SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Aside from falling behind in mass testing, the Philippines has given assistance too little, too late to disenfranchised Filipinos under lockdown, even to those who need them the most – persons with disabilities.

At the beginning of the lockdown in mid-March, President Rodrigo Duterte promised that all struggling Filipinos could get aid – starting from the local government. The national government would step in, including top officials, once the local governments faltered and had a difficult time.

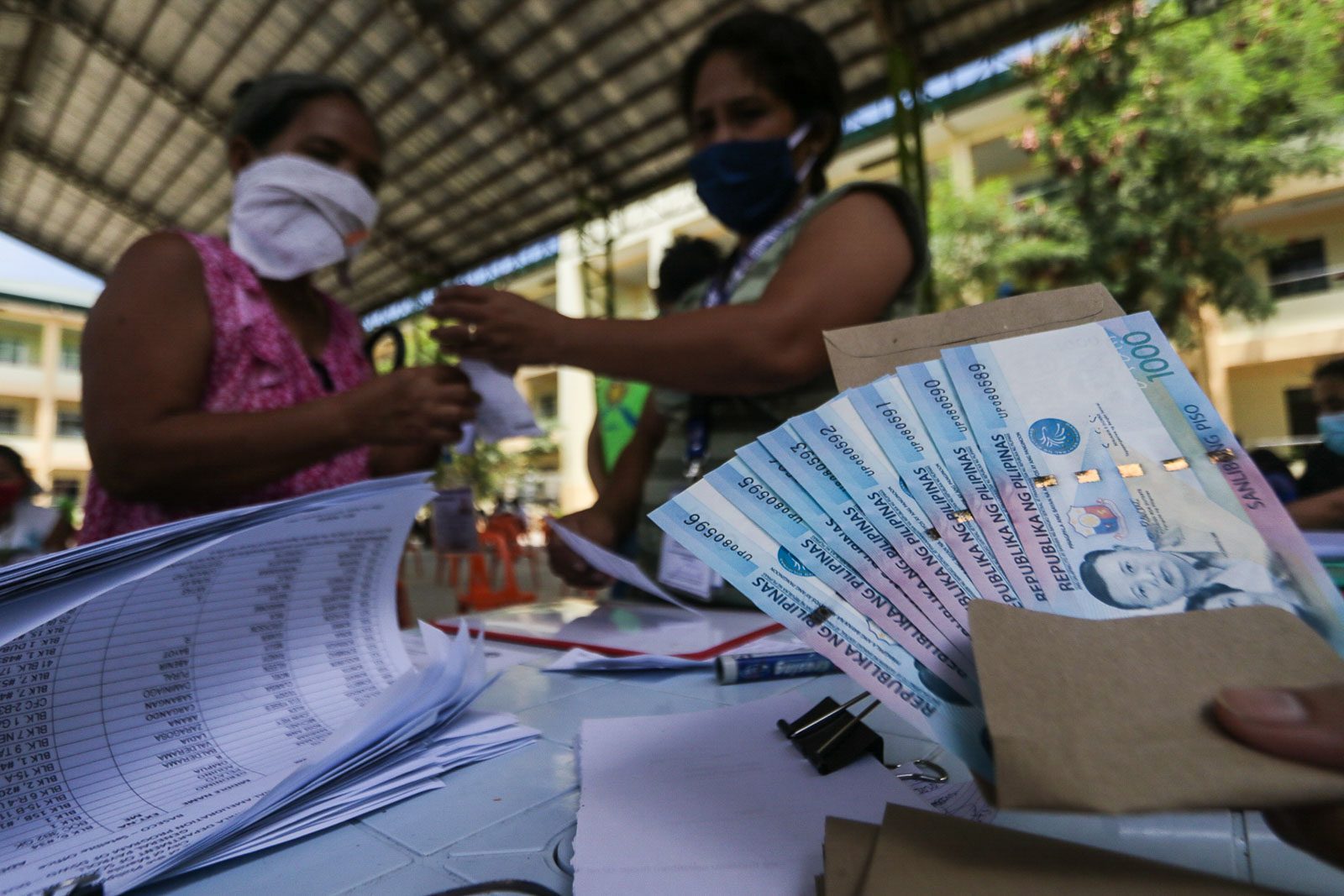

Weeks later came the promise of P5,000 to P8,000 cash subsidies from the Department of Social Welfare and Development’s (DSWD’s) emergency subsidy program (ESP), which was first proclaimed as being enough for poor Filipino families.

By using 2015 lists as basis for the amount of aid, however, the national government left local governments with inadequate social amelioration card (SAC) forms. They were also left to choose who among their “poorest among the poor” would receive them.

As of Tuesday, May 12, the DSWD reported that 16.6 million families have received cash assistance amounting to P93.6 billion.

The Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) reported that the distribution, as of May 11, was tantamount to over 1,200 local government units already completing their distribution of the emergency subsidies.

The stories on the ground, however, point to continuing discrepancies in distribution. Those who don’t need the assistance receive it, while those who need it the most don’t. Others are told to wait for extended periods of time or they don’t qualify because of inadequate documents.

Rappler spoke with 4 PWDs from different cities, and was told they have not received their share of subsidies.

According to DSWD Assistant Secretary Joseline Niwane, one of the top officials in charge of implementing the ESP, the problem stems from LGUs.

“In [ESP], we are giving LGUs the responsibility to select who really needs it, with the assumption that they know their people,” Niwane said.

Niwane said those who haven’t been included in the list of LGUs should tell their local officials so that they could be included in the next batch of beneficiaries. Most of those excluded, however, said they no longer have the luxury of waiting as they, along with their families, have already become hungry.

A house of abandoned priorities in Manila

Joanna Grace Cayabyab, 31, lives under the same roof in Gagalangin, Tondo 2 as 4 other people who were promised they would be first to receive government cash assistance. They have not received any.

One of them is her own son, Sky Mendoza, an energetic 3-year-old who screamed in the background with joy as his mother spoke on the phone for an interview.

“Mommy! Mommy!” the baby shouted as Joanna’s cousin, Carissa, attempted to distract her child.

Sky has multiple congenital anomalies in his body – his esophagus is not connected to his stomach and he does not have a hole that serves as his anus.

Joanna feeds Sky with blended vegetables, fruits, and meat through a network of tubes that pump food into his stomach.

In other parts of their home live Joanna’s grandmother, already 92 years old, and her 60-year-old uncle. Carissa, like Joanna, is also a solo parent with two children. (READ: ‘Walang wala na’: Poor Filipinos fear death from hunger more than coronavirus)

Before the government shut Metro Manila’s borders and ordered millions to stay home in mid-March, Joanna earned through her own stall in cyberspace.

She would buy bedsheets and curtains from Divisoria, prop up her cellphone on a stand in their cramped home, open Facebook, then press live. It was a selling show that gave her from P300 to P1,000 a day.

Two months since the lockdown, all of these have practically evaporated. They have managed to get by, so far, only by scrimping on food.

They have received relief packs thrice from the Manila City government and her barangay, but according to Joanna, these have been far from enough.

“Am na nga lang ang ginagamit sa bata (We’re only using rice water as milk for the child),” she said.

Manila Mayor Isko Moreno approved a program to give all families in the capital P1,000 in cash aid on April 5. No one in their house received a single peso. They are not on the barangay’s list, she said.

She heard they were qualified for the national government’s subsidy and went to the barangay. She was told they were all qualified for the assistance, but that there were no forms left for them.

They were told to wait.

Weeks passed. They have started eating only after 5 pm to save on food. She heard that other relatives who live in other parts of Tondo have received cash aid. She has been texting her barangay officials to get updates but has repeatedy been told to wait.

“Sana alam din ng gobyerno yung mga mas nangangailangan (I wish the government knew who are more in need of help),” she said.

Helplessness in Baguio City

Reynaldo Tabrilla, 42, has no fingers in both hands and doesn’t have a right foot, but he loves playing basketball and works as a technician. He fixes television sets and builds houses.

His workflow is simple. He stays at home and waits for a call from anyone in Baguio City then he rides a jeepney to their homes and goes to work. He has learned to live with his disabilities.

“I can walk like a normal person. I worked to do this. I trained my body so that I don’t burden society,” Reynaldo said in a phone interview with Rappler.

Reynaldo is single. He lives with Romeo, the husband of his sister who died in March 2019, and their daughters Catherine, 26, and Camille, 20. Romeo works as a driver for a government health center.

After the country was placed under lockdown, Reynaldo found himself most vulnerable. He could not leave home to play, and could not even go to customers who needed their TV sets repaired.

For the first time in a long time, too, he felt hunger. He said he has so far been fed through the relief packs handed to him by the Baguio local government but they are almost running out.

Romeo has been working to place food on the table for everyone too, but Reynaldo does not want to depend on him further.

He knows his best option is to claim the cash aid promised by President Duterte, but Reynaldo could not figure out how he could claim his share.

He walked to their barangay center to ask whether he was included in their list of beneficiaries. He wasn’t. Barangay workers asked for his signature and told him to wait for their call.

Baguio City is already on its way to easing lockdown rules and implement a “transition period” and yet Reynaldo’s barangay officials have not called him since the enhanced community quarantine period started.

The so-called City of Pines has been praised for its lockdown measures, but Reynaldo believes it still needs to work on its aid distribution, specifically when it comes to working with barangay officials. He noted that residents who were more well-off were able to receive aid ahead of him.

