SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

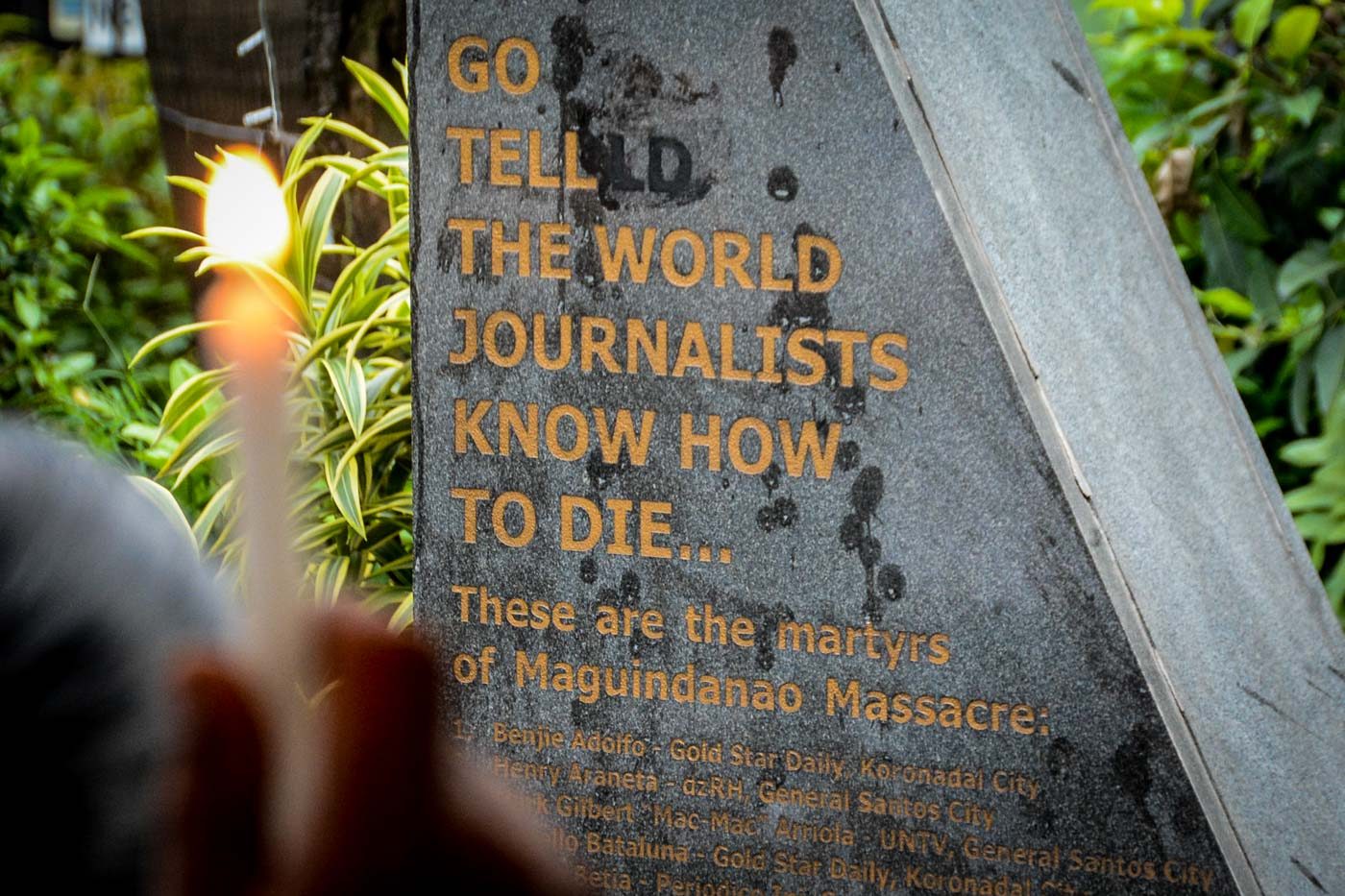

CAGAYAN DE ORO, Philippines – Fourteen years ago, November 23, 2009, a convoy of 58 people – 32 of whom were media workers – were waylaid by armed men as they headed to the provincial Commission on Elections (Comelec) office in Shariff Aguak for the filing of the certificate of candidacy for Maguindanao governor of Ismael Mangudadatu, then the vice mayor of Buluan town.

