SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Life seemed normal, until it wasn’t. Headlines blasted a new coronavirus had been spreading in places across the world and after weeks of sticking to daily routines, the virus covered over 190 countries and territories.

In cities where millions moved through daily, life ground to a halt as people receded into spaces barricaded by checkpoints. Streets and buildings, usually busy with exchange, were left empty and hollow.

Hospitals and health care centers saw the exact opposite where spaces were filled to the brim, patients coming in faster than others could leave. Scenes of cramped hallways and stadiums turned into makeshift hospitals flooded screens for days too many to count.

The cases climbed, along with death tolls, afflicting young and old alike.

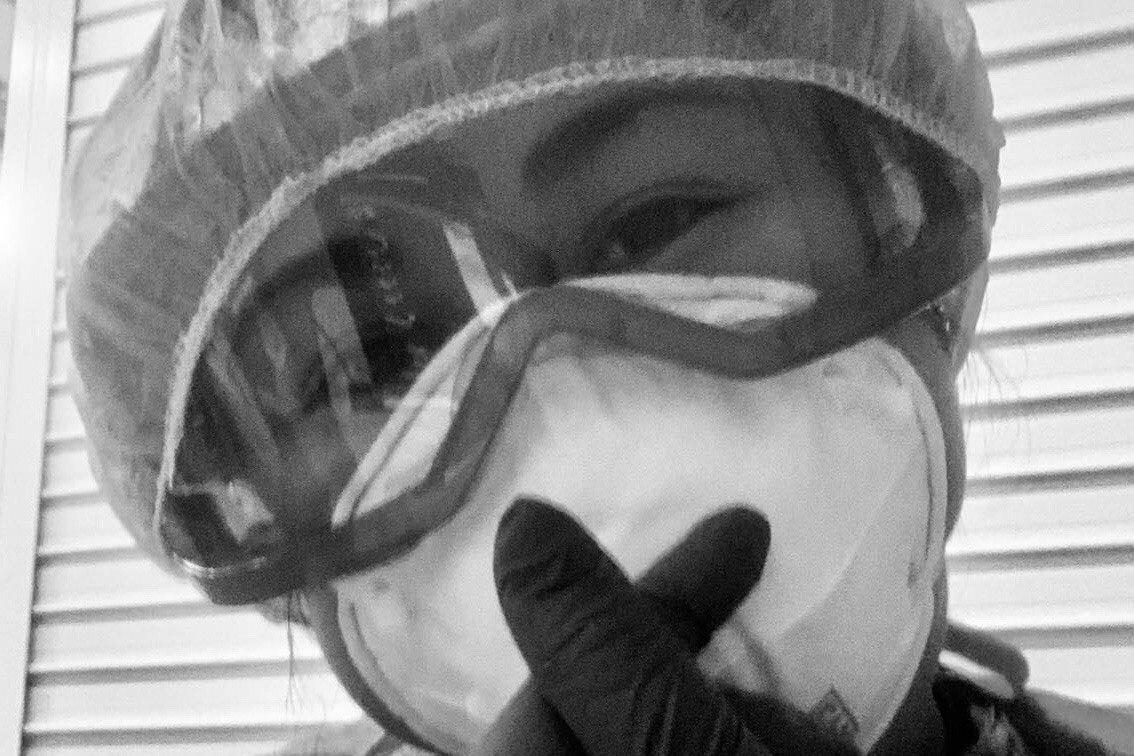

In many of these spaces, faces of Filipino health workers hidden behind a series of masks tended to the sick. Government data shows about 92,700 Filipino nurses migrated from the Philippines to work in other countries from 2012 to 2018. Their numbers add to the hundreds of thousands already overseas for over a decade.

In epicenters and high-risk spaces, Filipino far from home are thrust to serve on the front lines of the pandemic, scared and anxious, but bound by duty to care for those most vulnerable.

