SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Part 1 of 3

READ: Part 2: The politics of the coco levy scam: From Marcos to Noynoy Aquino

READ: Part 3: Return coco levy to farmers? Duterte’s promise and political will

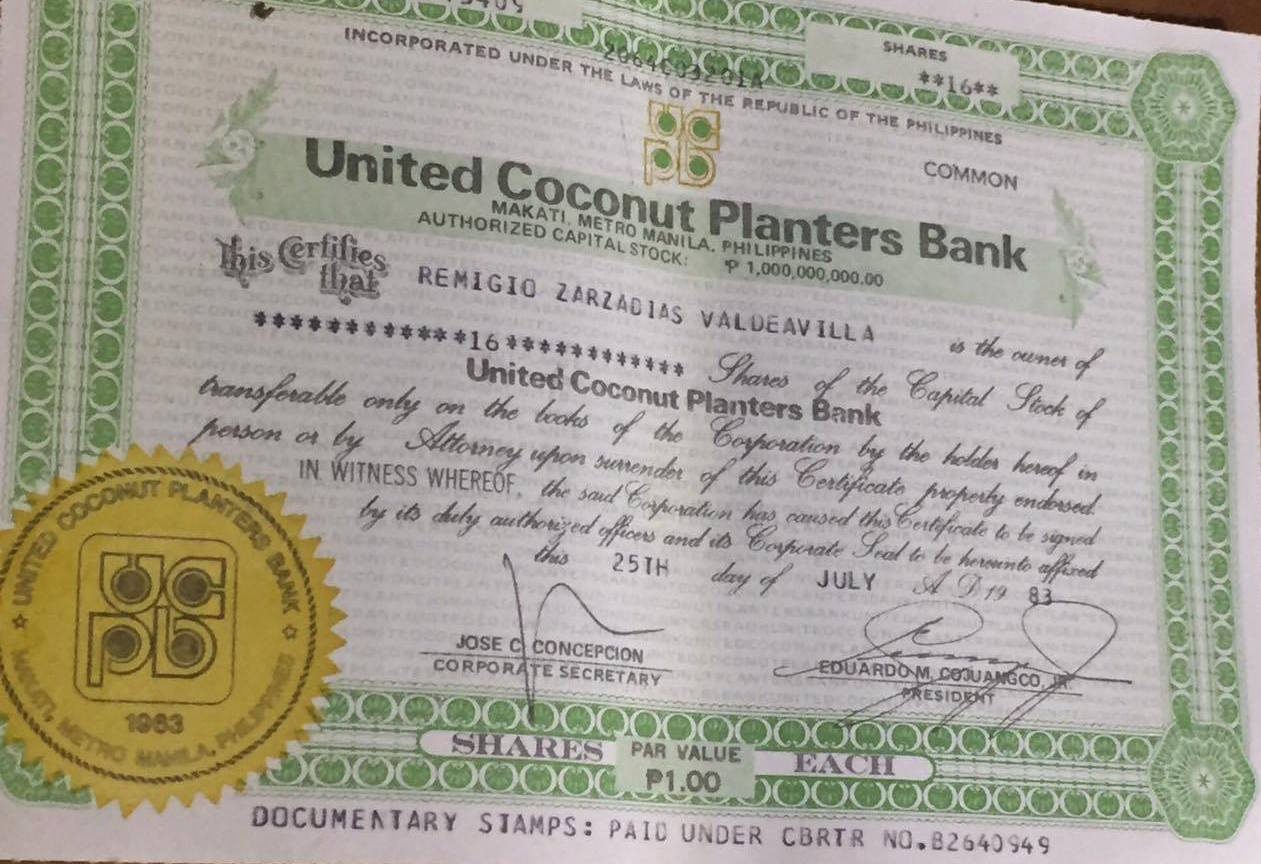

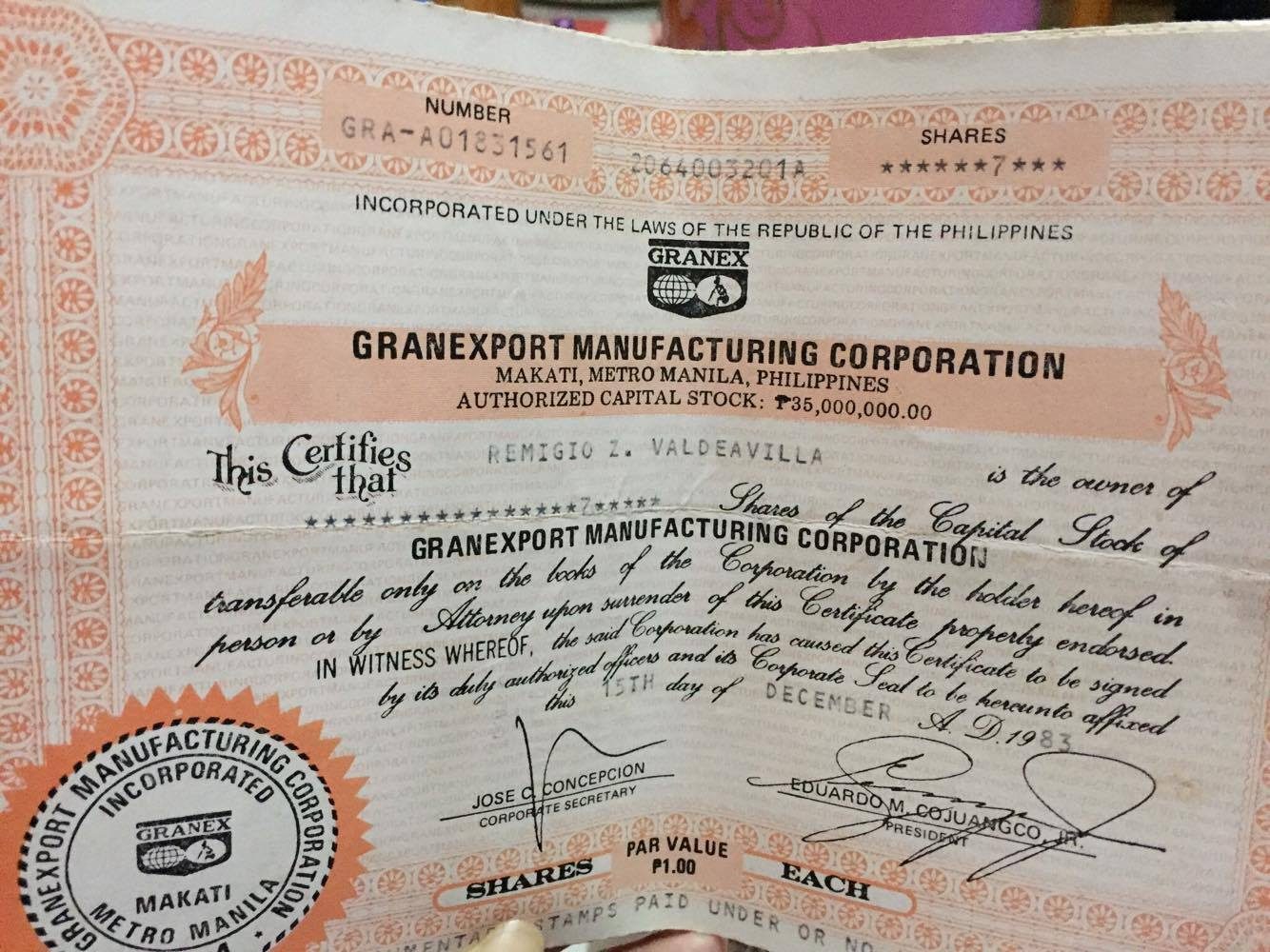

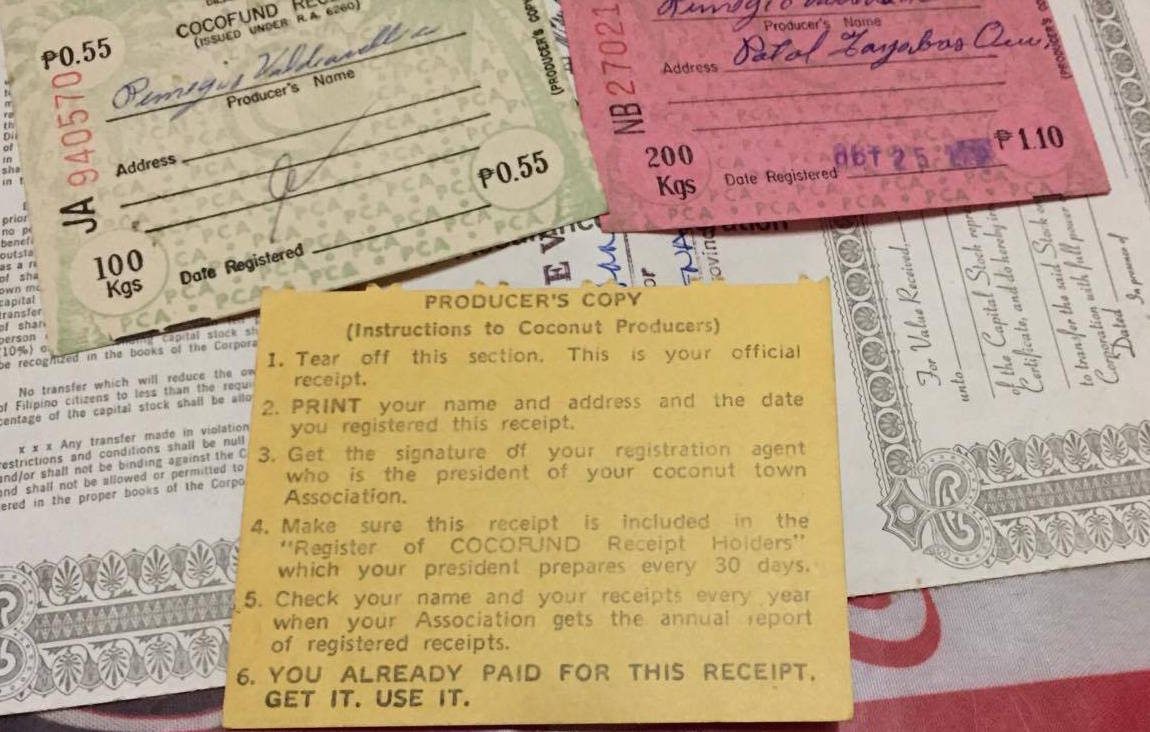

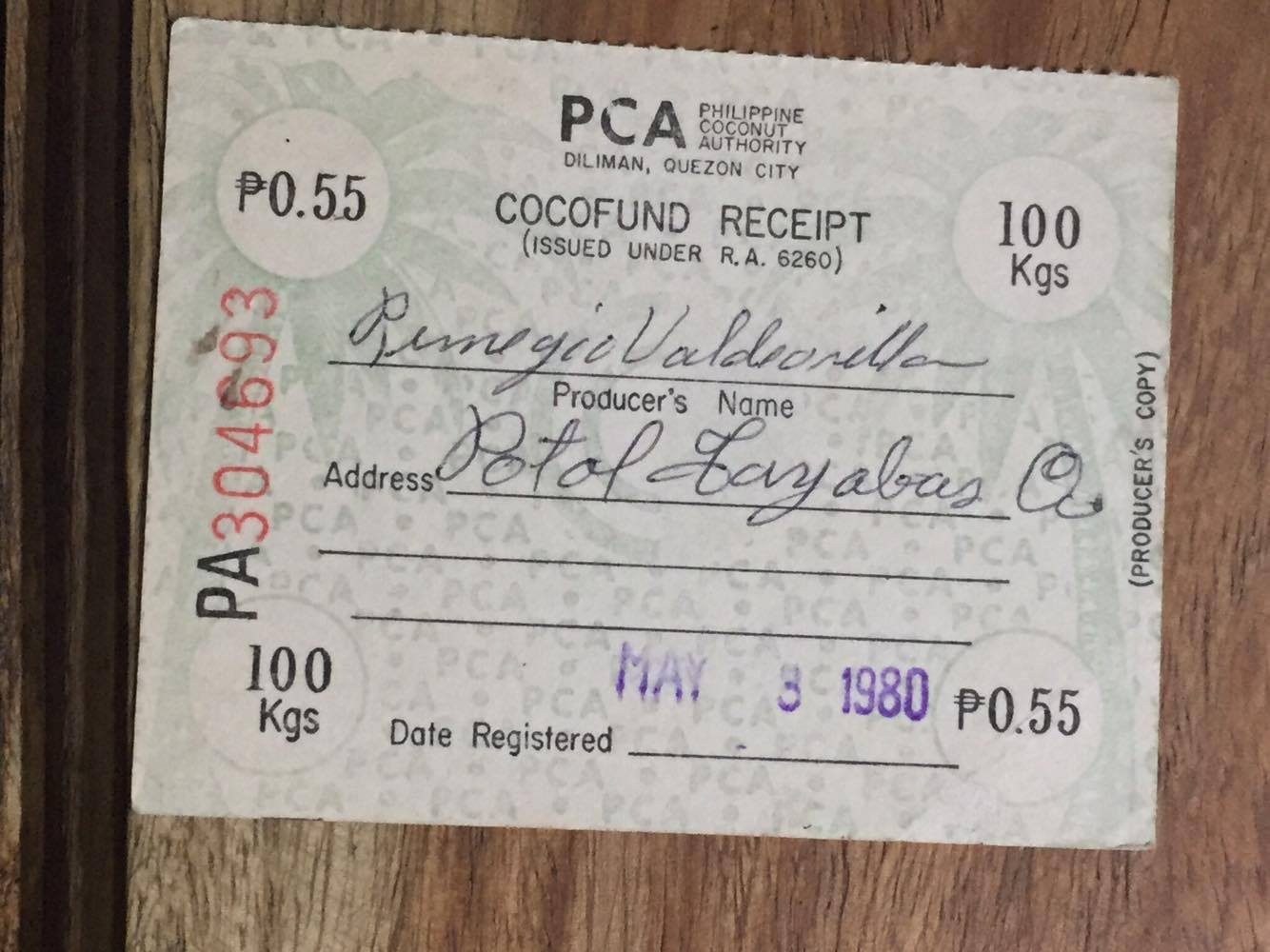

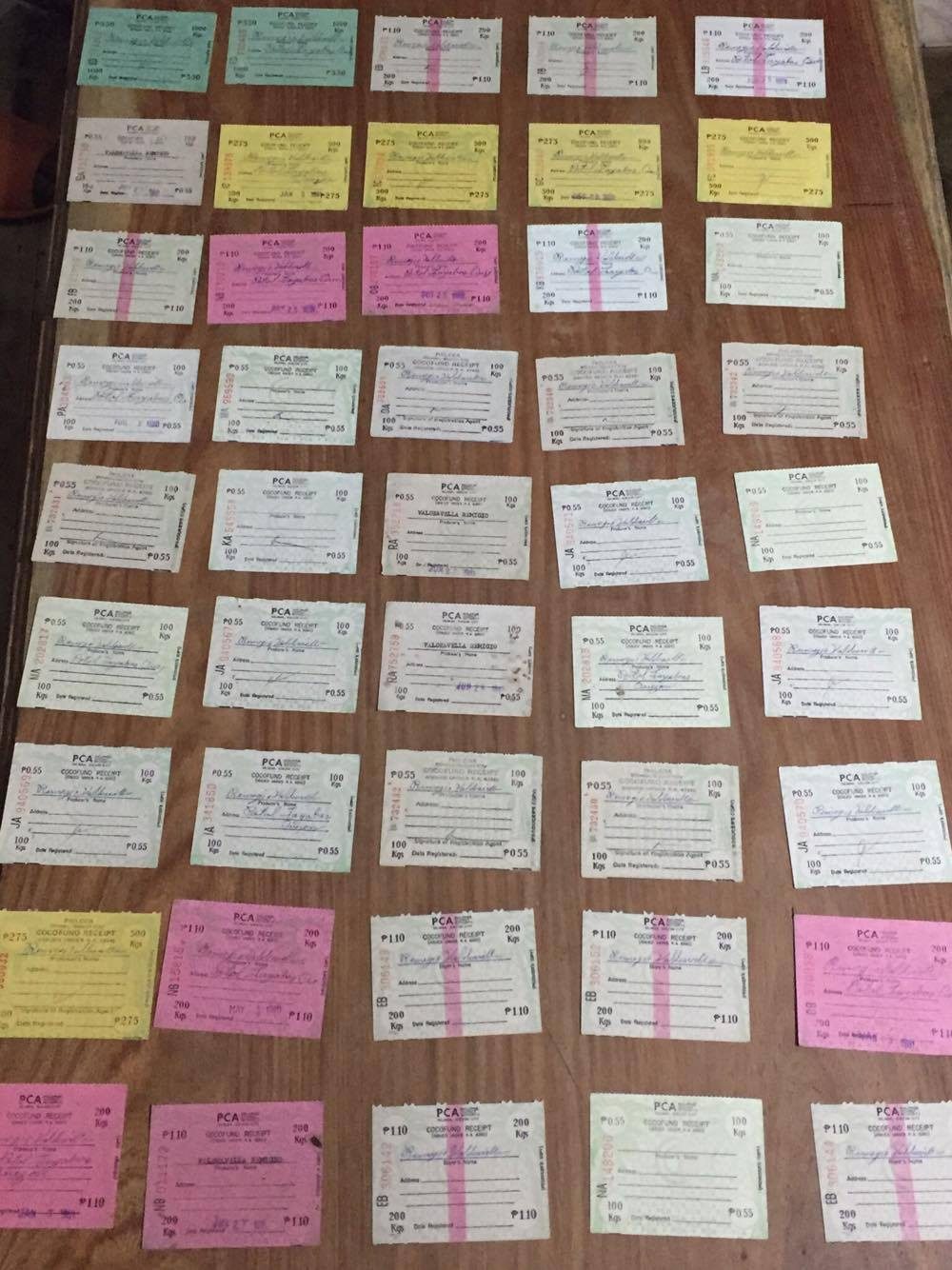

QUEZON, Philippines – It’s a long, uphill climb to Barangay Potol in Tayabas, Quezon, one of the coconut farming