SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

CAPIZ, Philippines – They were hungry. They were young and often unsupervised. They ate soil.

The Del Rosario children were playing in front of their makeshift home, twice rebuilt by neighbors. A year ago, the children played with fire and brought the house down. Last November, Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) destroyed it too.

They were not running about, but only quietly played with whatever they could find.

CAPIZ, Philippines – They were hungry. They were young and often unsupervised. They ate soil.

The Del Rosario children were playing in front of their makeshift home, twice rebuilt by neighbors. A year ago, the children played with fire and brought the house down. Last November, Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) destroyed it too.

They were not running about, but only quietly played with whatever they could find.

Luckily, they were too short to reach the bolo thrust against a tree; perhaps they were also too weak to pull it out. Their father must have left it there.

The children are aged 3, 6, and 9, but their bodies do not reflect their age. They are “stunted” – too short for their age – resulting from long-term insufficient nutrient intake.

They are also “wasted” – too thin for their height – resulting from substantial weight loss linked to starvation or disease.

Their mother, Mercy, is often away washing other people’s dirty laundry.

Luckily, they were too short to reach the bolo thrust against a tree; perhaps they were also too weak to pull it out. Their father must have left it there.

The children are aged 3, 6, and 9, but their bodies do not reflect their age. They are “stunted” – too short for their age – resulting from long-term insufficient nutrient intake.

They are also “wasted” – too thin for their height – resulting from substantial weight loss linked to starvation or disease.

Their mother, Mercy, is often away washing other people’s dirty laundry.

It was almost noon; they retreated home and waited for food. The slightly older Del Rosario child, aged 12, washed dishes in a large basin outside.

It was almost noon; they retreated home and waited for food. The slightly older Del Rosario child, aged 12, washed dishes in a large basin outside.

Their father, Josie, burnt wood – in their improvised kitchen – to cook rice. The house fogged with smoke, while the children sat on linoleum and stared into space.

When home alone, however, the world was their kitchen. They did not wait for meals; soil was everywhere.

Silent emergency

Malnutrition is a “silent emergency,” said Dr Martin Parreño of Action Against Hunger International (ACF), a humanitarian organization committed to ending child hunger.

It exists prior to disasters, the latter only worsens it. Hence the need to prioritize food security at all times.

Many do not realize that severely malnourished children are dying until it’s too late – when they are nothing but skin and bones.

Globally, 52 million children under five (equivalent to 8% of the age group) are acutely malnourished or wasted. 19 million are severely malnourished – the worst type of hunger, according to ACF. A million or more children die annually due to lack of access to treatment.

Malnourished children are less physically and mentally active. They are more vulnerable to infections, compromising bodily functions (i.e., liver, intestine, kidney, heart).

In the Philippines, more than half a million schoolchildren are severely wasted, according to the 2012-2013 data of the Department of Education (DepEd).

If untreated, malnutrition can lead to death.

Their father, Josie, burnt wood – in their improvised kitchen – to cook rice. The house fogged with smoke, while the children sat on linoleum and stared into space.

When home alone, however, the world was their kitchen. They did not wait for meals; soil was everywhere.

Silent emergency

Malnutrition is a “silent emergency,” said Dr Martin Parreño of Action Against Hunger International (ACF), a humanitarian organization committed to ending child hunger.

It exists prior to disasters, the latter only worsens it. Hence the need to prioritize food security at all times.

Many do not realize that severely malnourished children are dying until it’s too late – when they are nothing but skin and bones.

Globally, 52 million children under five (equivalent to 8% of the age group) are acutely malnourished or wasted. 19 million are severely malnourished – the worst type of hunger, according to ACF. A million or more children die annually due to lack of access to treatment.

Malnourished children are less physically and mentally active. They are more vulnerable to infections, compromising bodily functions (i.e., liver, intestine, kidney, heart).

In the Philippines, more than half a million schoolchildren are severely wasted, according to the 2012-2013 data of the Department of Education (DepEd).

