SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – “The hearing will begin in one minute.”

When the House committee on justice convened again to determine probable cause in an impeachment complaint against Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno, its chairman spent a huge chunk of his opening remarks to “emphasize the significance of the proceedings” and “clarify issues that were raised” as his committee ventured where none of its predecessors had even been.

Amid allegations of the committee being biased against Sereno and haphazard in its previous hearings, Oriental Mindoro 2nd District Representative Reynaldo Umali was firm: We’re just doing our job. (READ: Alvarez defends Sereno impeachment hearing: We’re looking for the truth)

“The responsibility of ensuring that the highest officials of our government remain accountable and competent to serve their position rests with the committee on justice, which I would like to call the impeachment committee, through the extraordinary power of impeachment,” said the legislator, citing Section 3, Article XI of the Constitution.

It’s an argument Umali and other top officials in the House have raised time and time again, as criticisms mount, particularly in the context of the Sereno impeachment.

But the “extraordinary power of impeachment” is one that’s been wielded – or at least, attempted to be wielded – several times against at least 5 of the country’s top officials, in 2017 alone.

Is the “extraordinary power” still extraordinary?

5 impeachments, only two stand

House Secretary General Cesar Pareja, in 2017, has had to receive and in several instances, process several impeachment complaints this year. These include:

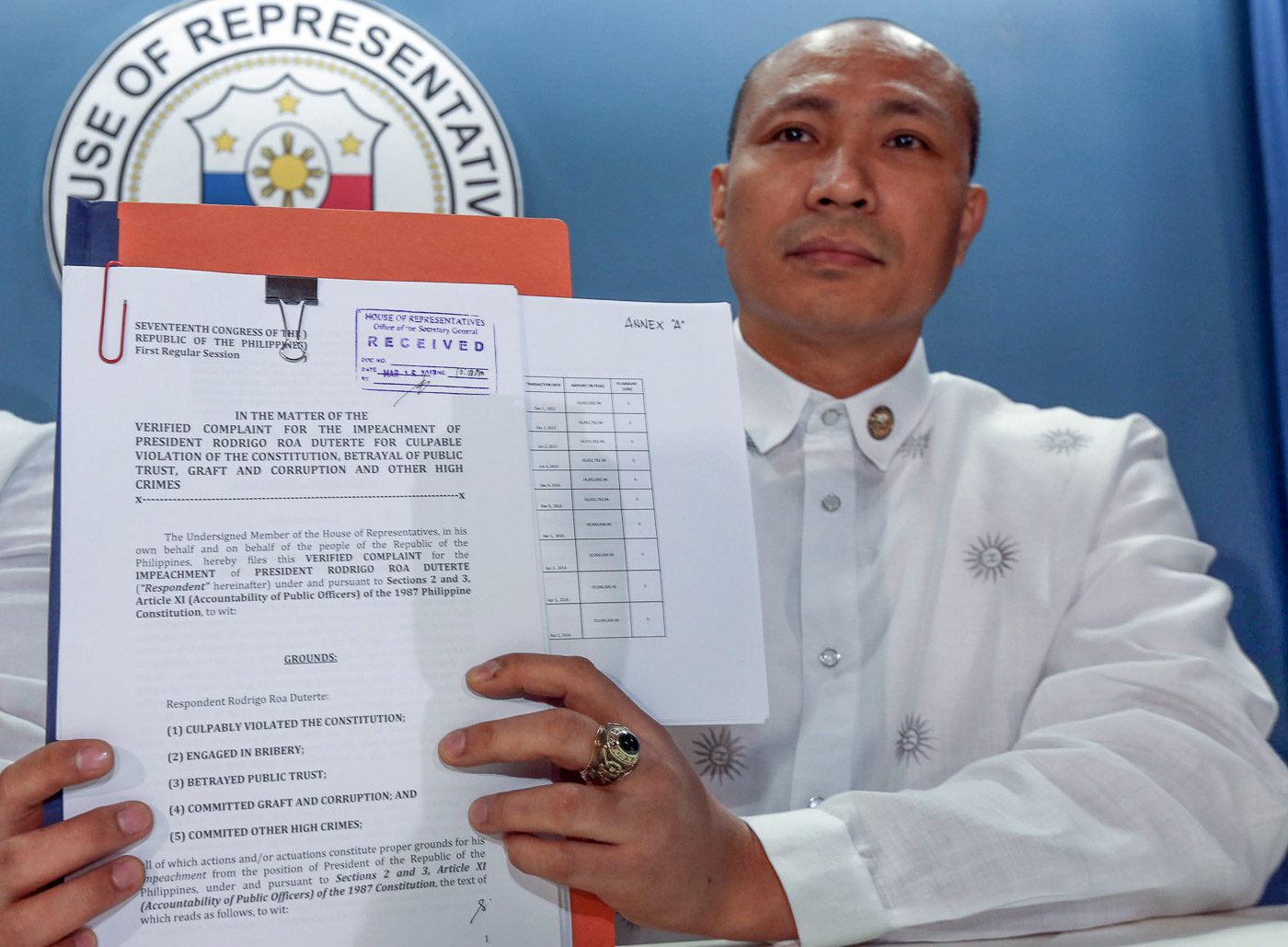

- A case against President Rodrigo Duterte, filed by Magdalo Representative Gary Alejano on March 16;

- In March, House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez himself said he was mulling a case against Vice President Leni Robredo. In May 2017, a group of Duterte supporters said they would file an impeachment case, pending endorsements from legislators;

- The Volunteers Against Crime and Corruption (VACC) and the Vanguard of the Philippine Constitution, Incorporated (VPCI) “filed” an impeachment case against Sereno in early August, but got no endorsers

- In late August 2017, 3 legislators, including two ranking members, endorsed an impeachment complaint against Commission on Elections Chairman Andres Bautista;

- On August 30, lawyer Larry Gadon filed an impeachment case against Sereno with the endorsement of 25 legislators;

- Sixteen members of the House eventually endorse the VACC and Vanguards impeachment complaint against Sereno so it is deemed filed;

- Just before session ends for 2017, the VACC “files” an impeachment complaint against Ombudsman Conchita Carpio Morales but gets no endorsers

We use quotation marks in describing the status of the early August 2017 complaint against Sereno and the complaint against Morales because under House rules, an impeachment complaint from a non-House member is only deemed filed if it has the endorsement of at least one legislator.