towns in the province. Just a few kilometers away from urban centers are makeshift bamboo bridges that have failed residents several times for the past decades. Left with no option, residents like Aling Rosing, Ka Sita, and Mang Ruben live with the risk and go on with their lives. The 3 are among the 3.5 million coconut farmers, earning an estimated P16,000 annually and belonging to the country’s poorest of the poor. They are victims of the coco levy fund scam from 1971 to 1983 under the Marcos administration, with collected taxes amounting to P9.7 billion. These farmers were taxed by the government, only for their payments to be used by former president Ferdinand Marcos and his alleged cronies, Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco Jr, Juan Ponce Enrile, and some others, to invest in and buy businesses for their own benefit. More than 45 years since the taxes were imposed on their coconut products, farmers have yet to receive the benefits promised them. They have had no option but to face reality and wait for the day when the funds – rightfully theirs – would be returned to them. On Wednesday, January 18, several coconut farmers held a protest anew in front of the Department of Agriculture in Quezon City to demand the release of funds, which the Supreme Court ruled to belong to the public in 2014. With stock certificates Aling Rosing Valdeavilla, 77 years old, and her departed husband Remigio have been coconut farmers for more than 5 decades. They relied mainly on coconut and rice farming to support their 6 children. Years may have passed, but for her, it seems just like yesterday when the government promised them “rewards” in exchange for taxes collected from their copra sales. Her husband died in 2013, and with him went the hope that they would one day reap the promised “rewards.” She has carefully kept the “stock certificates” or the certificates indicating their supposed ownership of stocks of certain companies where their money was invested – United Coconut Planters Bank, Cocolife insurance, Legaspi Oil Company, Granexport Manufacturing Corporation, and San Pablo Manufacturing Corporation, among others. Cojuangco was among the signatories in the documents.

