SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

AT A GLANCE

- A military risk analysis of its co-location deal with Dito Telecommunity appears to have been done only after the agreement was signed on September 11, 2019.

- Electronic and radio frequency eavesdropping, interception, and jamming, says the report, are among “highly likely” risks.

- Existing cell site deals with Globe and Smart present the same risks. However, Dito Telecommunity is partially owned by a Chinese state-run company, which is required by their laws to provide intelligence.

- Despite the threats, the military says the risks are “low” due to “existing control measures.” Yet “additional controls” are recommended.

MANILA, Philippines – It wouldn’t really say so in public, but the military itself recognizes the high likelihood of spying threats and the resulting damage posed by its deal allowing the China-backed 3rd telco to build cell sites in its camps and bases all over the Philippines.

In a risk analysis of its co-location agreement with Dito Telecommunity (formerly Mislatel), a copy of which was obtained by Rappler, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) identified several security threats to its communication systems “in relation to the telco agreements.”

This means even the cell sites of Globe and Smart, hosted in AFP properties since 1998, present the same risks. However, Dito’s direct link to the Chinese government means the 3rd telco poses a more imminent security threat.

China is after ownership and control of the West Philippine Sea, has the Philippine government tied up in loans worth billions of pesos, and is expanding its political and economic interests in the Philippines. It is fast dominating the Asia Pacific region as an economic and military power.

The Chinese government owns China Telecom (Chinatel), which owns 40% of Dito Telecommunity. Chinese law mandates companies it owns – like Chinatel – to provide intelligence to the government.

Although Chinatel is a minority stakeholder in Dito, a consortium that also includes Davao-based businessman Dennis Uy’s Udenna Corporation and Chelsea Logistics, the Chinese company will be building the telco’s communication infrastructure all over the Philippines, and will be involved in its daily operations.

That means Chinatel would have at least some control over Dito’s equipment that would be placed inside military properties, and the personnel who would set them up.

Barrage of criticism

After the AFP and Dito signed the co-location agreement on September 11, 2019, the military immediately faced a barrage of criticism from several lawmakers and security experts, who found the trade-off too obvious.

Why should the military host the equipment of a company with links to a country that covets Philippine properties?

Senior generals gave assurances they have put in place measures to protect against information security breaches, and that Dito’s equipment would be separate from the AFP’s own communication lines, not necessarily in camps.

Besides, public clamor for a 3rd telco to break the duopoly of Globe and Smart justifies military support, the AFP said, especially since the first two telcos have long had a similar co-location arrangement. Another player can only further boost the military’s own data connection.

In short, the military said, the benefits it would get from the deal with Dito far outweigh the anticipated risks.

Analysis after the fact

The AFP’s internal study describes the co-location deal’s information security risks in considerable detail – far more than anything that defense and military officials have acknowledged publicly.

The 7-page document was prepared by the AFP Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Communication, Electronics and Information Systems (J6). Its first page contains an introduction that refers to the signing of the Dito contract on September 11, 2019 in the past tense, which means the study was done after, and not before, the military agreed to the telco’s co-location proposal.

Rappler earlier obtained and studied copies of the military’s co-location contracts with all 3 telcos for any hints of security risks, and found that they offer no real assurance of protection against spying or data theft.

The risk analysis of the deal with Dito now clearly identifies and confirms several such risks and gives a broader picture of what the co-location agreements between the military and the telcos really entail.

AFP J6 chief Major General Adrian Sanchez Jr and then-AFP chief of staff general Benjamin Madrigal Jr signed the contract to represent the military. Dito’s chief administrative officer Adel Tamano signed off for the telco.

The deal still needs the final approval of Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana, who agreed to defer signing the contract until the Senate finishes studying the deal’s security implications. The Senate has yet to give its final recommendation.

Because Dito still lacks the final go-ahead to build its cell sites, the AFP J6 based its risk analysis on the existing infrastructure of Globe and Smart inside military camps and bases. The premise is that Dito’s infrastructure will be largely similar to that of the other telcos. (READ: Experts warn of spying risk in AFP deal with China-backed telco)

What are the vulnerabilities?

The AFP J6 identified two of the military’s existing wireless communication systems that “offer some vulnerability to interception” heightened by the presence of telco equipment:

- AFP Fixed Communication System (AFP-FCS) – A fixed-station microwave network that links together military camps and bases nationwide. It relies on line-of-sight signals transmitted across free space. The military calls it its “main communication backbone.”

- AFP High-Frequency Radio Voice and Data Communication System (AFP-HF) – Provides communication linkages within and between military forces over considerable distances, usually deployed in tactical applications. It also serves as an alternate communication system for operational headquarters, and as back-up for the General Headquarters, the AFP Command Center, and Major Services Operation Centers.

