Tucked away in Dinagat Islands are lush green forests teeming with endemic flora and wildlife, including the critically endangered Dinagat cloud rat previously believed to have been extinct. But because the island is also rich in nickel ore and chromite ore, it has been considered a mineral reserve for decades.

These attributes have long embroiled these islands in a delicate dance between economics and the fight for the conservation of biodiversity.

Since 2013, the provincial environment and natural resources office, along with local government units and advocates, have been pushing for the establishment and management of conservation sites in this area, as well as provision of sustainable livelihoods, in a bid to stem the tide of illegal logging and rampant mining operations in the province.

These conservation efforts, however, hit a wall when the coronavirus pandemic started to wade into Dinagat Islands’ territory.

As the province wrestled with the pandemic, it had put in place rigid quarantine measures and a massive lockdown to quell the spread of the virus.

These measures were even more strictly enforced when Dinagat was placed under enhanced community quarantine in April after Caraga region – of which the province is a part of – reported its first COVID-19 case.

The provincial environment and natural resources office, which primarily oversees the islands’ conservation efforts, had to shift to various alternative work arrangements.

This greatly affected field activities, including forest patrolling and field surveillance works, leaving Dinagat’s proposed conservation areas especially vulnerable to abuse. Forest protection personnel, for instance, worked in an on-call basis, relying only on text messages or calls from the Philippine National Police for reports.

With more people at home and quarantine restrictions impeding patrols in the area, the provincial environment and natural resources office (PENRO) has received not only reports of river and mountain quarrying during the outbreak, but also beach sand extraction.

These unsustainable practices have become rampant during the coronavirus quarantine, as people resort to these dire measures for income.

Hit by the outbreak

With the coronavirus pandemic continuing to pose major challenges, Dinagat’s conservation efforts have slowed down due to quarantine measures.

It was only in May when PENRO-Province of Dinagat Islands (PDI) was able to patrol the mangrove and mountain areas within proposed conservation areas in the province, apprehending about 1,073.5 board feet of illegally cut and undocumented lumber in various dimensions.

Dinagat’s conservation efforts also took a hit when PENRO-PDI’s annual budget was cut by 10% or about 2 million to provide additional funds for COVID-19 response. It has had to sacrifice several activities including the formulation of an integrated coastal management (ICM) and forest rehabilitation plan.

Too big a problem

The pandemic has highlighted the different threats to Dinagat Islands’ biodiversity.

Rich with resources, the province was declared a mineral reservation area through proclamation 391 by President Manuel Quezon in 1939.

Large-scale mining operations have scalped massive forests, and diluted nearby rivers and oceans, as well as watersheds in the province.

Locals in Dinagat’s Gibusong Island have forbidden the entry of any mining company after seeing the shore of neighboring barangays such as Esperanza turn brown because of spillover from mining operations, affecting corals, marine life, and the livelihood of residents.

These mining operations also encroach on possible conservation areas, with Dinagat Islands’ famous bonsai forest in the heart of Krominco Inc’s mining operations in Loreto.