Upon the collection by the PCA of the initial P100 million, they established the Coconut Investment Fund (CIF), a capital stock subscribed to by the government for, and in behalf of, the coconut farmers.

The taxes imposed grew as years went by, reaching P100 per 100 kilos. The collections, amounting to P9.7 billion, were used by Marcos and his cronies to set up or invest in businesses for their own benefit. This was also used to acquire two huge blocks of shares in the biggest food and beverage conglomerate in the country, San Miguel Corporation. (READ: The San Miguel-coco levy saga) Coconut Industry Reform Movement (COIR) director Joey Faustino said stock certificates of the companies were distributed to 1.4 million individual names of coconut farmers, like Aling Rosing, to “make it appear that coconut farmers owned them.” “While the farmers were issued 4 to 60 shares each, the cronies carried tens of millions of shares in their own individual names and their dummy companies. The farmers never even knew they were robbed of billions of pesos,” Faustino said. At present, the PCGG said there is a total of P93 billion in coco levy assets. But the real value of total assets is more than this, as some are still under litigation. Gold for the rich, crumbs for the poor Despite the billions of pesos they technically own, coconut farmers continue to be among the country’s poorest of the poor. A coconut farmer can be considered lucky if he or she has his or her own land to till. But for the majority, this is a far-fetched dream. The common rule is 60-40 – 60% of income goes to landowners while 40% goes to tenants. Prices of copra are dictated by the market. Sometimes copra prices could go as low as P6 per kilo and, on rare occasions, as high as P60 per kilo. At present, the price of copra is pegged at P35 to P40 a kilo. If a farmer gets to sell 100 kilos, he could get as much as P4,000 but P2,400 will go to his landowner and he will be left with P1,600. But before he could take this home, he has to pay coconut pickers if he is not strong enough to do so, fruit collectors, coconut husk removers, and haulers. These could amount to P200. The remaining amount – P1,400 – has to be shared by co-tenants, usually 3 to 4 persons, leaving each with little to no money left to raise a family. “On the average, karanasan namin noon, tanda ko pag nagsimula magcopra ang tatay kasama ang mga kasagpo ay ano e, halos breakeven or kung may matira kaunting kaunti lang. Sapat lang na konting bigas kasi habang nagko-copra, nangungutang na sa pinadadalhan ng copra,” Ka Sita said. (On the average, in our experience then, I remember when my father started making copra with his co-tenants. After he sold them it was just breakeven or if there was something left, it was just enough to buy rice. Because while you’re making copra, you already borrow money from the buyer.) “Mas mahirap mag-copra, lulutuin mo pa yun, lulukarin mo, sa tabi ng kalye ang sulitan, kaya kaunti na lang natitira. Kami’y tenants lang, ilan kami magkakapartida, 3 o 4, e di hati pa roon. Hindi sasapat,” Mang Ruben shared. (It’s more difficult to make copra because you have to cook it, you have to get the meat. The selling station is far, it’s beside the road, that’s why very little is left for us.) “Sisenta-kwarenta. 60-40 ang hatian. Maliit na lang napagkakasya namin kaya kami’y nag-aalagang baboy, saka kabayo at kalabaw,” Aling Rosing said. (The sharing scheme is 60% and 40%. We make do with the little that we get. We also raise pigs, we used to have many of them before, horses, and carabaos.) Of their total tax payments, Aling Rosing has received only a sum of P10,150 from coco levy companies. She received P150 when she claimed the equivalent of her shares – pegged at P1 per share – as shown in the stock certificates.

READ: Part 2: The politics of the coco levy scam: From Marcos to Noynoy Aquino

READ: Part 3: Return coco levy to farmers? Duterte’s promise and political will

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.