Bergamo, Italy

It was mid-March when the sick started swarming the Policlinico San Marco in Bergamo, Italy. Infected by the coronavirus, many of the ill could not talk so much as breathe, slowly losing life in waiting.

The hospital had the capacity for only 800 patients, while they came by hundreds by the day.

The intensive care unit for COVID-19 patients originally had a capacity for 8, with each nurse ideally watching, at most, two patients at a time on a normal day.

But normal has long been gone. Since the outbreak started, they have been handling 20 to 30 people. Staffers had to place patients in the hallways, resting them on wheelchairs or laying them down on stretchers over cold, tiled floors.

One of the nurses in the Policlinico’s intensive care unit (ICU) was Divina Guerrero, a bespectacled 53-year-old Filipina and mother of two, who, like her colleagues, never saw the virus coming.

“I could not explain how it happened but it’s like the world of Italy crumbled,” Divina said.

With over 214,000 confirmed cases, Italy is the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak in Europe. Its hub is the province of Lombardy, where over 79,000 patients are found. Ground zero of Lombardy is Bergamo, where there are over 11,000 cases.

The story of how the coronavirus exploded in their region is a familiar tale: The first cases emerged in a single area – in their case, the town of Codogno of over 15,000 people. The government tried to implement a lockdown, but it was too little, too late. Soon, what looked like a small sprouting of cases germinated into a contagion.

Overwhelmed, one of Divina’s Italian colleagues threw in his masks and gloves and insisted that the hospital skip paying him because he will no longer show up for work. Not after the virus had claimed the lives of his friends and colleagues.

They were friends and colleagues of Divina Guerrero too. But for Divina, a devout Catholic and proud Filipino nurse, staying in the front lines was the only thing to do.

“I cannot back out because when I stood there as the sick arrived, I saw my family in them. My body was shaking, I was having goosebumps with what was happening to them. Whatever happens, if they were my family, I would not back out,” she said.

Guerrero lived in a 4-room house with her partner Freddie, their 23-year-old daughter Dienavie, and their 14-year-old son Denison. They have not exchanged embraces since February. Their neighbor next door tested positive for the virus. The only other Filipina nurse she knew in Bergamo tested positive, too, and had herself isolated home.

Her routine is as follows: she wakes up at 6 am, eats breakfast, and goes to work at 8 am until 3 pm. She has been skipping lunch more often these days. She could not bring herself to eat because of the deaths she has witnessed. As soon as she gets home, she takes a hot shower twice, wears a face mask, then holes up in her room and watches Eula Valdez teledramas on YouTube.

She does not remember the names of the shows. The storylines escape her memory. She just needed an escape. During her binge, Freddie would hand her a plate of food midway – pasta and bread are the staple. She then prays, then sleeps.

The scenes she has lived inside Policlinico have been etched in her memory. Patients heaved their final breaths alone. When the hospital staffers called the families to tell them of their loved ones’ demise, Divina held the phone toward the corpses for their last goodbyes. The calls could not be long, she said, because another patient had to take the space the dead had occupied.

For her own peace, Divina whispers her own prayers before sending the bodies off.

She has found refuge with fellow Filipinos in prayer. Most of the fellow nurses she knew were in Milan, where she worked from 1992 to 2000.

Every 3 pm and 8 pm, they said their vigils through Facebook, praying for the crisis to end. When the Vatican broadcasts an online mass, they watched together.

Finding solidarity among her fellow Filipinos, she felt pride in how many of them were risking their lives for a country they have not still considered their own. Nobody among them backed out.

They all left the Philippine yearning for something more, but they know that a part of them continues to be planted in their homeland. For Divina, this yearning came during the demand for foreign nurses in Italy boomed in the 1990s.

She still remembers barely understanding and speaking any Italian.

She knew her colleagues and patients cursed at her just by looking at their hand gestures (they would throw their hands in the air), and their faces (their eyebrows would furrow as they stared down at her).

She did not give much thought to it. She worked harder, and eventually gained their respect. They have even asked her to teach them English.

