SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

CALIFORNIA, USA – Mexican American civil rights leader César Chávez is the poster child of the United States’ farm labor movement. A crucial cast of characters, however, lies in history’s shadows: the Filipino farmworkers – the Delano Manongs – who ignited the first spark. (READ: Alex Esclamado: The invisible giant)

Manong is a term of respect that roughly translates to “older brother” in Ilocano, a Filipino language. The Manong Generation refers to a wave of Filipino men who immigrated to the US in the 1920s and 1930s.

Today, controversy still brews over what some call the Manongs’ “erasure” from the movement. Last month, a crowd of Filipino Americans took to the streets outside Mann’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood to protest the premiere of actor-director Diego Luna’s biopic, Chávez. (READ: New Cesar Chavez film omits Filipino farm leaders from story)

Coincidentally, Fil-Am director Marissa Aroy’s documentary, Delano Manongs, had premiered in Oakland, California, just a few weeks earlier.

“[Chávez’s] narrative perpetuates the myth that César Chávez was a one-man movement,” said one protester, artist-muralist Eliseo Silva.

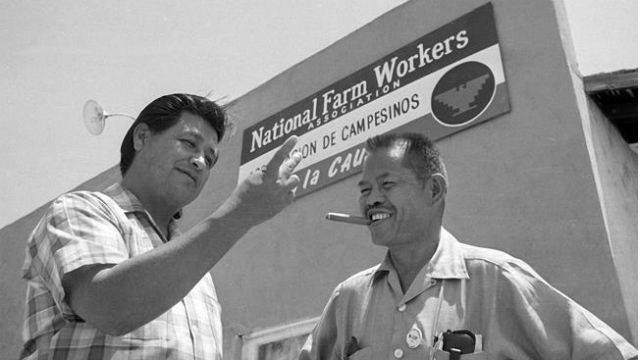

In 1965, the mostly Filipino Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) went on strike against table grape growers in Delano, California, demanding better wages and working conditions. The strike led them to merge with Chávez’s predominantly Latino National Farm Workers Association (NWFA) to form the nation’s first agricultural union, the United Farm Workers (UFW).

By the 1960s, grape pickers earned an average of 90 cents an hour, paying $2 or more each day to live in mosquito-infested shacks without electricity or plumbing. As Filipinos, the Manongs were also denied labor rights, and couldn’t own property or marry.

The grapes had just begun to ripen on September 8, 1965, when hundreds of AWOC members led by Larry Itliong flooded into Delano’s Filipino Community Center and voted to strike. “It [the strike] was like an incendiary bomb, exploding out the strike message to the workers in the vineyards,” said AWOC co-founder Philip Vera Cruz, who later served as the UFW’s second vice president.

The Manongs’ activist roots run deep. In 1924, Filipino workers led a bloody strike against sugarcane growers in Hawaii. Itliong himself joined striking lettuce workers in Washington after immigrating to the US in 1929, and formed a cannery and agricultural workers’ union in Alaska.

A foil to the intellectual, charismatic Chávez, 5-foot-tall Itliong was a straight-talking, cigar-chomping guy who had lost 3 fingers in a cannery accident – hence his nickname, “Seven Fingers.”

“I’m a mean son of a bitch in terms of my direction fighting for the rights of Filipinos,” he said in a lecture at University of California-Santa Cruz in 1976. “Because in that Constitution, it said that everybody has equal rights and justice. You’ve got to make that come about. They are not going to give it to you.” (READ: 5 US policies that Filipino Americans support)

Although growers had historically pitted Filipino and Mexican workers against each other to break strikes, the AWOC knew they needed help. So Itliong asked Chávez, then busy building the NFWA, to join the strike. Although Chávez didn’t think his group was ready, his members unanimously voted to join the Filipinos.

In August 1966, the AWOC and NFWA joined forces to form the UFW, with Chávez as president and Itliong as vice president. Since NFWA had more members, the balance of power within the UFW shifted to Chávez and other Mexican labor leaders. Once, Chávez had to defuse an attempt to limit the fledgling union to Mexicans only.

Meanwhile, UFW volunteers traveled to major US cities, where they recruited churches and other community organizations, which helped them convince millions of American families not to buy table grapes.

The Delano grape growers finally agreed to sign contracts with the UFW in 1970. Photos show Itliong seated next to Chávez as he signed them. But Itliong’s son, Johnny, said that Luna’s film “eliminated my father from the table and instead showed Itliong passively smiling in the sidelines.”

Although streets, schools, and even a national holiday bear Chávez’s name, the Delano Manongs’ only official recognitions are Los Angeles County’s Larry Itliong Day on October 25 and the potential renaming of Alvarado Middle School in Union City, California to Itliong-Vera Cruz Middle School in 2015.

And as President Obama visited Manila, after announcing a defense pact with the Philippines, the country supplies roughly 10 million overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) to 170 countries around the world. (READ: PH, US sign military deal)

Similar to the Manongs before them, overseas Filipino workers often work as nannies or housekeepers to provide for their families back home, many falling prey to trafficking and abuse. Meanwhile, NGOs like UNESCO and UNIFEM are working to improve OFW conditions globally. Let’s make sure these modern-day Manongs don’t recede into the shadows, too. – Rappler.com

This article was republished with permission from OZY.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.