SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – How much budget does a police station need to keep operations in full steam and be able to respond quickly to law enforcement necessities?

There are no hard and fast rules. A police station in Patikul, Sulu will have different operational needs compared to a station located in the heart of Makati City.

Interior and Local Government Secretary Jesse Robredo believes, however, that for every policeman assigned to a station, the unit should get at least P1,000 a month for maintenance and other operating expenditures.

And he has asked Congress to stipulate this new distribution formula in a special provision in the budget of the Philippine National Police (PNP) for 2011.

Robredo’s proposal made it to the final version of the 2011 national budget. Thus, once operational guidelines are finalized, a police station which has 30 policemen assigned to it, should expect to receive at least P30,000 every month for electricity, fuel, transportation, mobile and landline communications, and other office and operational necessities.

Funding field units

It’s a 56-percent increase from the amount the field units are supposed to be receiving the previous year. As of June 2010, the distribution was about P640 per police officer per month, according to Robredo.

If you take into consideration everything that a policeman in the field will need to respond to calls for help, shoot bad guys, call for back-up when necessary and investigate crimes, the fresh funds infusion are still clearly not enough.

If you spend half of the entire sum on fuel alone, that would mean that the station would have a budget of P500 a day to keep its vehicles running and ready to respond to peace and order emergencies.

Not all cops are equipped with two-way radios—which could cost as much as P80,000 per unit. To enable policemen to communicate, the station would probably need to subsidize the mobile phone load of its people.

A modest mobile phone allowance of P350 per police officer—equivalent to the cheapest unlimited call service in the market at the moment—would mean a total of P10,500 for a 30-man police station.

The PNP’s bigger budget this year is still not enough, but it gives field units some breathing space.

This leaves the station with only about P4,500 for electricity, a landline (for receiving calls for police assistance from the public), office supplies and other contingencies.

Still, this won’t be enough. But it is significantly more than what field units have been getting in the past.

Some police stations have been receiving as little as P500 a month from the PNP’s budget for maintenance and operating expenditures, according to a source from the budget department who is privy to the matter.

Consequently, most police units have been dependent on the generosity and support of local chief executives to augment ridiculously meager funds and support operations.

This is well and good if the mayor or governor is an exemplar of good behavior. The Maguindanao massacre, however, has amply illustrated problems that could arise if the local police is beholden to local powers.

Crame’s share

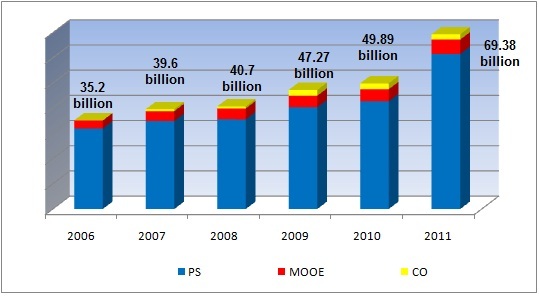

At roughly P69.38 billion, the PNP’s budget for 2011 is almost double its level half a decade ago. (See Table 1: The PNP’s budget from 2006 to 2011)

The budget composition, however, remains almost the same. (See: A series of unfortunate events.) Almost 89 percent (roughly P61.55 billion) of the total sum still goes to salaries, wages and other personnel benefits.

The budget for 2011 increased by about P20 billion compared to the previous year. It is the biggest increase the police establishment has had in the past half decade. But bulk of the fresh funds will go to salary increases mandated by the salary standardization law as well as for hiring 10,000 new personnel.

Less than 1/10th of (only about 8.25 percent) of the total budget goes to maintenance and other operating expenditures. This includes funding for training, purchase of ammunition, telephone communications, fuel, fuel, electricity, travel and office supplies.

Even more minute is the portion of the budget intended for capital outlay, which the PNP needs in order to buy guns, upgrade equipment, modernize its operations as well as put up police stations and headquarters.

Ping’s legacy

Increased funding is not the only solution to the problem, according to analysts who studied the PNP’s use of its resources said.

Part of the problem, they said, is the fact that headquarters hogs the lion’s share of meager resources. Consequently, very little trickle down to the field units where they are most needed.

Over a decade ago, when he was PNP chief, Panfilo Lacson implemented a policy which prescribed that only 15 percent of police personnel should be assigned to the various headquarters while 85 percent are supposed to be assigned to police stations and other field units.

Lacson also had funds for maintenance and other operating expenditures distributed following the same ratio.