“We are here knowing that we are not exactly taking care of fellow Filipinos. We are taking care of people from different races. We do not turn away anyone, we do not turn away anyone all over the world,” she said.

She added: “The Filipino is hardworking and patient.”

Singapore

Monique Santos, 34, considers herself as one of the lucky ones. She works as a nurse in a prepared hospital in a prepared country: Singapore.

She came from a vacation in the Philippines, where she heard little news about the virus during her stay from October 2019 to January 2020. She was surprised to see Singapore was already preparing when she came home.

When she reported back to work in late January, her hospital already ordered staffers to wear face masks at all times and enforced a strict monitoring of all visitors in their premises. All but one entrance was shut off and everyone who came in had to disclose their health condition.

“What’s your travel history? Do you have a dry cough? Do you have fever? Do you feel sick?” the nurses would ask their visitors after taking their temperature through a thermal gun.

If they said yes to any of the symptoms, they were isolated.

Outside, the national government did its part by constantly informing Singaporeans through text messages, tightening border controls, preparing quarantine facilities, and distributing 4 face masks to each household in the city state of over 5 million people.

“Here at our hospital, what you are supposed to do and wear are laid out in a table,” Monique said.

From wearing just surgical masks, they have been ordered to wear N95 masks with complete PPE gear.

“We’re like astronauts now,” she said, describing her team.

Monique worked at the isolation tent steps away from the door of their hospital. The tent housed only two beds. Suspected COVID patients were not meant to stay there, Monique explained, because they would have to be turned over as quickly as possible to the Ministry of Health (MOH), limiting their contact with other people.

In this system, all suspected cases could not enter their hospital. The farthest they were allowed to go was the isolation tent, before the national government transfers them to more specialized treatment facilities.

They have not been overwhelmed. The government has been able to handle the patients through their own facilities.

Monique’s biggest complaint at work was that the tent was too hot. They have placed air conditioners, but it did not seem to give them enough cold air. She carries no fear or trauma.

“I am not afraid because COVID-19 is not the worst infectious disease that I have handled. The problem with COVID, for some reason, it became a pandemic, maybe because it was so infectious,” she said, explaining that HIV-AIDS was far deadlier.

COVID-19, she explained, can be contained through preparation and following guidelines.

“I am not afraid. Why? Because we have adequate PPE,” she added.

For their hospital, they could be punished for failing, as instructed, to wear everything on the table. “If you violate a rule, you will be dealt with accordingly,” Monique remembered being told. She did not want to know the punishment.

She feared that this was the reason why many of her fellow nurses all over the world, especially in the Philippines, have been infected. That they worked without protection.

As of May 7, over 1,800 healthcare workers in the Philippines have been infected, with the virus reaching many hospitals and even one of its premiere testing centers, the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine.

Frontline workers, Monique said, should refuse work if they are not properly protected – for the sake of their coworkers, patients, and their families. The burden of supplying the needed equipment falls on the government and the hospitals, she said.

Monique had once lived in this culture of martyrdom in the health sector. She worked in the wards and the emergency room of the Philippine Heart Center from 2008 to 2011.

There, she saw how people without money could die without treatment, pushing nurses like her to pay for their medicine. She also knows what it was like to keep patients in corridors because there were no beds available.

Monique was overworked as a young nurse. This was partly why she wanted to leave home. She said she has gone past it and wants to keep herself healthy.

Her health could spell life for her and her family. She is living with her husband, and she just gave birth to a daughter in the Philippines in October. She looks forward to coming home.

In epicenters and high-risk spaces, Filipinos far from home serve in the frontlines of the pandemic, scared and anxious, but bound by duty to care for those most vulnerable.

New Jersey, US

Mariles Mushet’s 8-year-old son called out to her in the middle of the night through the open doors of their bedrooms. “Mommy, I miss Cotto,” her son said, referring to their dog who had just died. “I need your hug – I can’t hug you.”

