SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – “Taghai, bolan, songhot, adlo, abaca, sabun, ayam, ido, balay, boloto,” reads Filipino historian Ian Alfonso.

(Cup, star, moon, sun, cloth material, shirt, dog, house, small boat.)

These ancient Bisaya words leap from a digital copy of a 16th century French manuscript – one version of the account of a Venetian named Antonio Pigafetta, the first Westerner to document the Bisaya language.

Alfonso goes through this dictionary of sorts, rendered in flowery font by a scribe for the reading pleasure of European royals wanting to learn more about distant islands.

Alfonso uses laptop keys to turn the pages, as his boss, chairman of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), Rene Escalante, looks on.

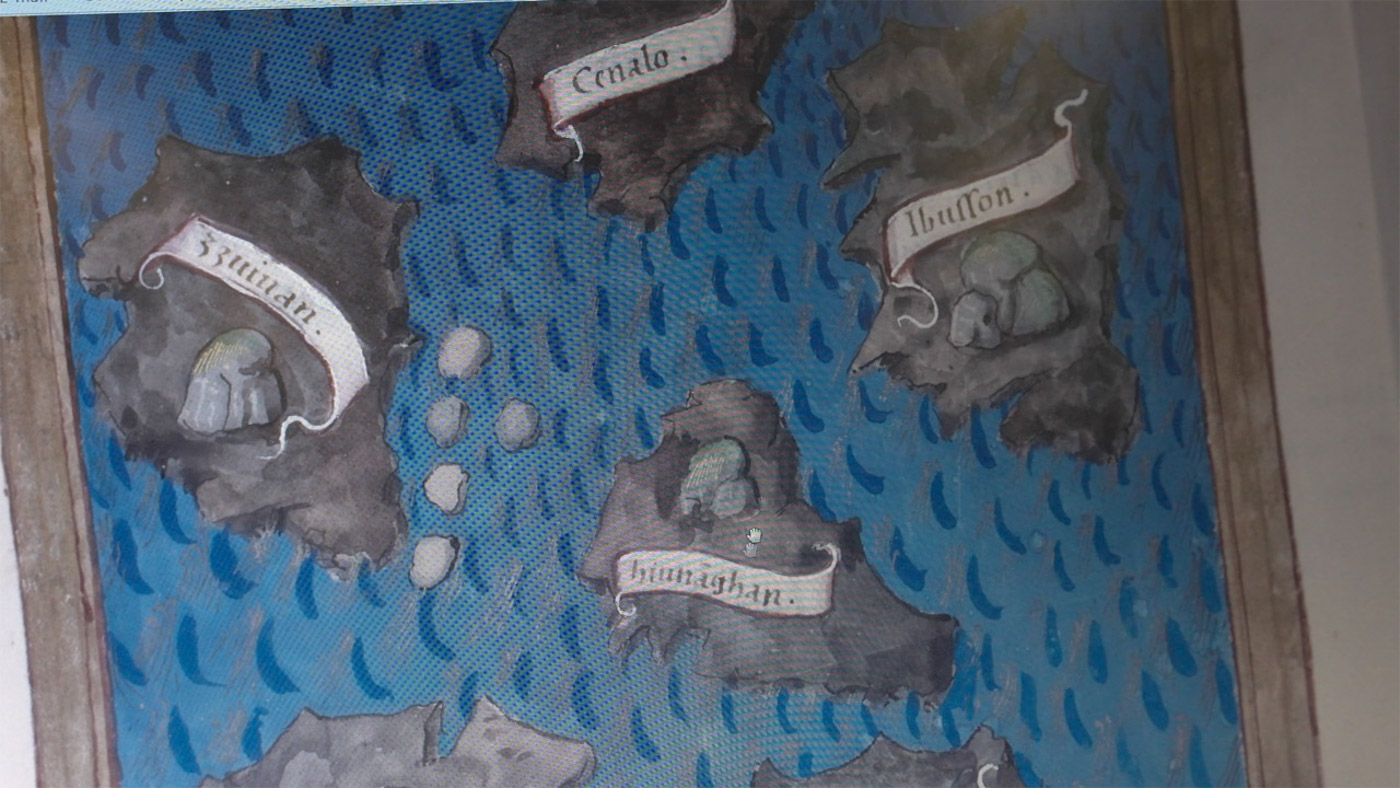

A few keyboard taps later, pages of words give way to pages of paintings. Grey islands pop from a blue backdrop of wave-flecked sea. White banners proclaim them to be depictions of “Mattan,” “Zubu,” “Bohol,” “Zuluan,” “Humunu,” and “Pulawan.”

They are known today as Mactan, Cebu, Bohol, Guiuan, Homonhon, and Palawan.

“We’re almost at the first encounter,” says Alfonso excitedly, as he uses his laptop to arrive at the page where Portugese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and his crew catch their first glimpse of the Philippine islands and are about to meet their first “natives” in Guiuan, Eastern Samar.

A year ago, Alfonso would have had to travel to the United States or Europe to view Pigafetta’s manuscript in high resolution, and likely be asked to pay a fee.

But he is viewing them in Manila, inside the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) library beside Rizal Park.

This access can now be enjoyed by any Filipino for the first time because the NHCP has finally brought home high-resolution digital copies of all 4 Pigafetta extant manuscripts.

Some of these manuscripts have long been accessible online, but not in high resolution, a limitation for historians who want to see crucial details or for the government who may want to use blown-up images of the documents.

TIDES OF TIME. A close-up of the Pigafetta manuscript kept in the Yale University library shows old names of Philippine islands. Photo by Adrian Portugal/Rappler

Antonio Pigafetta was a young Venetian, likely in his 20s when he arrived in the Philippines as part of Magellan’s crew on March 17, 1521.