The armed group belonged to the local political dynasty of then-governor Andal Ampatuan Sr. whose son and namesake, Andal Jr., was running for Maguindanao’s top post.

In 2009, Ampatuan town was part of the bigger Maguindanao, a province that was subsequently split into two by a law that was ratified in September 2022.

The massacre horrified the nation and highlighted numerous issues that had been known but not addressed for a long time.

On one hand, the incident served as a grisly wake-up call for both national government and local and international civil societies on the issues of election violence, clan politics and dynamics, and violence against the media. On the other hand, it gave journalists a more critical look at safety and security issues when covering election-related events and paved a collective call for an end to the culture of impunity.

Invited to cover

JB Deveza, former editor-in-chief of the now defunct Sunstar-Cagayan de Oro, told Rappler on Wednesday, November 22, that he, along with other journalists, nearly joined in covering the filing of Mangudadatu’s certificate of candidacy.

Deveza was with a group near the area covering the second “State of the Bakwit” (internally displaced persons or IDPs), organized by the group Bantay Ceasefire. The activity was aimed at looking at the state of IDPs in conflict areas in Maguindanao and Cotabato provinces.

While in Datu Piang town, Deveza recalled that journalists were asked if they were interested in covering the filing of Mangudadatu’s COC.

“The group already stayed there for at least a week. So, most of us [were tired and] decided to go back to our homes,” Deveza said.

Another journalist who covered the State of the Bakwit, Charlie Saceda, said he decided to forego covering Mangudadatu’s COC filing.

“We could not believe that it could happen. The number of deaths was so huge that it bordered on bad gossip,” said Saceda who was then the projects coordinator of the Cebu-based Peace and Conflict Journalists Network (Pecojon).

Safety awareness

Now serving as the program and safety officer of InterNews, Saceda said the Ampatuan massacre made him more determined to promote safety among journalists.

Since the massacre, “I have been more invested in journalist safety and always advocated for the community’s understanding of the role of the media because the community will be the journalists’ first line of defense,” said Saceda.

Veteran journalist Froilan Gallardo recalled the first time he learned about what happened in Maguindanao. He said he was in Zamboanga where he was invited to speak during a news photo exhibit.

“After my talk, some of the staff at the Ateneo de Zamboanga told me that several journalists were missing in Maguindanao. The reports were (still) sketchy at that time,” Gallardo recalled.

After an hour, he said he called up fellow journalist Dennis Jay Santos in Davao City, who told him that more than a dozen journalists who joined the Mangudadatu convoy were “missing.”

“Knowing the political rivalry between the Ampatuans and Mangundadatu, I realized this was serious,” Gallardo said.

After the killings were confirmed, “We all decided to go to Sharif Aguak which was a difficult decision to make since many were worried that the Ampatuans would go on a killing spree against journalists who will come to cover the (aftermath of the) massacre,” he recalled.

He said he and other journalists moved from one inn to another in the area and always gathered for planning and briefing before going out to the massacre site.

Gallardo said the Ampatuan massacre increased his and many other journalists’ awareness of safety and underscored the importance of thorough planning when doing on-field news coverage.

Among the very first journalists on the scene of the massacre, Dennis Jay Santos said he couldn’t believe what he saw.

“I’ve been to a lot of crime scenes in my journalism career but nothing can compare with what I saw as I walked closer to the area. [It was the] darkest night for Philippine journalism for me. Surely, the architect of this dastardly act has no sense of humanity and place in our civilized modern world. They ought to rot in jail,” he told Rappler.

As of posting time, only 44 of the nearly 200 massacre suspects have been convicted. This includes 28 members of the Ampatuan political dynasty and others primarily accused in the gruesome attack. Currently, 83 suspects remain at large. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.