“These impeachment cases, practically they’ve become a dime a dozen, haven’t they?” said Akbayan Representative Tom Villarin, a member of the “Magnificent 7,” an independent bloc of legislators who are part of the small House opposition.

Of those filed, or threatened to be filed, 4 reached the committee on justice, which is tasked to tackle impeachment complaints.

Two – the Duterte and Bautista complaints – were sacked right away for being insufficient in either form and substance.

But the House overturned the committee’s decision in the Bautista complaint, impeaching him just before Congress took a break in October.

Bautista’s resignation – which was supposed to be effective on December 31 yet – was deemed accepted by Duterte immediately. His case did not reach the Senate.

The Duterte impeachment case was deemed sufficient in form, but not in substance, After over 4 hours of deliberation, it was rejected by the committee. (READ: It takes only a day to kill an impeachment complaint vs Duterte)

It’s the Sereno impeachment case that’s made it the farthest.

Although the committee junked the VACC and Vanguards complaint for being insufficient in form, it is currently deliberating probable cause – the last step before it does a final vote – in the Gadon impeachment.

For Villarin, the pattern of how the House and the committee, in particular, has handled the various impeachment cases makes it clear that there’s a “state of confusion.”

“When the complaint is against the President, there was the immediate reaction to dismiss. When the impeachment cases against those critical [of the administration] came, suddenly the House became so very open to entertain such questions. It’s like saying that if it’s an impeachment against those who are critical against the president, the House has time to hear these cases,” added Villarin.

The last resort

Under the Constitution, only the President, Vice President, Supreme Court justices, members of the constitutional commissions, and the Ombudsman may be removed from office via impeachment.

The grounds for impeachment are the “culpable violation of the Constitution, treason, bribery, graft and corruption, other high crimes, or betrayal of public trust.”

Article XI of the Constitution also reaffirms the role of the anti-graft court Sandiganbayan and spells out the duties of the Ombudsman in holding public officials accountable.

Law professor Tony La Viña says this means impeachment is “supposed to be only used for very extraordinary reasons.” “The main thing is that I think we’ve bastardized [the] impeachment [option],” he told Rappler in a phone interview.

La Viña pointed out that in the case of Robredo, her critics wanted her out for “essentially giving a speech.” In the Sereno case, La Viña said, the charges seem to be administrative lapses that are not impeachable.

While he concedes that the points raised in the Alejano complaint against Duterte were “serious charges,” he doesn’t think all options have been exhausted.

“You have to exhaust all options. Impeachment is not a replacement of politics, and that’s what’s the problem here,” he added.