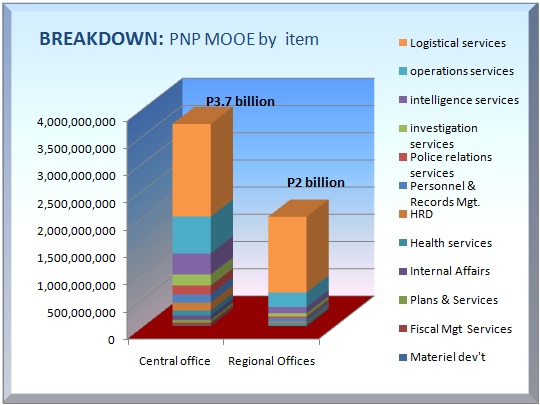

That policy remains in place up to now, according to Senior Supt. Joevic Ramos of the PNP Directorate for Comptrollership. But this distribution formula is not evident if you look at the budget of the police establishment. (See Table 2: Breakdown of the PNP’s MOOE for 2011)

Total MOOE for this year is P5.71 billion—up by almost a billion from P4.8 billion in 2010.

If you strictly follow the avowed policy, then 85 percent of that amount—or about P4.86 billion—should go to the field units. That is not the case at all.

Newsbreak’s analysis of the line items in the PNP’s budget shows that bulk of the funds—about P3.7 billion—for maintenance and other operating expenditures is still controlled by the PNP’s headquarters in Camp Crame. Only about P2 billion of the amount are released directly to the regions.

Partly this is because funds for some units, such as the Crime Laboratory, are initially disbursed to mother units quartered in Crame. In the case of the Crime Laboratory, the funds are eventually shared with field units involved in scene of the crime operations in the provinces and cities.

Further, some big-ticket items, such as the purchase of ammunitions, are handled centrally in order to avail of economies of scale.

Plugging leaks

These resources are eventually distributed to field units, Ramos says. But with no clear guidelines on how much certain activities actually need, critics say funds tend to be disbursed at the whim of the generals.

And having an incumbent chief play favorites with his people is not even the main problem. The bigger problem in situations where authority over resources is too centralized, DILG’s Robredo says, is that such conditions also open opportunities for large-scale corruption.

Indeed, like their counterparts in the military, the police top brass have not been immune to controversy.

In late 2008, PNP comptroller Eliseo de la Paz and several other colleagues became the subject of investigations shortly after attending an Interpol activity in Moscow. De la Paz, then accompanied by his wife, got briefly detained and interrogated at the Moscow international airport because he failed to declare the 105,000 Euros or P6.9 million in cash that they had in their possession at the time.

The incident sparked a probe at the time on the way the PNP has been handling its resources. (Inaction in the so-called Euro generals scandal is cited as one of the basis for the charge of betrayal of public trust currently lodged against Ombudsman Merceditas Gutierrez.)

More recently, as Congress investigated corruption in the military in the wake of the controversial the plea bargain deal between the Office of the Ombudsman and former military comptroller Carlos Garcia, it was also suggested that the police be investigated as well. Among other things, the issue of an inflated payroll has been raised.

Rather than fish around for possible shenanigans, however, Robredo says he prefers to focus on instituting systemic reforms. “Serious problems are products of a bad system,” he told Newsbreak in an interview. What is needed, he said, is to “set controls and mechanisms to prevent leakages.”

The new policy with respect to the distribution of the MOOE funds is one of those.

To avoid wholesale corruption, Robredo explained, discretion at the top should be reduced and devolved to the field units.

When the new formula is in place, Robredo estimates that centrally managed funds will effectively be reduced by about P458 million. He says he also wants to introduce more transparency into the system.” The funds of the station should be posted on the website.”

Improving morale

The new distribution formula is far from perfect.

There are other considerations for resource distribution, Ramos pointed out, besides headcount. Among them is the geophysical location of the unit. The living standards and the crime situation in an area also affects cost of operations, he said. “The needs of a unit in Tipo-Tipo, Basilan, is different from the needs of one located in Makati City.”

Considering where the PNP was coming from, however, it is a step in the right direction, a budget department insider said. “In the past, station managers don’t know what they are entitled to, in terms of MOOE. The second step is to determine just how much it costs to run every type of station.”

The impression in the field, Robredo explained, is that there is inequity in terms of resource distribution between the Crame and the field units. “We want police to see that we are taking care of them,” Robredo said.

The new fund distribution formula, he said, is just one of the reforms they have undertaken towards this direction. There were others.

For instance, he said, “salary savings went to them.” Late in 2010, he explained, the police establishment was able to generate P396 million in savings.

The amount was taken from the unused portion of the PNP’s budget for personnel services. This was the first time in years that the police ever received full bonus, he said. “Dati walang bonus na ganyan.”

This was made possible, he explained, because the DBM has been releasing salaries based on actual body count, not the total plantilla position.

Robredo is hopeful that reforms will eventually translate into better law enforcement.

“Take gasoline for instance,” he said, “if you have more gasoline, then you can improve police visibility as patrol can be more frequent.” With additional funds, he said, police at the station level may even be able to acquire small equipment such as two-way radios.

This improved capability, in turn, would hopefully translate to improvements in police response to crime. – Newsbreak

(This final part of Newsbreak’s security sector reform series is made in partnership with the Friedrich Ebert Stiftung)

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.