The geographer and scribe of the group, he recorded not only names of places and the vocabulary of the natives, but their food, attire, customs, and traditions, too. He described historical events like the first Easter Day Mass celebrated in the Philippines and the battle of Mactan, where Magellan was killed by Lapulapu’s men.

Pigafetta’s eyewitness account is the “most detailed and only surviving account” of this critical event in Philippine history, says Escalante.

Pigafetta wrote all his observations in a journal, now lost. But based on this original journal, 4 manuscripts were produced – 3 in French and one in Italian. They were distributed to European royals interested in financing their own expeditions to the Spice Islands.

These 4 manuscripts have survived. The originals are in libraries in the United States, France, and Italy.

Their pages are a treasure trove of knowledge about the Philippines’ mysterious precolonial past – when chieftains ruled independent fiefdoms, animals and plants were sacred, and Western civilization was hazier than myth.

Collecting the manuscripts

Like Pigafetta himself, Escalante has had to reach out to different parts of the world to bring home the high-resolution digital copies of all 4 manuscripts.

While in New York City for negotiations on the return of the Balangiga Bells, he decided to take a drive to Yale University, only 3 hours away, where one French manuscript is kept.

After paying roughly P20,000 and promising to abide by conditions like not using the document for commercial purposes, Escalante secured a high-resolution digital file of Pigafetta’s account for the Philippine government.

He would later on write to two other institutes – the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris and Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan – which possess the remaining 3 chronicles.

The Ambrosiana manuscript, the longest of the 4, was the priciest, costing the government P100,000. The two manuscripts in Paris were obtained for only some P5,000 after the library gave NHCP an 80% discount.

In total, the government spent P125,000 for the manuscripts.

The government’s expense is the Filipinos’ gain. With all 4 digital copies now with the NHCP, any interested citizen can troop to the commission’s office in Rizal Park and request to view Pigafetta’s accounts, free of charge.

A request can be made with an email to nhcp.chair@gmail.com indicating the name of the requestor and the purpose of the request.

With this kind of access, anyone can be a historian.