Seven days after intubating a patient who turned out to be positive for the coronavirus, Mariles started experiencing a sore throat, dry cough, shortness of breath, and a low-grade fever. As a nurse caring for patients in the intensive care unit of a hospital in New Jersey, Mariles did not need to get tested to know they were signs she had the coronavirus.

She quickly called her doctor to start her medication and soon after isolated herself at home from her husband and son. Alone, Mariles could only weep as she clutched her pillow, hearing her son’s call through the dark.

Mariles was only a year younger than her son when her father, then a crane operator in Saudi Arabia, died of a heart attack. Her mother, also an overseas worker, would also die of a heart attack years later, after a hospital refused to admit her until they paid P5,000. Mariles suspects this is why she wanted to enter the medical field.

Pursuing nursing, she added, was likewise part of a dream to be one of the first people in her province in Cebu to pursue advanced education.

Mariles recalled treating one patient in April who reminded her of her father. “I saw the resemblance and I cried while I was cleaning him. I told him, ‘You have to fight, okay? You have to fight!’ I wanted to boost my energy…I know they can feel and hear me but they just can’t talk because they have a tube in their mouth.”

Tears streamed down the patient’s face. “I knew he was listening.”

Mariles carries this care for others as her purpose. She said it is what brought her back to work at the ICU even after recovering from the coronavirus.

“I am privileged to go to the hospital and be with these patients at their side so they don’t die alone,” she said. “At least someone can hold them before they die. That was my fear when I was sick.”

With all 32 ICU beds of her hospital filled up, Mariles said she and her co-nurses are swamped as alarms constantly go off, signaling patients were in distress. The sound has been stuck in her head, waking her at night along with the image of patients whose faces turned blue from being unable to breathe.

The hardest part, she said, has been being unable to give patients and their families their final moments together – a response so essential when giving intensive care. Like in other countries, family members of patients cannot be in the same room as their loved ones to avoid getting sick.

Still, Mariles said her hospital found ways.

One April morning, she and her colleagues tried to wean a patient off being sedated to see if she could breathe on her own. The patient could not tolerate it and her heart stopped. Mariles quickly checked her patient’s monitor and saw her heart rate slow down from 70 pulses per minute, to 50, then 30. She checked her patient’s pulse and called for a code blue then performed CPR.

The patient came back after 3 minutes. Soon after, Mariles called the patient’s sister and explained what had happened.

“We got her back,” she told the patient’s sister who had been sobbing over the phone. But with that message, Mariles also told the patient’s family she did not know if it could happen again. The most she could do, Mariles said, was leave the hospital’s iPad in the room and the sisters to themselves.

“At least, you know, she said her goodbyes. I don’t know what happened to her after that. Hopefully she’s still alive but they said their last goodbyes, and that’s fulfilling,” she said.

Mariles puts on a brave face, a task, she said, that is possible because of her deep faith. “As long as I’m able to, I will do it… I have a purpose. That’s what pushes me to go to work and I am proud of myself.”

Tokyo, Japan

Excelsis Borbon grew up hearing frightening stories about the country he had decided on spending the rest of his life in – Japan.

His father lived through World War II as a child and told Excelsis about stories that haunted him – of Japanese killing Filipinos, including his father’s childhood friends when soldiers occupied their hometown of Cebu City in the 1940s.

“His friends who were captured never returned,” Borbon said.

He carried these stories with him until he graduated from nursing school in 2005 and was given the opportunity in 2009 to work as a nurse in the country he feared. Everything he knew about Japan revolved around the Yakuza, anime, and his father’s stories.

The fear was trumped by the allure of opportunity. He said yes to the offer, flew to Tokyo, and fell in love with the country upon arrival.

“My God, Japan is beautiful. The Japanese are so kind, so clean, polite, and kind. They always smile,” he said.

In Japan, everything was organized, but Excel found himself lost in its language. It continues to be one of the most complicated languages in the world with its own writing system for medical workers. Excelsis only learned the basics under training.