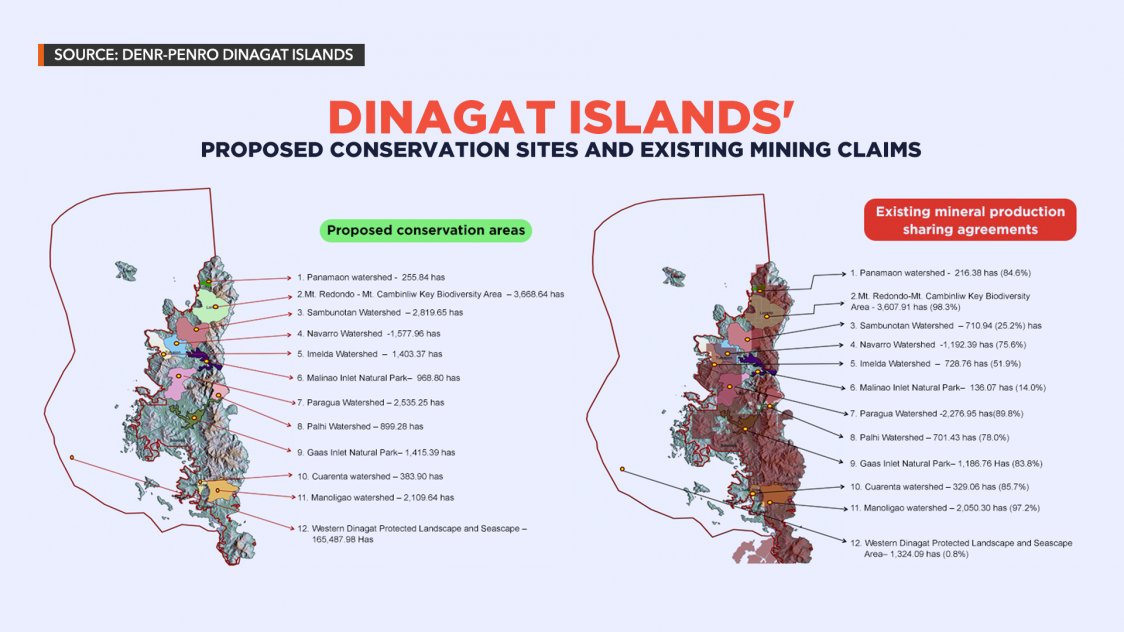

Dinagat Islands’ environment and natural resources office reported that there are at least 19 approved mineral production sharing agreements (MPSAs) and 3 joint operating agreements that have laid claim on more than half of the province’s land area. The mining claims cover 58,709.21 out of 80,212 hectares of Dinagat Islands’ land.

These threats to the province’s biodiversity have also contributed to Dinagat’s long-standing water shortage problem, which cuts across all 7 of its municipalities and is felt especially during El Niño and summer.

Because of this, prior to the pandemic, the PENRO-PDI had been working on getting congressional legislation to declare Dinagat’s priority watersheds, wetlands, and critical habitats as conservation areas and be excluded from the coverage of proclamation no. 391.

The declaration will help protect these areas from mining operations, as at least 14,461.04 hectares of the potential conservation areas overlap with current mining claims.

This has been one of the main goals of the Dinagat Islands Conservation Program (DICP) which was kickstarted in 2013 by then congresswoman Arlene Kaka Bag-ao, PENRO-PDI, and other stakeholders.

“’Yun ang challenge ng DICP kasi ‘yung mga identified conservation areas natin ay nasa loob ng MPSAs. Pero bakit kailangan natin talagang i-ensure ang protection ng ating mga watersheds? Precisely dahil sa tubig,” Rosalie Gonzaga, the chief of the conservation and development section of PENRO-Province of Dinagat Islands, explained to Rappler during its visit to the area in late February.

(That’s the challenge of DICP because our identified conservation areas are found within mineral production sharing agreements. But why is it important to secure to ensure the protection of our watersheds? Precisely because of water.)

She added that the conservation of watersheds could help respond to the pressing challenges faced by Dinagatnons such as food and water security, disaster risk reduction, and climate change mitigation.

These watersheds could help provide flood control and reduce soil erosion, especially when the province is prone to landslides due to its hilly features.

“Ito ‘yung kanyang serbisyo na nagpareduce ng vulnerability ng Dinagat Islands sa impacts ng climate change because Dinagat Islands ay isang island ecosystem, geographically located doon sa lugar na maraming typhoons,” Gonzaga added.

(This is its service in reducing the vulnerability of Dinagat Islands to the impacts of climate change because it’s an island ecosystem that’s geographically located in an area with many typhoons.)

Striking a balance

Apart from watersheds, the DICP is also pushing for the conservation of critical habitats and wildlife sanctuaries within these areas, some of which house endangered species.

These priority conservation areas cover 9 watersheds, namely, the Panamaon Watershed, Mt. Redondo-Mt Cambinliw Key Biodiversity Area, Sambunotan Watershed, Navarro Watershed, Imelda Watershed, Paragua Watershed, Palhi Watershed, Cuarenta Watershed, and the Manoligao Watershed.

Among the DICP’s projects is the establishment and management of the Western Dinagat Protected Landscapes and Seascapes, Malinao Inlet Natural Park, and Gaas Inlet Natural Park as protected areas under the Expanded National Integrated Protected Areas System.

According to PENRO, Dinagat is home to at least 100 bird species and 400 plant species. It also houses at least 20 globally threatened and Philippine threatened species of vertebrates listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

One of the largest in the country, swaths of natural bonsai forests spanning an estimated 1,000 hectares can also be found in the province.

Dinagat boasts of its own tarsier as well, confirmed by researchers as a species distinct from its relatives in other parts of the country.

Habitats for these species, however, may not survive for long as they find themselves in the thick of mining sites and encroaching areas with MPSAs.

This has pushed PENRO-PDI, as well as local communities and leaders, to think of ways to reduce dependence on mining through ecotourism and other sustainable livelihoods. Save for the pandemic, those areas, for example, can be prime spots for ecotourism and research tourism.

“Napakayaman ng Dinagat sa usaping kalikasan pero kung ang ating programa ay nakasentro lang doon sa destruction ng mga mineral resources, sayang lang din naman itong mga yaman ng kalikasan na napakaganda at napakadami na puwedeng gawin para sa development ng isla,” Dinagat PENR Officer Agapito Patubo told Rappler.

(Dinagat is so rich in natural resources. If our program is centered on destruction of mineral resources, we’ll be wasting nature’s wealth which we can use for the development of the island.)

