SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The time to make up your mind about a book is never. To many: a weak position from which to talk about a written work. And if the author themself happen to strike readers as one of those types unable to answer “what now?” by the last few pages, I imagine both parties coming out of the ordeal feeling two vastly different strains of uncertainty: The reader seeks answers, the writer eternally grapples with the freedom of irregularity.

These statements are reductive for many reasons, but this is a scenario that I have come to observe as being possibly endemic to the essay as a form, a term often used interchangeably with creative nonfiction (for its part a term that is in fact as vague as it sounds).

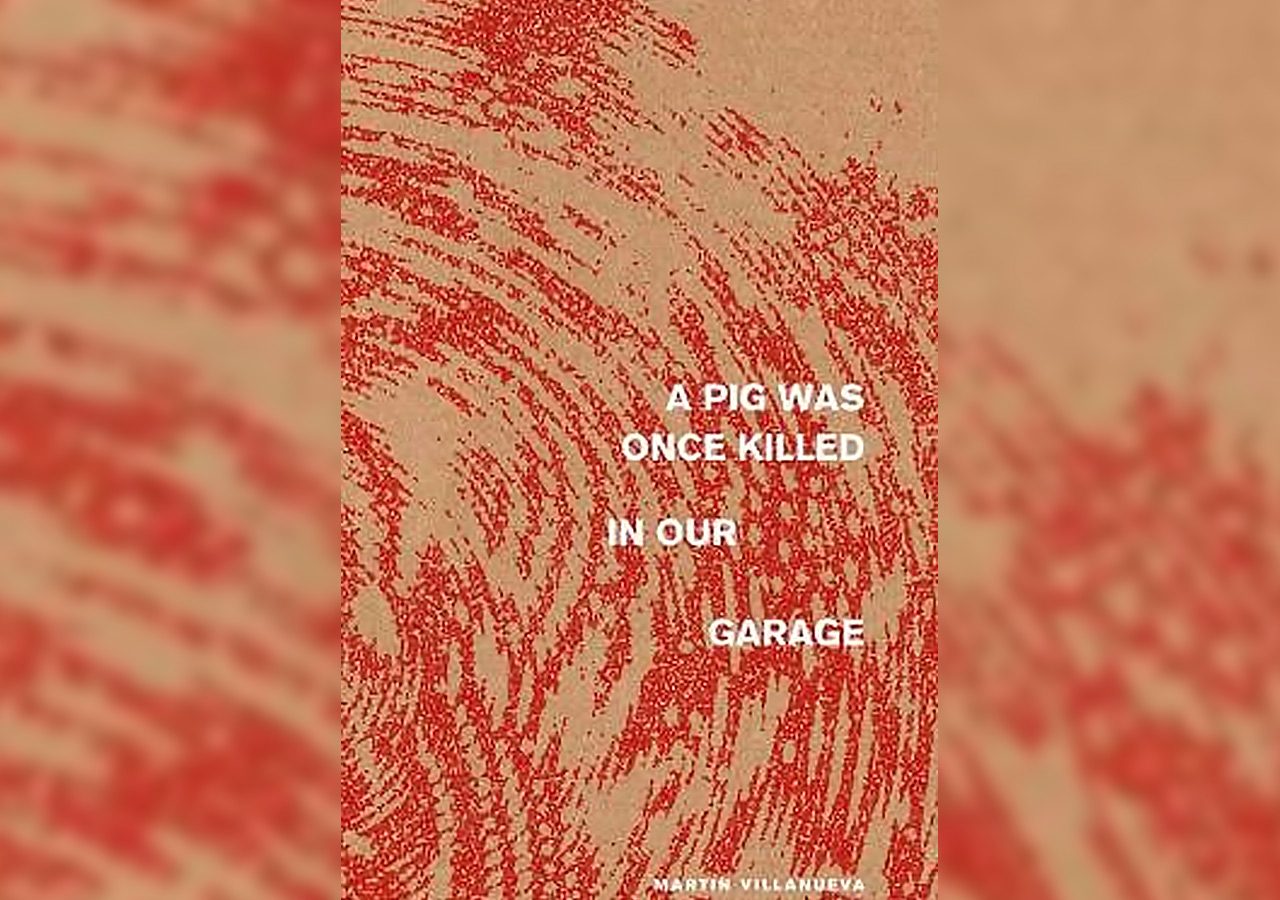

What to make of the genre’s supposed limitlessness and formlessness, its lack of a defining marker? The anecdotes in Martin Villanueva’s A Pig Was Once Killed In Our Garage, the stuff you are supposed to recount when asked what the book is about, are presented in neat, little fragments so carefully curated and organized, you get a collection of memories and ideas more reminiscent of a catalogue than a typical essay collection.

The stories here are varied and personal, from Villanueva’s childhood in Indonesia, to his treatment from bone cancer, his beginnings as a writer and teacher, and his relationship with his parents, which are sometimes interspersed with meditations on art and subjectivity.

Avid readers of essays may have come to expect the common technique of interweaving anecdotes with reflections, so much so that its desired effect fails to veil it as a convenient contrivance. But Villanueva is endlessly conscious about form. Perhaps as a consequence of its fragmentary, catalogue-like format, many of the delineations between narrative and idea are clear and definite. The bulk of the book’s non-anecdotal portions are cleanly sectioned off as mini treatises on writing nonfiction which somehow read as simultaneously intellectual and personal. Students of creative writing will find these sections to be valuable reading.

Clearly influenced by Joan Didion (whose The White Album comes up at least twice in the book, if I remember correctly), Villanueva is all too aware of that dictum about telling stories in order to live – the imposition of a narrative on what are otherwise disparate and arbitrary fragments that we accumulate throughout our lives. I suppose this is partly where the concern for and immense interest in form comes from, an extension of that idea of Didion’s largely having to do with the question of control. To choose to write about your life is to impose control over it – force it into a mold of your own devising, and from there the heart of the act shifts to the how (and occasionally, the why).

This is what Villanueva consistently problematizes throughout the book. And it’s a particularly tricky thing to do with creative nonfiction as your medium – a format in which concern over veracity kills any potential for experimentation, a format in which to universalize and to have your readers empathize with you is to save yourself from the discomfort of thought, a medium in which merely recalling your life story merits attention by virtue of its having happened.

How do you write towards meaning? If it’s lazy to universalize and coherence is an illusion that writers impose upon disparate images, then is it better to catalogue, to simply document without forcing an overarching narrative?

“The events of our lives are all but anecdotes. Still, to maintain that to respond is to simply illustrate towards remembering seems but an empty gesture by the privileged subject position from which I write. I don’t know where I’m going with this and I think that’s precisely the problem,” Villanueva writes.

By foregrounding poetics and discourse about language and subjectivity, the poet and essayist has written a book that deftly illustrates the varied issues it seeks to address (or at the very least speak about), and offers no answers in the process. Which is exciting to find in a (nonfiction) book these days. However contrived it may sound, sometimes the actual experience of reading the problematizing of a deceptively simple matter is more compelling, more illuminating, than being offered certainty at the end of a book. Villanueva is a thoughtful, skeptical narrator, careful about what he puts on the page, which are composed yet vulnerable sketches of a self rendered in unsentimental language that is never devoid of depth and feeling. I have to say, though, that should the book strike readers as sometimes too self-serious, I will only half disagree with them. – Rappler.com

A Pig Was Once Killed In Our Garage was a finalist for Best Book of Essays at the 39th National Book Awards.

After two years of going virtual, the Manila International Book Fair (MIBF) is finally returning live this year at the SMX Convention Center, Mall of Asia Complex in Pasay City from September 15 to 18.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.