SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Former poll chief Sixto Brillantes Jr criticized the Commission on Elections (Comelec) for including an “unconstitutional” question in certificates of candidacy (COCs), which could make convicted individuals “disqualify themselves” even without a final court judgment.

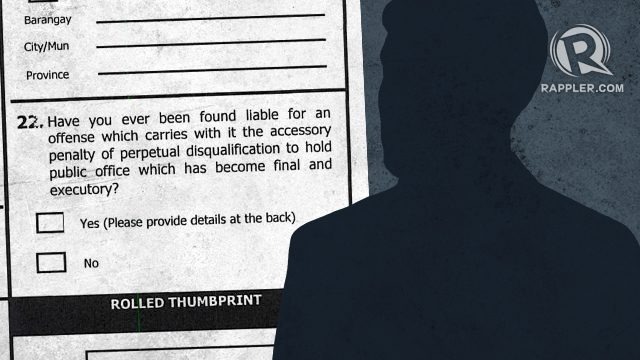

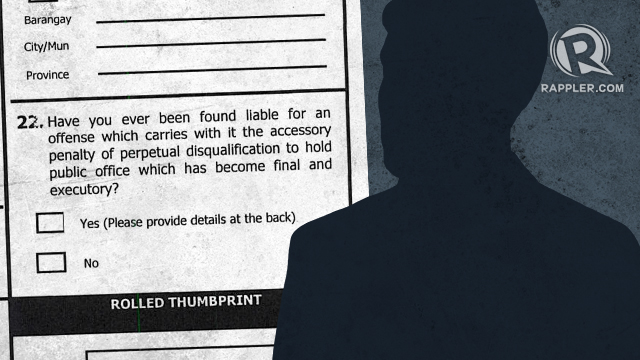

The new question in the COCs is, “Have you ever been found liable for an offense which carries with it the accessory penalty of perpetual disqualification to hold public office which has become final and executory?”

By answering “yes” to question 22, Brillantes said a candidate can unwittingly disqualify himself or herself from the get-go. “‘Pag nilagay mong ‘yes,’ eh ‘di disqualified ka na. Para mo nang dinisqualify ang sarili mo (If you put ‘yes,’ then you’re disqualified. It’s like you disqualified yourself).”

“This is unconstitutional,” Brillantes told Rappler on Thursday, referring to the new question in the COCs. “Hindi naman requirement ito in order to run eh. Ang qualification mo to run ay nasa Constitution ‘yan (That is not a requirement in order to run. The qualifications to run can be found in the Constitution).”

For the position of senator, for example, the set of qualifications under the 1987 Constitution is basic: One should be a natural-born Filipino, at least 35 years old on election day, able to read and write, a registered voter, and a resident of the Philippines for at least two years.

Brillantes stressed that accepting COCs is ministerial on the part of the Comelec.

“Kung qualified ka, puwede ka nang mag-file ng certificate of candidacy. Hindi ka naman puwedeng tanungin, ikaw ba may pending kaso ka rito? Anong status ng kaso mo? Final na ba ‘yan o executory?” he said.

(If you’re qualified, you can file a certificate of candidacy. They cannot ask you, do you have a pending case here? What is the status of your case? Is that final or executory?)

Brillantes said that “final and executory,” in the first place, is debatable even for lawyers.

Brillantes also said a non-lawyer candidate does not normally understand the nuances of a question like this. “What offense? Administrative, criminal? Involving an accessory penalty of perpetual disqualification? What do we mean by accessory? What do we mean by accessory penalty? What is a final and executory judgment?” he said in a mix of English and Filipino.

Brillantes: Just say no

Brillantes, one of the Philippines’ most seasoned election lawyers, advised candidates to just answer “no” to this new COC question, or leave the question blank. Will this make a candidate possibly liable for perjury? No, Brillantes said, because the candidate can always say he or she didn’t understand the question.

(Check a sample COC for senator below.)