“In history, there is still this passion for primary sources. If you really want to be a credible historian, you should not be [content] with translations and secondary accounts,” said Escalante.

Bringing home the Pigafetta manuscripts is one way to promote the study of history, especially that chapter in the Philippines’ shrouded in mystery.

As one explores further and further into the past, the number of materials about the time period diminishes. The only artifacts in our own backyard that have shed light on precolonial Philippines are jars, human remains, and epics preserved by oral history.

That’s why written accounts by foreigners who visited the Philippines in that epoch are valuable, and the Pigafetta manuscripts all the more so, for their level of detail and the historic events they describe.

For instance, Pigafetta narrates that the first Easter Day Mass was celebrated in the Philippines in a place called Limasawa. Despite a law in the 1960s declaring that this happened in Limasawa Island, Southern Leyte, there remain adherents to the theory that the site was Butuan, in a swampy area that had been called Mazaua.

Pigafetta also relates the planting of a cross in a mountain in Limasawa, and days later, in Cebu, the bequeathal of a statue of the baby Jesus to Juana, wife of Bisaya ruler Raja Humabon.

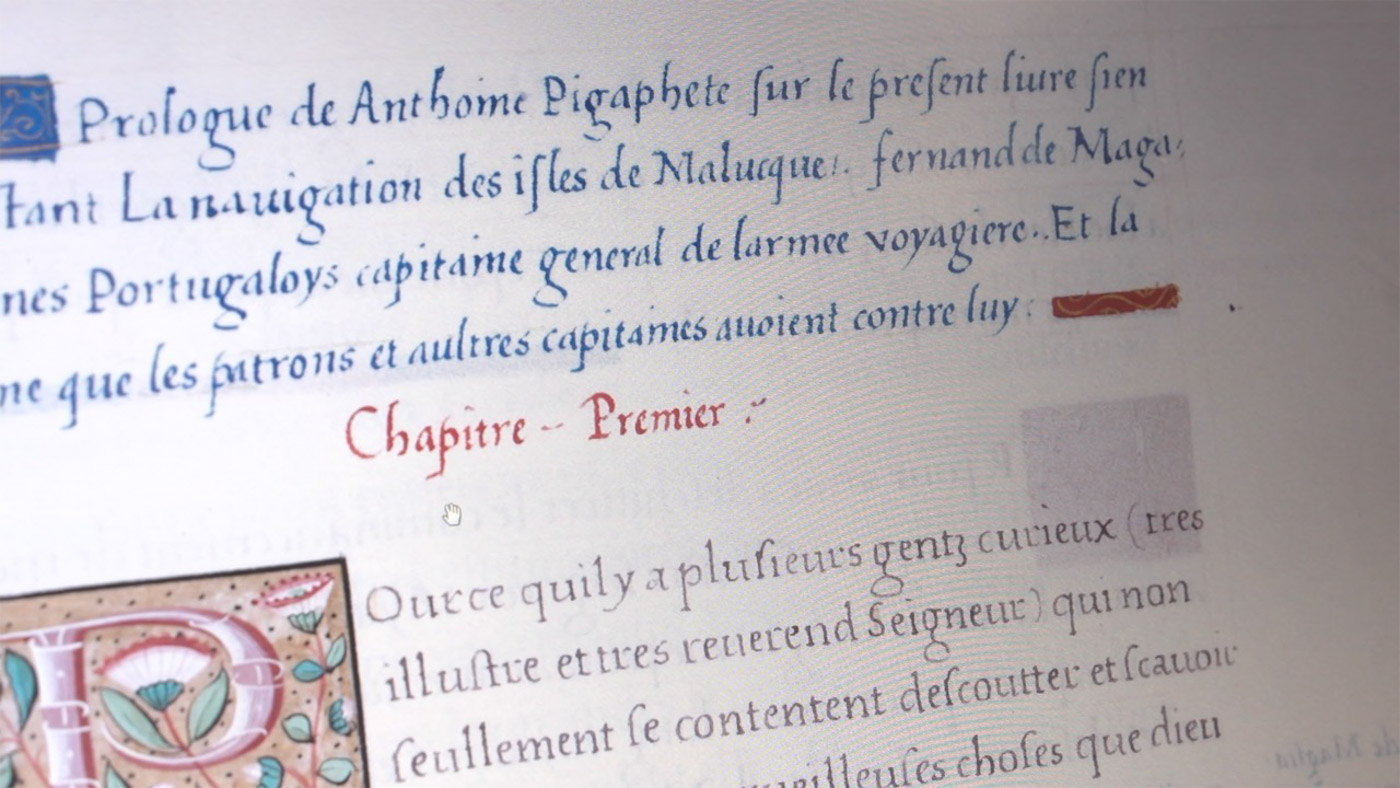

BEGINNING. The first chapter of one of the French versions of Pigafetta’s account begins with an introduction. Photo by Adrian Portugal/Rappler

The climax of Pigafetta’s account is Magellan’s death in the Battle of Mactan. Reading his chronicle would challenge what most Filipinos know about that historic event.

Pigafetta wrote that Magellan was killed, not necessarily by Mactan ruler Lapulapu himself, but by a swarm of his men. After a blow to his leg at the height of the battle, Magellan fell face down in the water where he was besieged by Lapulapu’s men.

“Immediately they rushed upon him with iron and bamboo spears and with their cutlasses, until they killed our mirror, our light, our comfort, and our true guide,” wrote Pigafetta.

To be consistent with this narration of events, the government has begun efforts to replace the current Lapulapu statue in Mactan with a “liberty shrine” that more accurately depicts the collective effort that led to Magellan’s death.

It is from Pigafetta’s account that we learn Magellan’s death may have been due to his own folly because he had refused the help of a rival Cebu chieftain, Zula, against Lapulapu.

