SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

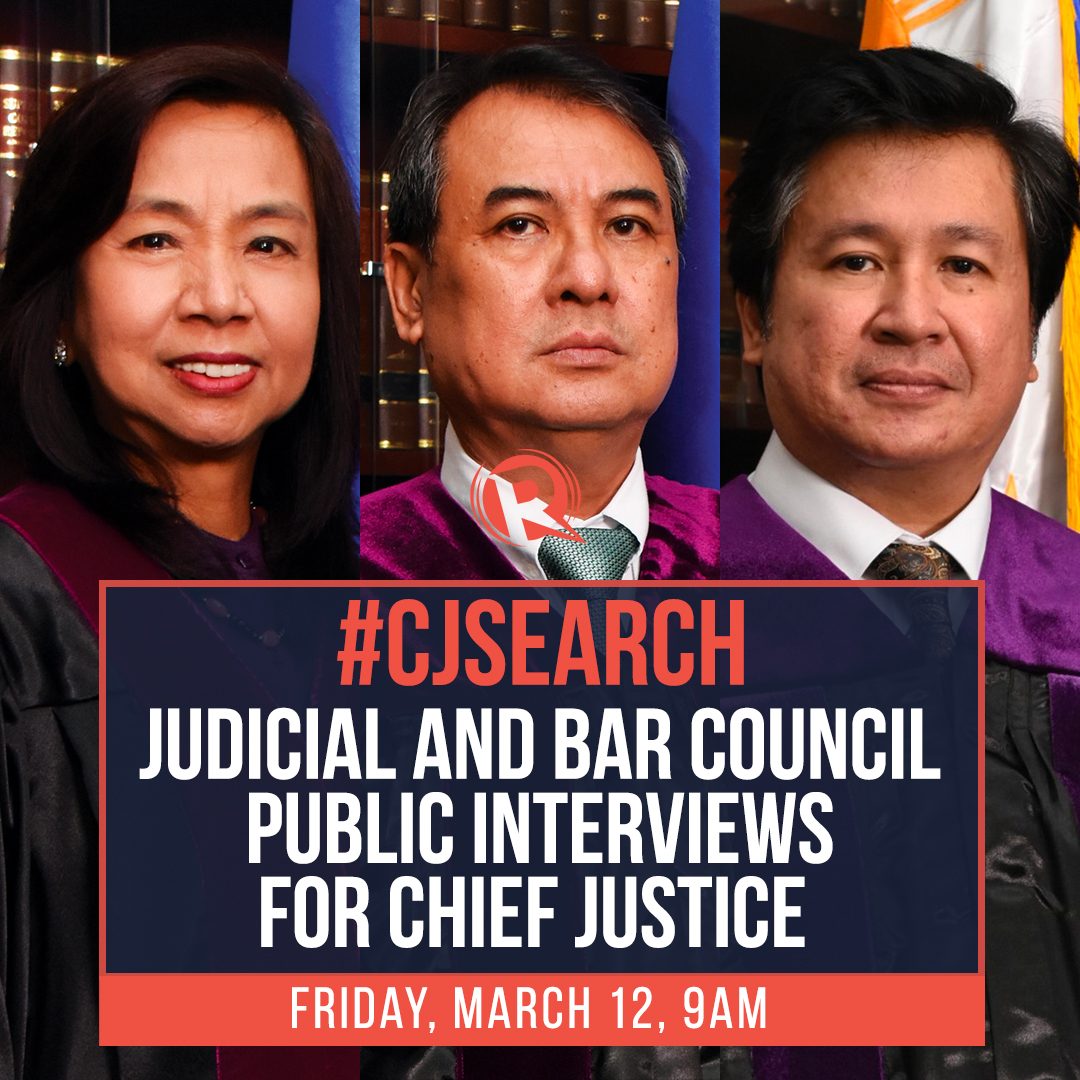

The Judicial and Bar Council (JBC) will flesh out the judicial principles of the 3 magistrates applying for chief justice when they undergo public interviews on Friday, March 12.

The interviews will provide a glimpse into where they stand on issues surrounding the judiciary. Lawyers have called on the JBC not to skirt pressing issues and to ask the applicants about President Rodrigo Duterte’s dismissive attitude toward human rights.

If past interviews are any indication, the JBC will likely ask applicants Senior Associate Justice Estela Perlas-Bernabe, Associate Justice Alexander Gesmundo, and Associate Justice Ramon Paul Hernando whether they side with judicial activism or judicial restraint.