If untreated, malnutrition can lead to death.

|

Clinical forms of acute malnutrition |

|

|

Marasmus |

Kwashiorkor |

|

Extremely thin, chronic deprivation of energy |

Appearing bloated due to water retention (bilateral edema) in body tissues due to poor nutrition (i.e., bloated abdomen due to enlarged liver) |

|

Associated with dehydration, frequent infections but minimal signs |

Bloating first affects the feet and legs, then moves up to the hands, arms, and face (“moon face”) |

|

“Old man face,” prominent ribs and shoulder bones, loose skin, flat butt |

No appetite, irritable, indifferent, tired, poor hair (yellowish, sparse, brittle), skin problems (dermatosis), diarrhea |

The combination of both forms is called Marasmic-Kwashiorkor .

Web of problems

Poverty and health are closely linked, analysts and families observe.

The Philippines is the world’s 10th country with the most wasted children, the 9th with the most stunted children, and the 5th with the most low birthweight infants, a 2013 Unicef report revealed.

What does this say about us?

Health advocates not only see hunger as a health problem but also a “development issue.” (READ: PH vs Hunger)

Parreño suggested how poverty both creates and results from a web of problems:

The combination of both forms is called Marasmic-Kwashiorkor .

Web of problems

Poverty and health are closely linked, analysts and families observe.

The Philippines is the world’s 10th country with the most wasted children, the 9th with the most stunted children, and the 5th with the most low birthweight infants, a 2013 Unicef report revealed.

What does this say about us?

Health advocates not only see hunger as a health problem but also a “development issue.” (READ: PH vs Hunger)

Parreño suggested how poverty both creates and results from a web of problems:

- Poverty creates ill health: people forced to live in environments making them sick (i.e., overcrowded; no sanitation, water, electricity; far from livelihood, markets)

- It creates hunger: people have no money, livelihood to buy nutritious food

- It denies access to health services: no money for transportation, medicine, infrastructure, roads)

- It creates illiteracy: lack of awareness re: agriculture, health risks, interventions

- It harms the economy: lack of money means poorer health, which means less productivity

- It is a cycle: poverty may result in poorer health, which can then worsen poverty

Mercy wakes up at 4 am to buy breakfast: pandesal.

She gives her husband P20-P50 before she leaves for work. “Pambili tanghalian,” (lunch money) she said. Josie buys biscuits (4 small packs per child) and milk (one sachet shared by 4).

Mercy earns P150-P250/day from doing laundry. With the money, she buys dinner for her family of six: 1 bag of rice (P93) and a piece of fish (P65). “Kulang pero pinagkakasya.” (Not enough, but I budget.)

“Minsan walang ulam, lugaw lang na may asukal.” (Sometimes there’s no viand, just porridge with sugar.)

Josie, a sacada (sugarcane farmer), earns P100/day. But on most days, he earns nothing. Work is seasonal.

Mercy wakes up at 4 am to buy breakfast: pandesal.

She gives her husband P20-P50 before she leaves for work. “Pambili tanghalian,” (lunch money) she said. Josie buys biscuits (4 small packs per child) and milk (one sachet shared by 4).

Mercy earns P150-P250/day from doing laundry. With the money, she buys dinner for her family of six: 1 bag of rice (P93) and a piece of fish (P65). “Kulang pero pinagkakasya.” (Not enough, but I budget.)

“Minsan walang ulam, lugaw lang na may asukal.” (Sometimes there’s no viand, just porridge with sugar.)

Josie, a sacada (sugarcane farmer), earns P100/day. But on most days, he earns nothing. Work is seasonal.

“After Yolanda (Haiyan), agriculture was devastated,” he said in Bisaya. Most people in Pontevedra, Capiz rely on agriculture for income and food.

The older Del Rosario children, aged 21 and 22, left for Manila. One sends money from working as a delivery boy, while the other has cut communication for good.

On most days, the young children are home alone; unwashed and unfed. “’Di sila nakapag-aral kasi laging may sakit,” Mercy said. (They weren’t able to study because they’re always sick.) (READ: PH education lagging behind?)

The Child and Youth Welfare Code of the Philippines speaks against leaving children unattended. However, the Philippines is yet to have stronger implementation and penalties similar to other countries.

“After Yolanda (Haiyan), agriculture was devastated,” he said in Bisaya. Most people in Pontevedra, Capiz rely on agriculture for income and food.