For this to happen, Bag-ao believes the community must work hand in hand to shift away from making mining the norm. This includes making students and communities understand the importance of biodiversity, and doing workshops on livelihood they can do in conservation sites through the DICP.

In the end, the decision to conserve nature is up to the community.

Bag-ao told Rappler in February that she hopes Dinagat Islands would soon have strong people’s organizations that would eventually take a key role in deciding what’s best for the province – be it through mining, conservation, or a mix of both.

“Dungan sa duyog pud sa pagpalig-on sa advocacy for watershed development and enforcement of laws ang pag siguro na naay mga lig-on na people’s organization makigduyog sa pag decide sa unsay dangatan sa Dinagat,” she said.

(Strengthening our advocacy for watershed development and enforcement of laws should be paired with an assurance of strong people’s organizations that would join in deciding what’s best for Dinagat.)

While the push for ecotourism will have to be put on hold due to the pandemic, PENRO-PDI continues to find ways to empower communities to take up sustainable livelihood and learn more about conservation.

Although internet connection is hard to come by in the province, PENRO-PDI is eyeing to move its workshops online to continue its advocacy.

Seeing it firsthand

Worried about the state of their local watershed, a Dinagat town named Tubajon has even led a biodiversity conservation program in line with DICP.

Through the program, the local government gets to purchase seeds from those working from home for P10 each. These are to be planted in the Sambunotan Watershed, one of the priority conservation areas of the DICP situated within the Dinagat towns of Loreto and Tubajon.

It was also declared a local protected area of both towns, with elderly volunteers making it their mission to protect the watershed. However, it will need to be excluded from the coverage of proclamation 391 to make sure it won’t be mined by companies.

According to PENRO-PDI, mining claims cover 710.94 hectares of the Sambunotan Watershed. Aside from that, the watershed faces different threats such as timber poaching.

Although the community now seeks to protect the watershed, they initially did not understand its importance. Prior to the pandemic, it had taken a series of forums – explaining how the conservation of the Sambunotan Watershed can help the people of Tubajon – to change their minds.

To bring in more funds in light of DICP’s budget cut, the local government of Tubajon has, so far, offered to shoulder the expenses for the workshops needed to make the ICM and forest rehabilitation plan.

For Tubajon Mayor Simplicia Pedrablanca, the push for conservation is needed in the face of widespread environmental degradation from mining, especially for a province that relies heavily on farming and fishing for livelihood.

“So kung maging wala ‘yan, lalo kaming maging mahirap dahil 5th class municipality kami,” Pedrablanca told Rappler. (If we don’t have livelihood, we will be even poorer because we’re a 5th-class municipality.)

With the Sambunotan Watershed’s declaration as a conservation area still in the works, Pedrablanca said Dinagatnons can already feel the impact of mining in the area.

“Lalo na dito sa amin, mataas ang dry season. May [scarcity] when it comes to water because nakita namin ang forest, especially the watershed ‘yung Sambunotan, ay hindi na gaano ka maayos. Kaya hindi na niya kaya ibigay ‘yung pangangailangan ng household when it comes to water distribution,” she said.

(It gets particularly intense during the dry season. There’s scarcity of water because we saw the forest, especially the Sambunotan Watershed, is struggling. That’s why it can no longer address the needs of the household when it comes to water distribution.)

The work continues

While PENRO-PDI can travel with ease now that quarantine rules have been relaxed, the Dinagat Islands Conservation Project still had to discontinue the formulation of ICM and forest rehabilitation plan; and meetings of the Protected Area Management Board, Provincial Cave Committee, and Multi-sectoral Forest Protection Committee (MFPC), among others.

The MFPC meetings are especially important as issues and concerns related to environmental problems in the province are tackled by representatives from different groups, including the Philippine National Police, Philippine Coast Guard, Bureau of Fire Protection, academe, religious organizations, and the private sector.

However, the push for the declaration of conservation areas continues as PENRO-PDI finalizes the profiles of at least 9 watersheds throughout the provinces, including 3 proposed protected areas that are considered initial components of the National Integrated Protected Areas System (NIPAS).

“It is more of a challenge than a problem. We just have to find ways to get things done in this time of crisis. There will be delays as we are still trying to adjust to the ‘new normal’ but still our goals and objectives are the same, only that, we will be changing our strategies to meet them,” said Patubo.

The profiles of the proposed conservation areas will be presented to Dinagat Representative Alan Ecleo and Association of Philippine Electric Cooperatives Representative Sergio Dagooc for the possible filing of the appropriate bill in Congress.

Despite the pandemic, Dinagat hopes that more conservation areas will be established as it moves to turn the island province from a mining reserve into an environmental haven. – Rappler.com

This story is produced in partnership with Friedrich Naumann Foundation.

How does this make you feel?