BISAYA HERO. A statue of Lapulapu stands in Manila. Photo from Shutterstock

Magellan asked Zula and his men to stand back and watch the battle, confident that the Europeans outmatched Lapulapu’s army. The mistake cost him his life.

Apart from historical events, Pigafetta jotted down his observations about even the mundane details of the lives of early Filipinos.

He devotes paragraphs to describing Filipinos’ many uses of the coconut – a source of liquor (“uraca”), oil, vinegar, bread, and milk. He enthuses about how Butuan was full of gold “the size of walnuts and eggs” and how its king, Rajah Colambo, was the “finest looking man” they saw.

There are descriptions of the food served to them (roast pork, roast fish, ginger, bananas), attire, drinking ceremonies, burial rituals. Pigafetta speaks of the islanders’ habit of chewing a fruit called “areca” with betel leaves because of its “cooling effect.”

For Escalante, returning to Pigafetta’s manuscripts allows Filipinos to learn about a part of Philippine history “unadulterated” by colonialism. It would challenge the misconception of some that Filipinos, before colonization, were savages.

“We can tell them that we have already a respectable degree of ciivlization, we have forms of government, we have customs and traditions, we have appreciation of art, we are practicing also basic agriculture. We have developed the technology of boat-making and then land-navigating and seas,” said Escalante.

But the value of the manuscripts lies not only in Pigafetta’s words, but also in their other visual elements. Not your modern-day drab, typed-up report, the chronicles are painstakingly handwritten and come with colorful paintings.

Scholars of calligraphy, cartography, drawing techniques, and early forms of languages would also have much to mine from the pages, especially in their high-resolution renderings.

Hike for history

One hot April day, Francis “Chas” Navarro found himself huffing and puffing up a hill in Limasawa, Southern Leyte with fellow historians.

Navarro, a history professor with Ateneo de Manila University was with church historians Father Tony de Castro, Victor Torres, and Brother Madz Tumbali; Rolando Borrinaga of University of the Philippines Tacloban, and Carlos Madrid, former head of Instituto Cervantes, an organization that teaches Spanish language and culture.