He found it so hard that he adopted a default response of “Hai, wakarimashita (Yes, I understand),” even when he really did not completely understand what he was being told.

This motivated Excelsis to study further. After working, he would go to Japanese language classes. A decade later, he still caught himself misunderstanding the Japanese when they spoke fast, but he could already keep up with speaking and reading.

When COVID-19 penetrated Japan and forced it to lock down, Excelsis was trusted to be one of the nurses to handle suspected COVID-19 patients in their hospital at their special ward.

Asked whether he was proud of his work, he said with modesty, “I think I’ve adopted the culture of the Japanese, because for us here, we are just doing our duty. Whether that’s a COVID patient or whatever virus, we are doing our job. We need to give 100% whatever case that is. That should be natural,” he said.

New York, US

Elrey Sinnung did not want to be a nurse. His mother suggested he study to become one, but he had preferred a desk job as an office man – maybe even an engineer. Thinking it was only proper he did what his mother wanted, Elrey graduated from the University of Santo Tomas in 2007 and found himself in the emergency room of the St Luke’s Hospital in Quezon City, catering to patients who suffered from a myriad of diseases.

In the flurry of people coming through the hospital doors, Elrey found something in him clicked. Each action-packed minute sparked a “sort of love,” he said. There was a thrill in knowing he could wipe down a patient, pierce needles through flesh, insert intravenous lines, defibrillate, and resuscitate people back to life.

Elrey thrived in the fast-paced environment, the flow of each action carrying him from one person to the next. But with a small salary and lack of viable work options in Manila, he decided to take the United States’ National Council Licensure Examination. He passed on his first try and left for New York after New Year 2016.

Elrey walked in knee-deep snow every day for a month to submit his resume to 30 health facilities. After working in a nursing home and a short stint at a New Jersey hospital, Elrey found himself back in his element at the New York Presbyterian/Columbia University Medical Center’s emergency room.

But in the weeks since the pandemic took over, Elrey paused – scared to walk through the doors of his hospital in Washington Heights, Manhattan.

New York, teeming with a population of over 8 million people, had become the epicenter of the United States’ coronavirus outbreak and his hospital, a battleground.

It was in January when he first heard of a new virus. Like his colleagues, Elrey thought it was probably like swine flu or Middle East respiratory syndrome – deadly but to a certain extent, familiar. Except unlike other diseases in the past, the coronavirus blindsided them as thousands of new cases packed hospitals.

“We were all shocked patients would die so soon after coming in. They’d come from their homes suffering shortness of breath. They could still speak. But as soon as they arrived in the hospital, they would rapidly deteriorate. Just two hours after talking to them, they’d needed to be intubated,” Elrey said.

He could hardly keep track of what seemed like an endless stream of patients coming into the emergency room one after another. It was the first time Elrey wondered if working was worth the risk.

“We’re not prepared. I’m not prepared. I don’t want to die.”

His family asked him not to go to work. Work, they said, was just work – and if making a living was his concern, they would help support him for as long as he needed. Elrey only had to keep going to work to know he needed to be there.

He imagined his patients as his family and colleagues and thought to himself, “If I quit now, and then everybody else quits, what will happen?”

But showing up meant recurring nightmares of treating patients when he was surrounded by a virus that could kill him. By the time he woke up, he felt drained even before having begun his day.

The struggle only became harder inside the hospital itself. Elrey and other health workers bore the weight of families struggling for ways to say goodbye. He recalled holding up the phone for one 60-year-old Hispanic patient, who spoke to his family one last time before being intubated.

“I’m here and I don’t know what’s going to happen but I just want you to know that I’m going to see you one way or the other,” he recalled the patient telling his family. Elrey thought of his father and for the first time since he started treating coronavirus patients, he cried behind his goggles.