Each system has its own vulnerabilities, but both the AFP-FCS and the AFP-HF are susceptible to eavesdropping and interception, according to the risk analysis.

Eavesdropping is when a third party listens in on communication through a device embedded in the system, or in the case of radio communication, by tuning into the frequency or channel of the transmission.

Interception is when a third party cuts in on transmitted communication through a device placed in the path of the transmission airwaves.

The AFP-HF is also vulnerable to jamming – the blocking or interference of existing radio or wireless communication systems, the analysis said. Microwave signals can also be jammed, which means the AFP-FCS could be susceptible to it, too, but the risk analysis does not mention this.

The systems’ vulnerabilities exist regardless of their proximity to telco equipment.

What the AFP implied in its risk analysis was that the telcos could exploit these vulnerabilities, thus turning them into imminent threats.

Interception: Man in the middle

The AFP-FCS is a terrestrial, or land-based, voice and data microwave system, which the military calls its “main communication backbone.”

Its objective is to “interconnect the General Headquarters and Area Commands, Major Services, down to Infantry Division level with high grade, reliable voice and data communication infrastructure for the efficient and effective command and control and administration of the AFP,” according to the risk analysis.

The General Headquarters cover the military top brass stationed at Camp Aguinaldo in Quezon City. The Area Commands include the Northern Luzon Command, Southern Luzon Command, the Western Command in Palawan, the Central Command in the Visayas, the Eastern Mindanao Command, and the Western Mindanao Command.

The Major Services cover the Philippine Army headquartered at Fort Bonifacio in Taguig City, the Philippine Navy headquartered at Naval Station Jose Andrada in Manila, and the Philippine Air Force headquartered at Villamor Air Base in Pasay City. The Army has 11 Infantry Divisions all over the country.

The AFP-FCS uses the microwave frequency to transmit voice and data among these units. Microwave transmissions interconnect on a line-of-sight basis, meaning any physical obstruction in the airspace between transceivers, such as mountains or skyscrapers, can limit or cut their connection.

Similarly, it is quite easy to cut into transmissions from the AFP-FCS. “Microwave links, like most wireless communication systems, are susceptible to electronic eavesdropping and interception,” the AFP J6 said in its analysis.

“Equipment to intercept [these] signals is readily and cheaply available,” according to the analysis, citing the “man-in-the-middle” attack as “the most common method of exploiting the vulnerability of an unsecured microwave link.”

All anyone needs to do to intercept a message sent through a microwave link is to put interception equipment in the line of sight between two communication towers or cell sites, and if the link is unsecured, the “man in the middle” is able to spy.

Jamming: ‘Particularly vulnerable’

The AFP-HF, meanwhile, is described as an “alternate” or “back-up” communication system among the AFP’s different units over longer distances because its wavelength enables transmission beyond line-of-sight.

It is “usually deployed in tactical applications.” This refers to field missions and combat scenarios, because high frequency (HF) radio waves can be beamed towards the sky, and the ionosphere bounces them back to Earth, enabling the signal to cover vast distances regardless of terrain. This “skywave” method of communication can traverse mountains and follow the curve of the Earth to reach beyond the horizon, allowing even for intercontinental transmission.

“Like most radio systems, HF is particularly vulnerable to interception and electronic/signal jamming considering the nature of radio waves to use free space as the medium of transmission,” the AFP J6 said in its analysis.

Signal jamming equipment can obstruct the reception of HF communication, and it has historically been used in battles to foil enemy plans.

Communication signals are also usually jammed to avert security threats during high-risk scenarios, such as the yearly Black Nazarene procession in Manila, or during the arrival of the President at a conflict zone.

Eavesdropping: listening from the inside

What might really interest China in Dito’s co-location deal with the AFP is physical access to its camps and bases, because it could present an opportunity to eavesdrop on the military.

Interception and jamming can be done from outside camp; eavesdropping happens right at the source.

The risk analysis states that an “electronic or data gathering device may be installed in or within the AFP communications facility for eavesdropping purposes.”

This means that in the course of Dito’s installation of its transceivers on the military’s communication towers, the telco’s personnel could also put bugs or other surveillance devices in areas they would be able to access. The transceivers could have spying devices embedded in them.

In the case of the AFP-HF, eavesdropping can be done by “capturing and listening to the radio frequency channel of the [military’s] HF radios,” the document said.

4 ‘threat events’

Electronic eavesdropping, interception, and jamming of communication signals have a long history of being used in espionage and warfare. A quick Google search of “signals intelligence” or “SIGINT” would turn up professional sources attesting to the fact.

