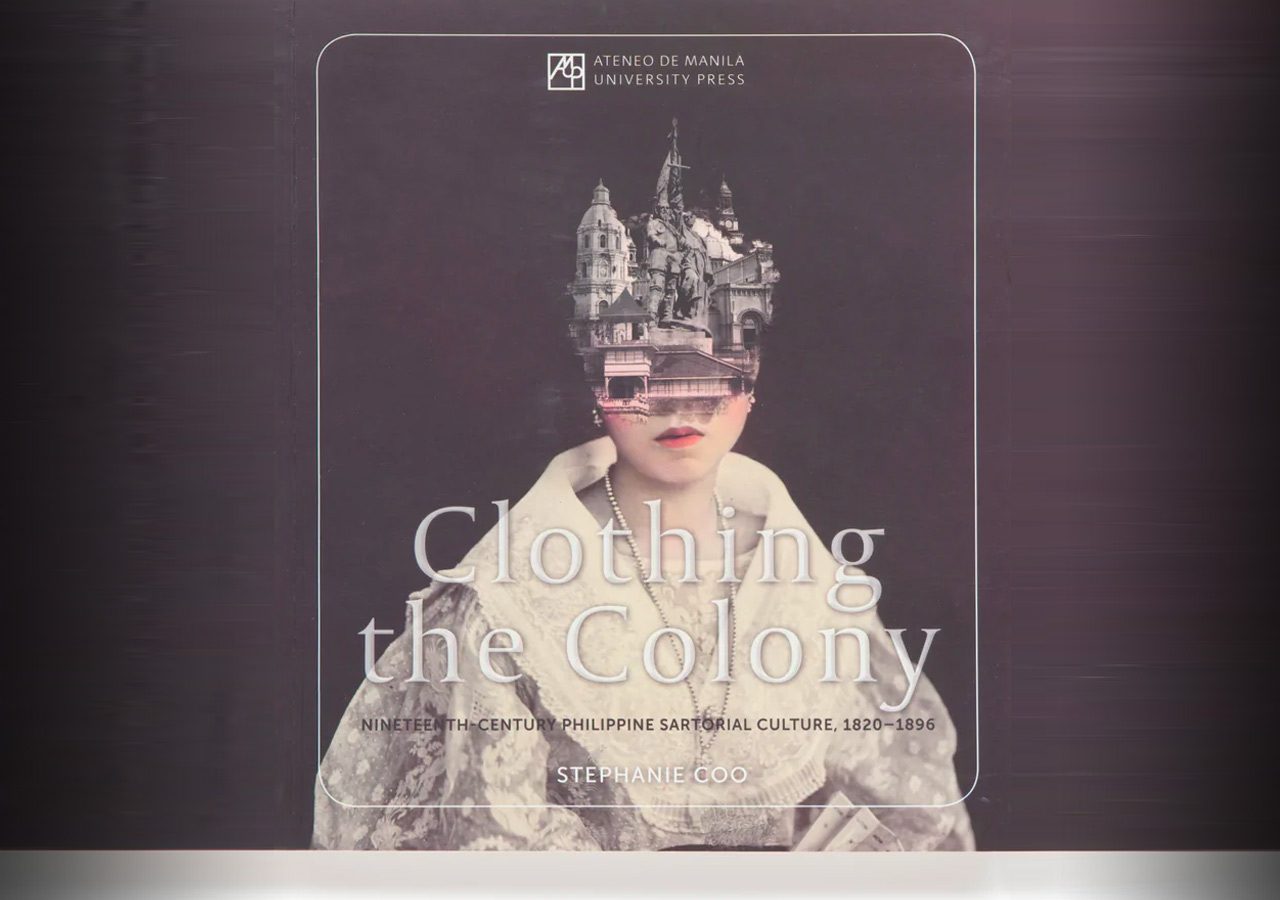

Towards the beginning of the Filipino revolution in 1896, clothing, while characterized by “divergence” in the early part of the century as Coo explains, also revealed the point in time where “convergence” or how we have found our national becoming came about. As the country opened itself further to the exchange of goods and ideas from beyond our shores and as these inuences permeated the colony, local and regional variances in the appearances of Filipinos across sectors were said to have disappeared over time. Coo paints in Clothing the Colony a comprehensive history of our struggle and unication through the fabric, and her use of several photos from various libraries and museums around the world serves to enrich and balance her encyclopedic study that can get exhaustive at times for the common reader, but necessary nevertheless in its extensive inquiry for the academics and creatives. Clothing, far from its seeming trivialities, is analyzed as it never has been before. The experience of reading the book wouldn’t be complete without the gorgeous design by Felix Mago Miguel Jr., including a cover that showcases a portrait of a woman dressed in a striking local gown blending with a collage of iconic Philippine sculpture and architecture, and the elegant choice of paper in silky cream.

Given its scope, the book is indeed many things at once. It’s about the history of the Philippines and its colonial times, but it’s also about the place of clothing in relation to its wider setting. Coo recognizes the complexity of the subject matter by situating the garment as if inside an infinite room of mirrors, seeing the many implications of every cut, shape, and pattern across boundaries, treading the stormy waters of stereotypes to look beyond the lure of easy categorization. Yet, as all-encompassing as it is, at the heart of the book lies an enduring interest in the materiality of local clothing per se amid sartorial traditions, in the way we used to take pains to dress in exquisite local fabrics such as piña, handwoven from the bers of pineapple plant and has been used to create the barong tagalog, and jusi, from the bers of abaca, as a grand testament of who we are. The book began, if it’s any indication, with Coo recounting her childhood, surrounded by several “wooden baul” of local textiles of all kinds that her grandmother collected through the years.

It is no wonder why the author is just as passionate as she is in the historical narratives layered within our textiles as she is in its material. More than our clothing’s cultural signicance, the composition of our traditional fabrics is in itself worthy of admiration. Piña, as the queen of Philippine textiles, is a beautiful contradiction in literal form. Translucent, soft, yet rigid, it’s an ethereal fabric, made up of the many bers of the pineapple plant, that veils over the skin like clouds of smoke to “provoke the imagination.” Such a type of fabric also eludes mechanization and can only be turned into a wearable piece through the adept hands of weavers in long, laborious processes. The colonial society that Coo writes about, amid its parade of pomp and vanities, was rendered through the seductive beauty of local textiles.

Our present may do well to turn to our sartorial traditions for inspiration if the past is told through the nest of our fabrics. Informed by the unrelenting speed of consumption and production, much of modern life is spent in a sea of clinical buildings devoid of the artful intricacies of history, or of maybe, perhaps, our humanity. Most of the clothes we wear have been produced, for instance, in anonymous factories in developing countries violating labor conditions and dependent on the [un]sustainable cycle of trends. But the fast yet fashionable, of course, sells, and at an accessible price. Just as modernity in our lifestyles necessitates these wastes, these wastes also help us catch up with the neverending rush of modernity.

Yet, until when do we allow to reect our current stories on synthetic fabrics, and until when do we engage in a culture that thrives on discarding? The answer isn’t simple. But maybe, there is a way for nostalgia to compromise and be imbued in the weaving of our present, as Coo, perhaps, yearns for in writing her award-winning book. – Rappler.com

Addie Pobre is the project manager of the 39th National Book Awards.

After two years of going virtual, the Manila International Book Fair (MIBF) is finally returning live this year at the SMX Convention Center, Mall of Asia Complex in Pasay City from September 15 to 18.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.