Judicial activism is a principle where the Supreme Court does not back down from reversing actions of its co-equal branches, the executive and Congress, if it finds those to be unconstitutional.

Judicial restraint is a tendency to step aside and let the executive and Congress do their job following their own discretion, believing that the will of the people must be respected by respecting the actions of those they elected.

Former chief justice Lucas Bersamin had gone on record to say he’s in favor of restraint, while statements of Chief Justice Diosdado Peralta indicate the same preference for restraint. They are Duterte’s last two chief justice appointees.

The recent spate of killings and human rights abuses have prompted calls for the Supreme Court to be more proactive, pushing it to the side of activism.

(The following review of the chief justice applicants’ judicial principles is arranged based on their seniority.)

Bernabe as the textualist

Comparing voting history would be difficult since Gesmundo and Hernando are new. But based on their voting patterns under Duterte, Gesmundo and Hernando have consistently voted in favor of the President’s interests.

Bernabe also mostly concurred with the majority that handed wins to the President, like the decisions that upheld martial law in Mindanao.

Bernabe had been on the dissenting group a couple of times, most notably when she dissented in the close ruling that ousted Sereno, and the similarly close ruling that upheld the drug charges against Senator Leila de Lima.

In these cases, she joined the so-called constitutionalist bloc of the bench, alongside the likes of retired justice Antonio Carpio and Justices Marvic Leonen and Benjamin Caguioa – two of her fellow Aquino appointees who opted out of the race.

Bernabe, though, has proven to be unpredictable on the bench, making nuanced votes like in the Mindanao martial law decisions where she concurred only in the result, but dissented to the doctrine that says the president has unbridled discretion in declaring military rule.

Bernabe is a self-acclaimed textualist – or a jurist who is very faithful to what the text of the law says.

“I’m a bit of a textualist. But if the law is not clear, and I would have to uncover its intent, then the task of uncovering the intent would be based on reason, logic, practical impact on society, and sometimes even the practicality of the times,” Bernabe said in her chief justice interview in 2019, a round where Peralta got the appointment.

As a textualist, Bernabe’s interpellations during the anti-terror law oral arguments mostly required petitioners to cite case laws pertaining to Congress’ discretion and the political issue doctrine. (The political issue doctrine involves the Supreme Court leaving an issue alone because it is best left to the discretion of the political branches.)

Bernabe’s most memorable ponencias were those that declared the pork barrel unconstitutional and the decision that struck down the condonation doctrine – a favorite doctrine of politicians because it used to allow them a way out of corruption charges if they were reelected.

Gesmundo and Hernando

Gesmundo’s recently noted ponencia was the decision that allowed foreign construction firms to have regular contractor licenses, a win for the Philippine Competition Commission (PCC), which wanted to reap economic benefits from opening up the industry to foreigners.

Gesmundo was also the ponente of the decision that denied the legal challenge to Duterte’s Bayanihan Law 1, one of the President’s 3 wins during the pandemic when the Supreme Court made many other petitioners wait. (The two other wins were the junking of petitions to disclose Duterte’s state of health and compelling the government to conduct mass testing.)

At the anti-terror law oral arguments, Gesmundo pursued a line of questioning that tended to agree with the government that there are existing safeguards to potential abuses.

For one, Gesmundo said an abusive law enforcer can always be sued for damages under the Civil Code. Gesmundo also said that the law can’t be struck for being too vague when all suspects are afforded the right to clarify charges during trial.

Hernando, on the other hand, was the ponente in the decision that fined water firms for not putting up sewerage lines, a ruling seen as pro-environment. Hernando also wrote the decision that granted full benefits to the widow of the late former chief justice Renato Corona, saying that Statements of Assets, Liabilities, and Net Worth (SALN) should not be weaponized.

Hernando also showed his progressive side in the still pending case of an illegitimate child’s inheritance rights. Hernando said during oral arguments that the Civil Code provision that distinguishes “legitimate” from “illegitimate” children was “backward.”

At the anti-terror law oral arguments, Hernando’s line of questioning tended to temper petitioners’ fears that the arrest and detention provisions of the law were too harsh, saying that terrorism was an extraordinary crime “where police would need to dig deeper.”

Hernando also said during oral arguments that designation as a terrorist under the law is nothing to be feared because it would just freeze assets, and not be an authority to arrest. Petitioners had disputed this, saying the wording of the law would inevitably make designation a prelude to arrest.

Watch the JBC interviews on Friday, starting at 9 am. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.