The risk analysis downplayed the concern that a telco’s presence, particularly Dito with its Chinese links, increases the likelihood of these threats happening. In the end, the AFP J6 concluded that “existing pro-active control measures” mitigate the “low” risks.

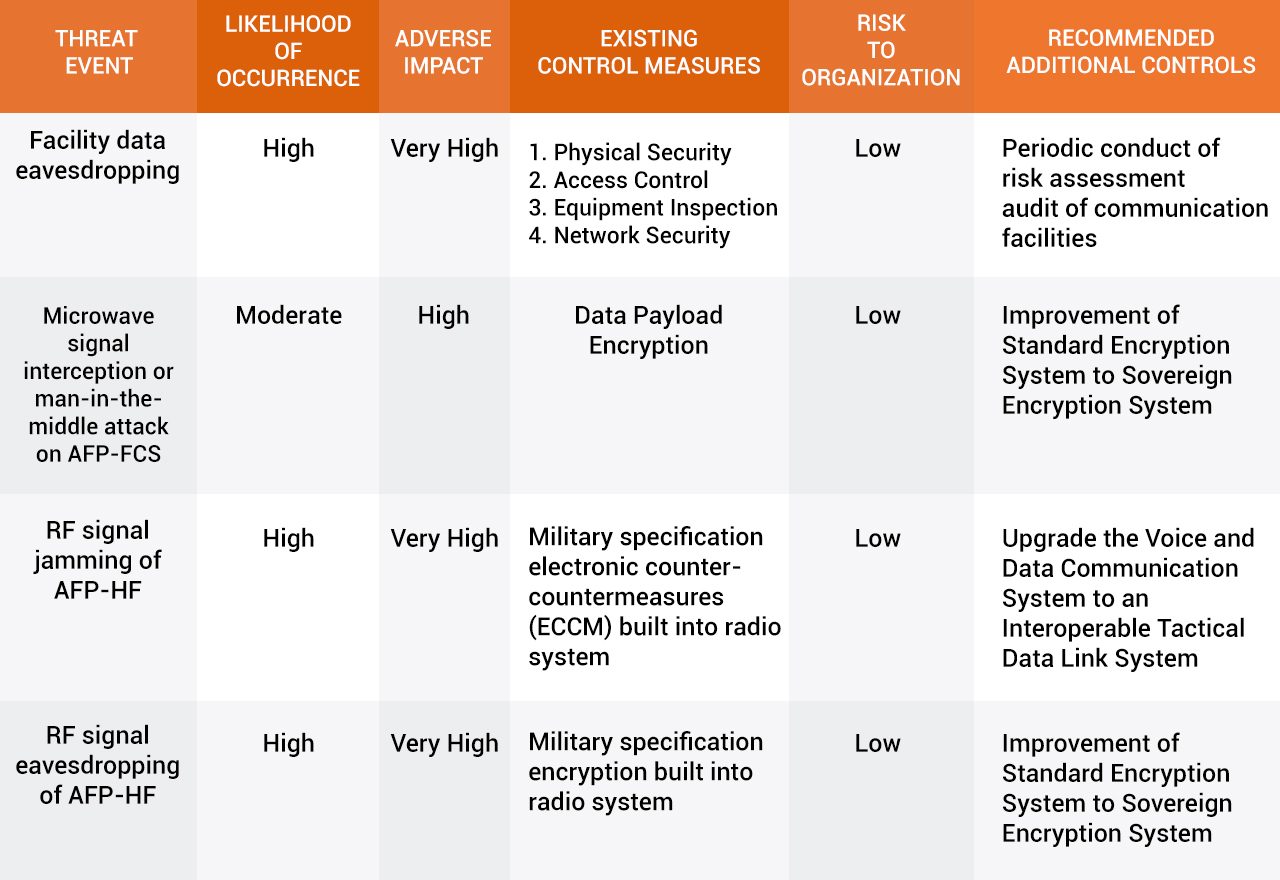

Using a method developed in 2012 by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) of the US Department of Commerce – the Guide for Conducting Risk Assessments, NIST Special Publication 800-30 – the AFP J6 enumerated and briefly defined 4 specific “threat events”:

- Electronic eavesdropping at the AFP communications facility – “Electronic or data gathering device may be installed in or within the AFP communications facility for eavesdropping purposes.”

- Microwave signal interception in between sites (man-in-the-middle attack) – “Interception equipment may be installed between the microwave links,” which are cell sites or communication towers. This involves the AFP-FCS.

- Signal jamming of the AFP-HF voice and data system – “Deliberate jamming, blocking, or interference with existing radio or wireless communications systems.”