The older Del Rosario children, aged 21 and 22, left for Manila. One sends money from working as a delivery boy, while the other has cut communication for good.

On most days, the young children are home alone; unwashed and unfed. “’Di sila nakapag-aral kasi laging may sakit,” Mercy said. (They weren’t able to study because they’re always sick.) (READ: PH education lagging behind?)

The Child and Youth Welfare Code of the Philippines speaks against leaving children unattended. However, the Philippines is yet to have stronger implementation and penalties similar to other countries.

One November morning, two of Mercy’s children fell ill.

Blood and worms everywhere.

The 6-year-old girl vomited and defecated 250 worms, the doctor said. They lost count of the worms from the 9-year-old boy.

Educate families

After hospitalization, the children were enrolled in ACF’s Out-Patient-Therapeutic (OPT) program where they were treated with Ready-To-Use-Therapeutic-Food (RUTF) and were closely monitored by ACF, the Rural Health Unit, and barangay health workers.

One November morning, two of Mercy’s children fell ill.

Blood and worms everywhere.

The 6-year-old girl vomited and defecated 250 worms, the doctor said. They lost count of the worms from the 9-year-old boy.

Educate families

After hospitalization, the children were enrolled in ACF’s Out-Patient-Therapeutic (OPT) program where they were treated with Ready-To-Use-Therapeutic-Food (RUTF) and were closely monitored by ACF, the Rural Health Unit, and barangay health workers.

Their mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) was measured. “If it’s very small, the child’s close to dying,” Parreño said. Their MUAC was below 11.5cm, indicating severe acute malnutrition.

The parents were taught how to feed them RUTF. Treatments are based on individual assessment of each child.

Their mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) was measured. “If it’s very small, the child’s close to dying,” Parreño said. Their MUAC was below 11.5cm, indicating severe acute malnutrition.

The parents were taught how to feed them RUTF. Treatments are based on individual assessment of each child.

|

6-year old girl |

Before treatment |

After treatment |

|

MUAC |

8.6 cm |

12.2 cm |

|

Weight |

7.1 kg |

9.3 kg |

|

Height |

82.5 cm |

84.2 cm |

“’Di ko alam noon na kailangan maghugas-kamay, magpakulo ng tubig, magsabon,” Mercy admitted. (I didn’t know we had to wash hands, boil water, use soap.)

“‘Di ko sila masyadong pinasuso dati.” (I didn’t breastfeed them much before.) (READ: Status of PH moms)

The tents also provide psychosocial support. “We met parents who wanted to give up, we counselled them,” Pionclo said.

“’Di ko alam noon na kailangan maghugas-kamay, magpakulo ng tubig, magsabon,” Mercy admitted. (I didn’t know we had to wash hands, boil water, use soap.)

“‘Di ko sila masyadong pinasuso dati.” (I didn’t breastfeed them much before.) (READ: Status of PH moms)

The tents also provide psychosocial support. “We met parents who wanted to give up, we counselled them,” Pionclo said.

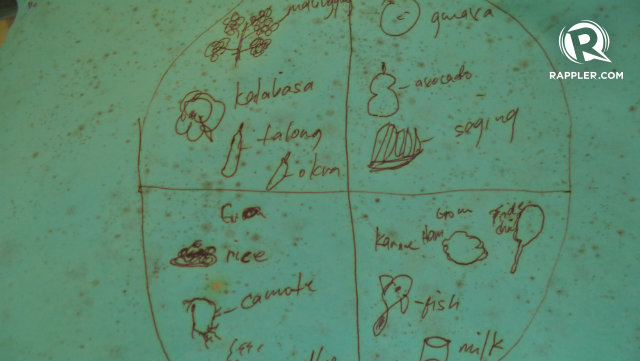

Beneficiaries are also given food vouchers which are accepted only in select stores – preventing families from purchasing junk food and vices.

The vouchers, however, are not given forever. This only helps families transition from RUTF to normal food, once children are released from the program. “We don’t want to promote dependency,” Pionclo said.

The program includes livelihood assistance and capacity-building so that parents can sustain the good health of their children.