During its last hearing on the Sereno complaint for 2017, the House committee on justice was the setting of a rather unusual event: Supreme Court (SC) associate justices, both retired and incumbent, publicly lashed out at their “primus inter pares,” the Chief Justice. (READ: Justices on Sereno ‘transgressions’: Until when will we suffer?)

Umali said the committee needs to ultimately decide if Sereno is still fit for the job.

This means they’ll definitely take into consideration the grievances her colleagues in the High Court have brought up. (READ: Impeachment committee question: Is Sereno still fit to hold office?)

Former Supreme Court associate justice Arturo Brion, as he talked about Sereno’s apparent pattern in disregarding the collegiality of the Supreme Court when she made her decisions, said it was hard to hold her accountable.

La Viña disagreed. “Time and time again, [Sereno] has lost votes. Time and time again, they (the Supreme Court en banc), have reversed her,” he said.

In a lot of big cases, Sereno has found herself in the minority. (READ: ‘Do not be afraid to be minority’: Chief Justice Sereno, 5 years on)

Villarin said that although transparency is important, even in the usually secretive Supreme Court, it could also be abused.

“Now, you’re opening a situation wherein the bickering among justices and even the deliberations are out in the open. It also reflects how that mechanism, in a way, has failed,” said Villarin.

Aside from exposing the Supreme Court’s weaknesses, La Viña said the impeachment process – or at least the Sereno case – has made the House “very powerful.”

“That’s not necessarily good because at some point, they could overreach and the country will be in trouble. If [for example], they issue a warrant against Sereno and she doesn’t appear, that could be very serious [and have] long term consequences on the judiciary. Definitely the judiciary has been severely weakened by this episode,” he noted.

It’s not the first time the legislative branch (and, in some ways, the executive) has been accused of weakening the judiciary.

In December 2011, the House, then dominated by an LP-led majority, impeached Renato Corona as chief justice. (READ: Corona found guilty, removed from office)

But that complaint did not go through the scrutiny of the House justice committee, since it was signed by at least one-third of the House. It went straight to the Senate, which eventually convicted him for his failure to disclose his assets properly.

Despite comparisons by many, La Viña thinks the Sereno and Corona impeachments are “very different.” (READ: How similar are the Sereno and Corona impeachment cases?)

But aside from the process and allegations made against the two chief justices, they do share something in common: the apparent approval of the president.

A powerful executive

The nearly 300-strong House of Representatives is dominated by PDP-Laban, which Duterte ran under in 2016. Different parties are groups are part of the “supermajority,” including the Liberal Party (LP). (READ: The fall of the ‘dilawang’ Liberal Party)

Despite the “confusion” that impeachment cases may elicit, Villarin said one thing is clear: “When the speaker says this is it, then the House really obeys.” (READ: A year later, the House remains Duterte’s loyal defender)

La Viña said if the impeachments – both in the previous and current administrations – have taught us anything, it’s that they only work if the President “gets involved.”

Former president Benigno Aquino III made no secret of his disdain for Corona and neither has Duterte of his disdain for Sereno.

Corona was an appointee of Aquino’s predecessor, former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. Sereno is an Aquino appointee.

“The president… will use all his power in Congress to make sure that they will never get the votes against him. The corollary is also true. If the President wants a person impeached he can make it happen even if there may be no basis. There has to be a signal, I think from the President,” said La Viña.

Just like Duterte, the impeachment complaint filed against Aquino back then was also quickly junked. Their allies have also seemingly toed the line when it comes to impeachment threats against other officials.

Duterte shot down the impeachment threat against Robredo. Aquino did not publicly support threats to impeach former vice president Jejomar Binay, despite an ongoing Senate probe then into allegations of corruption, spearheaded by no less than Aquino’s allies.

Impeachment is one of many processes under Philippine law that people can take to make sure those in power – may they be elected or appointed – have those powers checked.

But there’s a caveat.

“We need to rethink our concept of impeachment, as the ultimate way of holding a person responsible. If it’s gonna be used like this, for politics, right? Never mind,” said La Viña.

The House committee on justice or the “impeachment committee,” as Umali himself puts it, is set to vote on probable cause in the complaint when Congress resumes in January 2018.

While Umali makes it a point to say that he doesn’t want to “pre-empt” the committee vote, if Alvarez’ public statements are to be believed, all signs point to impeachment. (READ: Probable cause in Sereno complaint? ‘Sobra-sobra,’ says Alvarez)

It is a process used to its full potential or one that’s being abused?

The 50-or-so members of the impeachment committee will have to chew on that thought over the holidays. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.