- Radio Frequency (RF) signal eavesdropping on the AFP-HF – “Capturing and listening to the RF channel of the [AFP-HF] radios.”

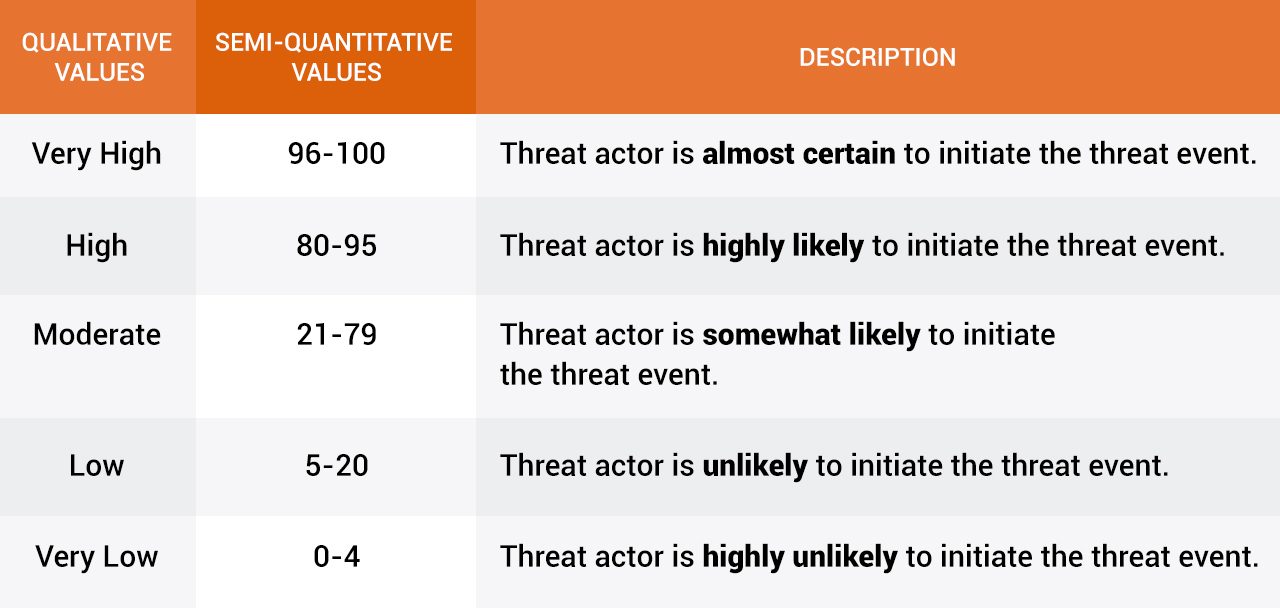

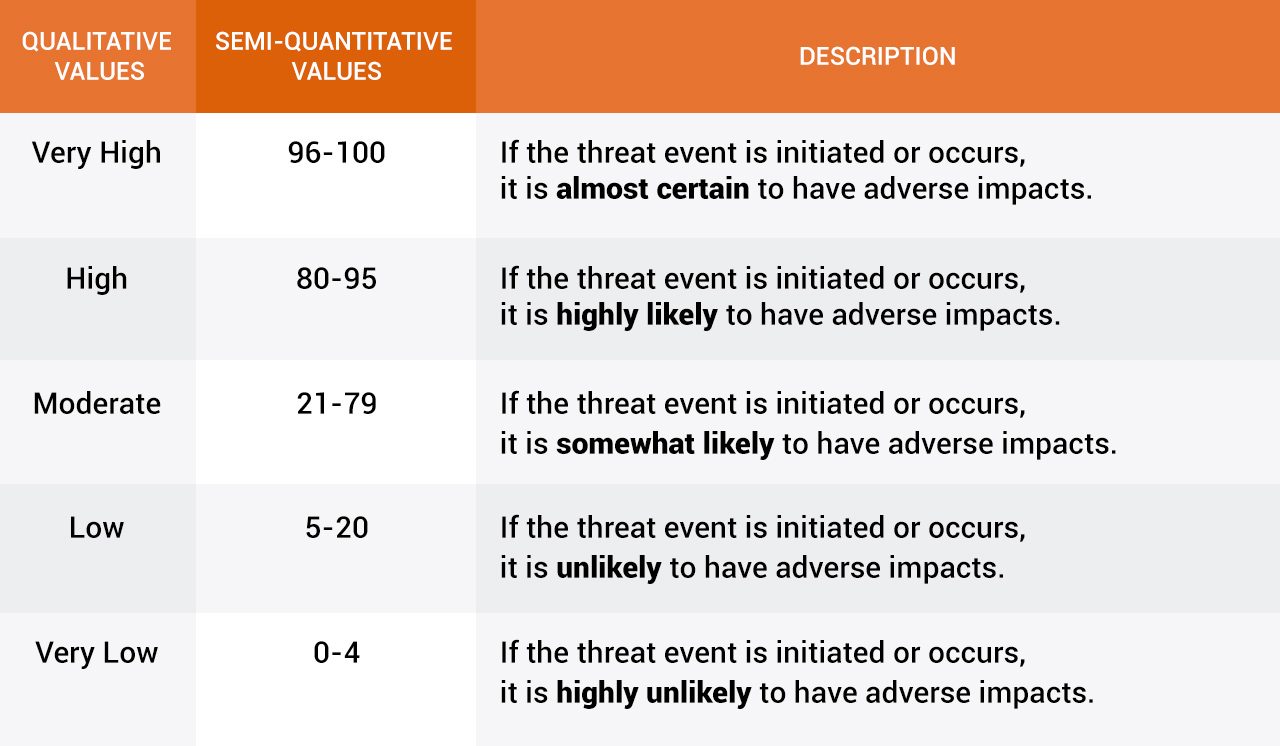

The AFP J6 “determined the likelihood of the threat event being initiated by the threat actor” – or how likely Chinatel would use Dito’s co-location deal to spy on the AFP – using the following scale:

They then used a similar scale to determine “the likelihood of the threat event resulting in adverse impact” on the organization:

With these qualifiers, the AFP J6 then analyzed the level of risk by leaning on the “effectiveness of the existing control measures that were adopted by the organization to mitigate” it.

All things considered, the AFP J6 said that all the risks from the threat events are low:

Note how the 6th column indicates “recommended additional controls,” which means the military’s “existing control measures” do not exhaust all possible ways of averting the spying risks from the co-location deals not just with Dito, but with Globe and Smart, too.

The risk analysis does not tackle microwave signal jamming, which could be a vulnerability of the AFP-FCS.

What are the ‘existing control measures?’

The AFP never categorically denied that the co-location deal could be used for spying.

It fended off questions and criticism by pointing out that it has “existing control measures” to prevent information security breaches and minimize their impact if they ever happen.

“Physical Security” and “Access Control.” This means the AFP would strictly limit and control which telco personnel would gain access to its communications facilities whether to install or maintain the cell sites. Only Filipino engineers and technicians are allowed to access the cell sites, “which are some of the most tightly guarded military installations,” the AFP J6 said.

Any foreigner seeking the same access needs to secure clearance from the AFP’s intelligence unit.

“Equipment Inspection” of every device the telcos would bring in. It would then depend on how thoroughly the AFP inspects the telco’s equipment, and how keen military personnel are in identifying questionable items if a telco tries to sneak in any.