Other parents, however, are unlike Mercy. “Ayaw nila pumuntang training. Mas gusto nila mabigyan ng pera,” Mercy shared. (They don’t like going to trainings. They prefer cash grants.)

Still fighting

Beneficiaries are also given food vouchers which are accepted only in select stores – preventing families from purchasing junk food and vices.

The vouchers, however, are not given forever. This only helps families transition from RUTF to normal food, once children are released from the program. “We don’t want to promote dependency,” Pionclo said.

The program includes livelihood assistance and capacity-building so that parents can sustain the good health of their children.

Other parents, however, are unlike Mercy. “Ayaw nila pumuntang training. Mas gusto nila mabigyan ng pera,” Mercy shared. (They don’t like going to trainings. They prefer cash grants.)

Still fighting

Though Mercy and her family are now better equipped with information, their everyday lives remain a struggle.

“Luha tumutulo sa labada. ‘Di ako nahihiya, hinihingi ko tira-tirang pagkain ng amo ko,” Mercy narratated. (Tears falling on laundry. I’m not ashamed, I asked for my employer’s leftovers.)

The couple makes sure that they bathe their children daily, but since money is tight, they often use laundry detergent instead of soap. Although budget is limited, Mercy makes sure that the children eat fruits and vegetables.

“Pinapauna ko sila kumain.” (I let them eat first.)

Once the children are in better shape, she wishes to send them to school. They will think about the tuition fee later, she said.

They used to plant vegetables in their yard, but stopped due to too much heat or too much rain. Although aware of sanitation, Mercy still cannot afford a toilet. Their backyard remains an alternative.

“Grade 6 natapos ko, asawa ko Grade 1. Hindi kami magkakaroon ng magandang trabaho. ‘Di naman bulag gobyerno. Nakikita nila kaming walang-wala. Kailangan namin ng suporta,” Mercy said.

She also encourages her friends to learn about health and nutrition, but they remain stubborn. She lectures them too about basic family planning. “Mahirap madaming anak kung di mo kayang buhayin,” she whispered. (It’s difficult to have many children if you can’t support them.)

It was getting dark. Mercy hurriedly washed the pile of dirty laundry. She wanted to go home to feed her children. – Rappler.com

To know more about ACF, you may visit their website or Facebook. You can donate here.

How can we help alleviate hunger? Share your ideas with us. You can send articles, campaigns, commentaries, infographics, research and video materials to move.ph@rappler.com. Be part of the #HungerProject.

Though Mercy and her family are now better equipped with information, their everyday lives remain a struggle.

“Luha tumutulo sa labada. ‘Di ako nahihiya, hinihingi ko tira-tirang pagkain ng amo ko,” Mercy narratated. (Tears falling on laundry. I’m not ashamed, I asked for my employer’s leftovers.)

The couple makes sure that they bathe their children daily, but since money is tight, they often use laundry detergent instead of soap. Although budget is limited, Mercy makes sure that the children eat fruits and vegetables.

“Pinapauna ko sila kumain.” (I let them eat first.)

Once the children are in better shape, she wishes to send them to school. They will think about the tuition fee later, she said.

They used to plant vegetables in their yard, but stopped due to too much heat or too much rain. Although aware of sanitation, Mercy still cannot afford a toilet. Their backyard remains an alternative.

“Grade 6 natapos ko, asawa ko Grade 1. Hindi kami magkakaroon ng magandang trabaho. ‘Di naman bulag gobyerno. Nakikita nila kaming walang-wala. Kailangan namin ng suporta,” Mercy said.

She also encourages her friends to learn about health and nutrition, but they remain stubborn. She lectures them too about basic family planning. “Mahirap madaming anak kung di mo kayang buhayin,” she whispered. (It’s difficult to have many children if you can’t support them.)

It was getting dark. Mercy hurriedly washed the pile of dirty laundry. She wanted to go home to feed her children. – Rappler.com

To know more about ACF, you may visit their website or Facebook. You can donate here.

How can we help alleviate hunger? Share your ideas with us. You can send articles, campaigns, commentaries, infographics, research and video materials to move.ph@rappler.com. Be part of the #HungerProject. Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.