In the weeks since the pandemic reached the US, Elrey said this was the way things run now. “You sort of get used to it to the point I had to shut down my humanity. Shut down my emotions because you won’t be able to finish your job and get things done.”

“With so many people getting sick, I ask myself how will this end? What can I do?” Elrey said. “It’s not just work. We have to survive.”

To temper his jitters, he’s set up an altar with a bible, rosary, and crucifix. “I’m not really one who is pious but now I pray and pray.”

Living away from his wife who is immunocompromised, Elrey calls his family over FaceTime every chance he gets and has given in to buying himself a guitar. He has resolved to teach himself, if only to keep sane.

Each morning on the way to work, he thinks of just turning around and going home. It would be easy. “I’m on my way but there’s still a chance to go back. You can call out – I’ve thought about that too,” Elrey said. Instead, he drowns out these thoughts to the sound of Foo Fighters’ “My Hero” playing on repeat.

“There goes my hero

Watch him as he goes

There goes my hero

He’s ordinary,” the song goes.

When he enters the emergency room, his heartbeat quickens to the beeping of ventilators and the sight of his friends rushing among patients. “We’re not superheroes, as much as people want to call us that,” he said.

“I’ll take a deep breath and say a quick prayer before I begin, although as soon as I take the first step into my area, I’m scared again,” Elrey said.

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Katrina Fadri is a nurse at a private hospital in Dubai tapped by the Emirati government to handle coronavirus patients. Unlike countries hit hard by the virus, Katrina said hospitals in Dubai have been able to keep up with the outbreak.

The United Arab Emirates, where she has been working as a nurse since 2012, was able to convince residents to cooperate with physical distancing measures intended to keep the virus at bay. Imposing lifestyle changes on the public gradually, instead of all at once – like closing some businesses, then schools, bars and restaurants, and later, public transportation – helped people to adjust their mindsets and avoid panic, she said.

Despite this, Katrina said she understood the virus was serious when the government decided to shut down schools as it sent the signal that children, not only adults, were vulnerable.

Since the crisis began, she said her hospital has luckily not needed to worry over the lack of PPE. Supplies remain steady and though she has more patients now, the government has also conducted mass hiring for health workers with short-term contracts that ensure they are well-compensated.

Conditions in Dubai are better than most countries, but Katrina admitted she still feels fear. The virus, after all, does not choose its hosts.

“Even with complete PPE, still at the end of the day, the virus is contagious. After work, you can shower but what if you touch something like the elevator button where the virus is still living on? All you have left is your own strength,” she said.

While this is the new reality for Katrina, she said it would be harder to stay at home than face the virus head on as a nurse. She is one soldier in the brigade of Filipino nurses employed by her hospital. She knows backing out of the battle is not an option.

“I’m still worried of course. My anxiety has become worse but then again, you come to a point where you accept you are a nurse. You are built for this and you need to help people. When you’re at this stage of a pandemic, it’s like that kicks in and you become selfless,” she said.

Working in a coronavirus ward, Katrina said patients are more stable than when they are in the emergency room or ICU, but that it is in these conditions as well, where they are most lonely. She recalled patients sometimes growing weaker the longer they stayed in hospitals, isolated from their families.

Treating an unfamiliar virus, Katrina said, she is still shocked by how some patients can deteriorate in a matter of only hours. “It’s hard because you do your part but their body just fails. Even if they want to fight, the virus kills them.”

Katrina decided she had to be brave not only for her patients but also her colleagues at the frontlines of the pandemic. With this mindset, she has decided she will show up at work each day.

“There’s no backing out for me…. If you lose resolve, people will feel that and you’ll just spread negative vibes. I’m okay. I don’t care how long (this lasts), as long as we fight because we have to fight for it. We want our lives back so we have to embrace this, accept what it is, follow the rules, be disciplined and pray,” she said.

For her fellow nurses, Katrina promised to be brave. “Let’s win this battle. See you after COVID.” – Rappler.com

Editors note: All quotations have been translated to English.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.