“Network Security.” This involves physically separating the telco’s equipment from the military’s, and then monitoring data and signal traffic for breaches – hacking or eavesdropping. The AFP J6 said that although military and telco equipment share the same towers in military properties, they are segregated from one another.

The AFP said it runs a Network Monitoring System to “monitor and manage” signal traffic among its communication networks. It’s supposed to detect and block attempts to hack into the system.

“Data Payload Encryption.” This means messages sent over its microwave links are coded, and anyone who intercepts them would only get a garbled, unintelligible transmission.

As for the AFP-HF that uses high frequency radio waves, the AFP said it uses Harris radio sets, a US brand with built-in military standard protection. The radio sets come with an electronic counter-countermeasures (ECCM) suite that “filters radio traffic to provide reliable, secure HF communications in the presence of jamming.”

The AFP’s radio inventory from Harris also comes with the Citadel Cryptographic Engine, which encrypts radio transmissions, and should guard against electronic eavesdropping.

How effective are these control measures? This would be the big question. Whether the military’s conclusion of its risk analysis is accurate depends on the effectiveness of the control measures they claim to have.

Rappler showed the document to 3 independent experts on national defense, telecommunications, and information security, to get their opinion on the AFP’s assessment.

Their findings raised more questions, including whether the AFP has a good grasp of just what it is getting itself into by letting a China-backed telco into their midst. – Rappler.com

READ: Part 2 | Will PH military be China’s unwitting accessory to data breach?

TOP PHOTO: Is the Philippine military being used by China in a plan to cull data from Filipinos through a co-location deal with Dito Telecommunity? Photo of soldiers by Jire Carreon/Rappler. Photo of communication tower from Shutterstock. Collage designed by Alyssa Arizabal/Rappler.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.