“The problem is with the officials on the ground, the frontliners. I have no problem with the mayor. But I think the problem is with the barangay,” Reynaldo said.

Asking the disabled to work in Antipolo City

The right leg of Rodel Raquiza is inches shorter than his left, a disability caused by polio. He could not stand straight nor walk properly, but poverty has driven him to become a construction worker.

He could not afford to stay home, now that he has Josephine, his live-in partner, and Princess, their 6-year-old daughter, to feed.

“I am the only one who makes a living for us three,” he told Rappler in a phone interview, explaining that he did not allow Josephine to work because she was a “small” woman.

“I cannot depend on others, especially when we live at a time of poverty,” he said in Filipino.

They live in Antipolo, Rizal, but Rodel works in the neighboring town of Teresa, making between P200 and P300 a day. After the lockdown was imposed, he found himself without work.

He found hope when President Duterte promised that everyone who needed help would get it, if not from the national government, then from barangay officials.

Rodel’s household has received relief packages from the local government and the local church, but they quickly ran out. Debts to market stalls have piled up and he needs cold cash to pay them and procure more food for the dinner table.

He heard that he was qualified for the government’s cash subsidy program so he went to their barangay hall where he recalled being interviewed by a social worker.

He was not given a SAC form because he was not a registered voter in the area and he did not hold a PWD card. (READ: [ANALYSIS] Challenges facing social amelioration for the coronavirus)

“I was told I was qualified but I was not a registered voter,” he said.

The rejection goes against the government’s policy of distributing the cash aid to anyone qualified to receive aid.

Before moving to Antipolo, Rodel worked in Teresa 4 years ago and has not found the time to renew his voter registration in his new locale. Neither has he had the time to register as a PWD.

Working as a PWD construction worker already took much of his time, he said. He was not given advice about what he could do except to get his papers done before getting aid. Yet he knows of neighbors who are not even PWDs but have received help.

“I wish we were fair for all now. I wish those who would be given are the ones who really need it, not those who could even afford to slack off,” he said in Filipino.

Nothing left in a Quezon City home

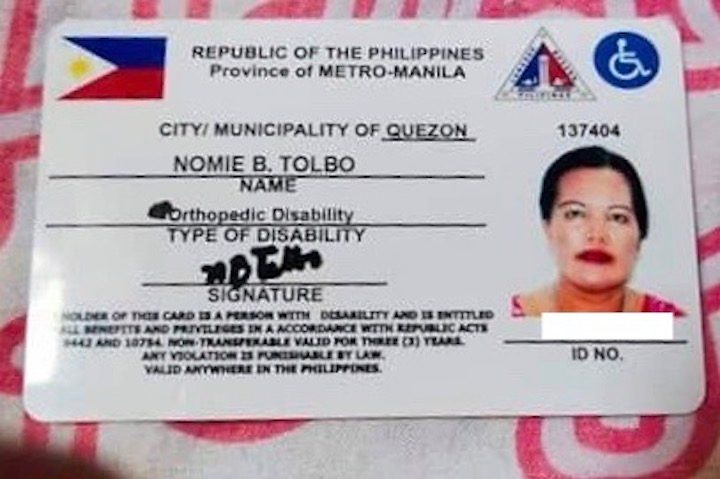

Nomie Tolbo, 43, has a left hand that forms a half fist, her fingertips stuck to where the base of her fingers meet her palm.

With her condition, it’s been practically impossible for her to find a job, that’s why she decided to stay home while her husband Erson works as a construction worker to provide for their family.

She and Erson have two mouths to feed: 10-year-old Trissa and 7-year-old Venice.

Since the lockdown, they have not been able to earn anything. Her husband could not earn unless he worked. They have spent their savings as they wait for help.

From March to April, they’ve depended on relief packs given by the local government. But beginning May, they have started to run out of supplies. Nomie remembered that the government promised them cash aid.

She recalled that they were supposed to be visited by either their barangay officials or a social worker from the DSWD, but none have come knocking. She decided to go to the officials herself during the first week of May.

“We went to our area leader, he said they had nothing on hand. He told me to go to the barangay. I went to the barangay. The barangay told me there were no more forms. I spoke with the barangay captain and he said we should wait,” Nomie told Rappler in a phone interview.

The officials just photocopied her ID and told her to wait for their call.

She has two other neighbors who are also PWDs with IDs, and both still haven’t received even a form. She heard of other neighbors who weren’t PWDs but who already got their share of cash aid.

“Our savings are gone. We have spent all of it. What’s disturbing is that our other neighbors have gotten help. Why can’t we be afforded the same?” she asked in Filipino.

The Philippine government is now focused on cautiously easing quarantine rules to allow more people to return to work while preventing the spread of the virus. For PWDs like Nomie, Reynaldo, and Roy, all they ask is that they not be forgotten. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.