Brillantes said the new question in the COC can affect many candidates, including those dismissed by the Office of the Ombudsman in administrative proceedings.

“Kapag dinismiss ka ng Ombudsman in administrative proceedings, disqualified ka under the Omnibus Election Code, sa local government. Isipin mo ‘yon, kapag meron kang dismissal, eh naka-motion for reconsideration ka pa lang, o nasa Court of Appeals ka. Ano ba ‘yan, final and executory na ba ‘yan? Eh ang desisyon ng Ombudsman under the law is immediately executory. Eh final na ba ‘yan? ‘Yan ang tanong,” said the former elections chief.

(If you’re dismissed by the Ombudsman in administrative proceedings, you’re disqualified under the Omnibus Election Code, for local governments. Imagine that, if you have a dismissal, and you have a pending motion for reconsideration, or you’re still at the Court of Appeals. Is that already final and executory? But the decision of the Ombudsman under the law is immediately executory. Is that final? That’s the question.)

“The right to aspire for public office is a constitutional right,” Brillantes pointed out. “You cannot impose conditions, you cannot disqualify, without due process, for as long as they have all the qualifications. If they are disqualified, then prove the disqualification. Not by forcing them to admit in the COC.”

Sought for comment on Brillantes’ criticism, Comelec Spokesperson James Jimenez said on Thursday evening that the poll body was still studying the matter.

‘Unduly’ expanding Comelec’s power

Election lawyer Emilio Marañon, partner at Trojillo Ansaldo & Marañon Law Offices, also criticized question 22 in the new COC template.

In a Facebook post, Marañon said that “this is exactly the problem” with “overly expanding the contents of the certificate of candidacy (COC) beyond the minimum set in Section 74 of the Omnibus Election Code.”

“Can this even be done by a mere administrative issuance?” he asked.

For the COC, Section 74 of the Omnibus Election Code only requires information such as the person’s political party, civil status, date of birth, residence, and post office address, as well as general statements such as support for the Constitution and obedience to the law. There is no requirement to categorically state in the COC if one has been disqualified by final judgment or not.

Marañon said the additional declaration in the COC blurs the lines between the different ways of questioning or attacking the candidacy of a candidate before elections.

In a 2016 piece for Rappler, Marañon explained the two ways by which a candidate can be eliminated from an electoral race before elections: a “petition to deny due course” and a “petition for disqualification.”

A petition to deny due course concerns a person’s COC. Marañon said the Comelec can cancel a COC only if there is “misrepresentation directly touching on eligibility,” such as one’s qualifications. The Comelec can deny due course to a COC if, for example, the candidate deliberately lied about his or her citizenship to become eligible.

A petition for disqualification goes beyond a COC. It is a mechanism to inquire whether a candidate committed any of the grounds disqualifying him or her from running, even if the candidate has satisfied all the minimum qualifications.

Thus, if a candidate is indeed perpetually disqualified because of a court judgement, Marañon said that this “is rather covered by a petition for disqualification.”

“Obviously, the intention is to put any and all kind of ‘misdeclaration/s’ under the coverage of the deny due course petition, which is wrong and theoretically off. Under Section 78 of the OEC, only misrepresentation directly touching on eligibility (i.e. qualification) can be made subject of a deny due course petition. The question relating to the accessory penalty of perpetual disqualification is rather covered by a petition for disqualification, not by a deny due course petition,” Marañon said.

“The new move of Comelec will not only unduly expand its power over candidates beyond what is sanctioned by law, but will dangerously blur the delineations of the petitions to deny due course, disqualification and post-election quo warranto,” the election lawyer added.

The filing of COCs is scheduled from October 11 to 12, and 15 to 17.

The contentious question in the COC follows another controversial rule initially made by the Comelec and also criticized by Brillantes. The initial rule allowed the substitution of candidates who withdrew from the elections until midday of election day.

After criticism, the Comelec amended this rule, and limited substitution due to withdrawal only until November 29. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.