Their young guides said it would take only 15 minutes until the peak, but they didn’t consider how the steep assault would force Navarro and his companions to stop for rests and gulps of water.

They almost gave up.

Their hike up Limasawa was not for an adrenaline rush but to settle a historical debate – if the first Easter Day Mass was held in Limasawa, Southern Leyte or in Butuan.

In Pigafetta’s account, Magellan and his crew scaled a hill in the place where they would later on hold the Mass to see the entire island and its surroundings. This is apart from their other hike to plant a cross after celebrating the Easter Day Mass for the newly-baptized islanders.

Was it this hill the explorers climbed, thus proving Limasawa – and not Mazaua in Butuan – was the site of the Mass?

Navarro and his companions, sweaty and out of breath, found the answer at the peak as they looked out into the seascape.

“It was at that particular point that when they were up there, they saw 3 peaks. That would be the peaks of the mountains of Samar, Leyte, and another province, and it was verified that it could be seen at the peak of Limasawa,” said Navarro.

Madrid would later on climb a hill near the supposed location of Mazaua, the place in Butuan which some believe to be where the first Easter Day Mass was really held.

But Madrid did not see 3 peaks, which led him to conclude it was not the right place.

Navarro is part of a group of historians tapped by the NHCP to settle disputes on the March 31, 1521 Easter Sunday Mass celebration using the Pigafetta manuscripts and other primary sources.

Because of his expertise in the transcription of historical documents, Navarro was specifically tasked with the transcription and translation of the portion of the Pigafetta manuscripts that deal with the Philippine leg of the Magellan-Elcano expedition.

Navarro, who specializes in Spanish documents, asked the University of the Philippines’ Jillian Melchor and fellow Ateneo academic Robert Yu to translate the Italian and French manuscripts, respectively.

He himself focused on the accounts of Gines de Mafra and Francisco Albo, the other crew members who kept a diary or logbook of the expedition, among other relevant documents.

The Philippine portion comprises only 25% of Pigafetta’s account of the entire Magellan-Elcano expedition but transcribing and translating this is painstaking work. Transcribing is turning the characters of historical writings into Roman letters. Translation is when these writings are made understandable in another language, like English.

Months of transcriptions and translations, trips to different parts of the country, and dialogues with various historians championioning their own theories have borne fruit.

An effort that began in January will soon culminate in a final report the panel of historians is now finishing. Escalante said the findings would be contained in a two-volume book to be released in 2021 in time for the commemoration of the 500th-year anniversary of Magellan’s arrival in the Philippines.

It was the 2019 to 2022 quincentennial celebration of the Magellan-Elcano expedition or the First Circumnavigation of the World that catalyzed NHCP’s efforts to bring home the Pigafetta manuscripts.

In past years, the government had been more focused on commemorating events that took place during the colonial era, like the birth anniversaries of national figures like Jose Rizal, Andres Bonifacio, and Emilio Aguinaldo.

The quincentennial of Magellan’s journey gave NHCP the perfect opportunity to collect materials about that little-known time in the country’s past when ancient Filipinos answered to no foreign master.

The Pigafetta manuscripts are just the beginning of a long journey. The NHCP is looking for more sources of primary accounts of ancient Philippines from other countries, including its Asian neighbors.

They’ve reached out to Japanese, Chinese, Malaysian, Indonesian, Turkish, and Indian officials. NHCP historians have flown twice to Malaysia to follow up on some sources.

They’ve secured digital files of the richly-illustrated, 300-page Boxer Codex for a mere P5,000.

Some P10 million in public funds have been earmarked for the retrieval of such historical materials, said Escalante.

These documents would again have to be transcribed, translated, analyzed, and discussed extensively.

It’s work reserved for both the Philippines’ experienced and budding historians, who together, can weave an ancient world from centuries-old ink. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.