SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – “I can tell you now that I will provide leadership.”

Rodrigo Duterte made this closing statement at a presidential debate in Cebu City, around a month before winning the Philippine presidency by a landslide.

With still thick black hair swept to the side like an altar boy’s and a brown face not as lined with cares, the then-mayor and presidential candidate promised Filipinos decisive leadership.

Observers called it “leadership without details,” a promise to get things done even if he could not explain his plan. A doer, not a talker. A man with a vague platform but tons of political will.

Fast-forward to June 2020, an older, exhausted President Duterte is locked up in Malacañang, confronting the defining crisis of his presidency – the coronavirus pandemic.

But when decisive leadership was needed the most, Duterte failed to deliver.

A joint effort by Rappler reporters, involving perusal of official documents on the Duterte government’s virus response and talks with multiple sources, showed that a lack of quick, effective leadership in the critical months of January to February cost the country lead time that could have cushioned the blow to the economy and rise in infections.

Where is the Philippines in the pandemic?

As Duterte nears the 4th anniversary of his presidency, 5 months have passed since the Philippines recorded its first coronavirus case, a Chinese woman from Wuhan who arrived in the Philippines on January 21.

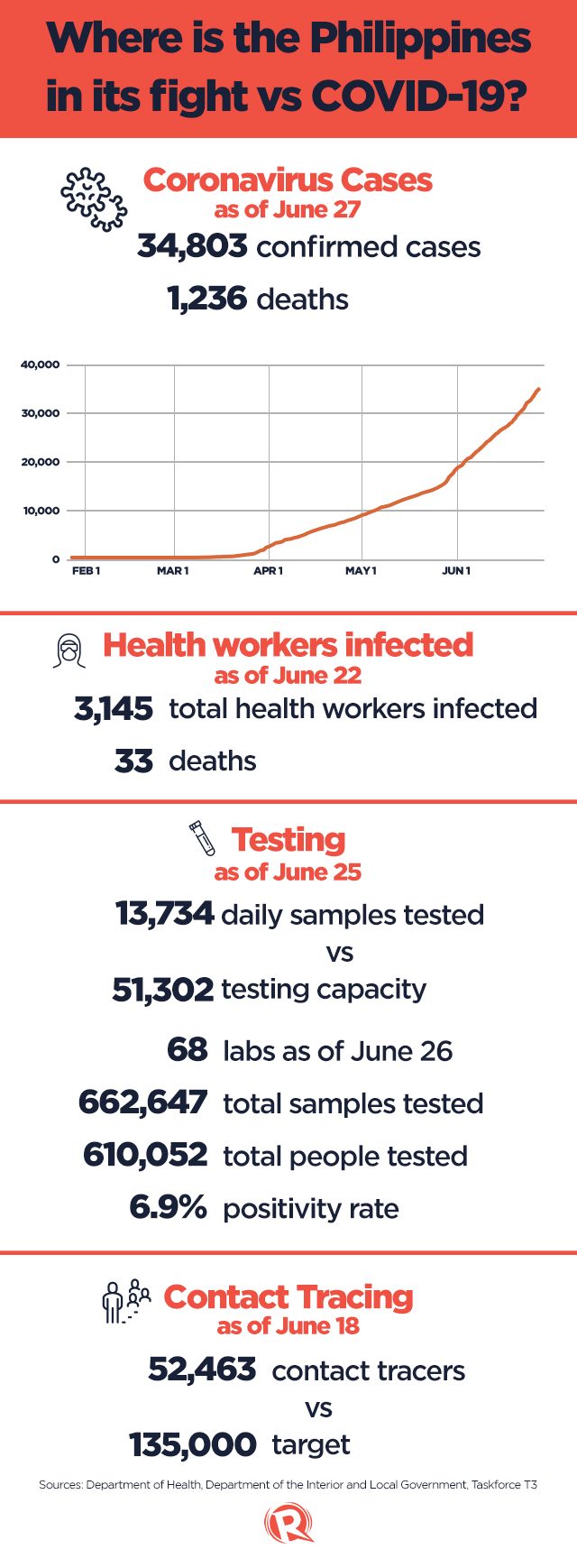

After 3 imported cases in late January and no cases reported in the weeks that followed, a 62-year-old man walked into the Cardinal Santos Medical Center on February 25 hot with fever and reeling from a headache. He became the first confirmed case of local transmission of the virus, meaning he had somehow gotten infected inside the country.As of June 26, there are over 34,000 confirmed cases in the country. Over a thousand have died. Because the government was able to ramp up COVID-19-dedicated facilities, the country’s overall critical healthcare capacity has not yet been overwhelmed (it’s a different story when you zero in on localities, like Cebu City where capacity is almost maxed out).

We’re doing better in terms of testing, ramping it up from 0.18 tests for every thousand people in early April to 4.75 per thousand on June 18. This is better than Indonesia’s 1.4 rate as of June 21 but worse than Malaysia’s 21 and Singapore’s 58 (check Our World In Data for more on this).

Still, the Philippines is not testing enough. Despite boasting that the country’s 66 labs can collectively conduct a maximum of over 50,000 tests, the daily samples tested struggled to surpass a high of 14,519 samples tested on June 17.

Hampered by operational issues that include lack of supplies and personnel, the average number of samples tested daily hover between 10,000 to 14,000 – a figure that falls short of the targeted 30,000 daily tests the government first aimed for by the end of May.

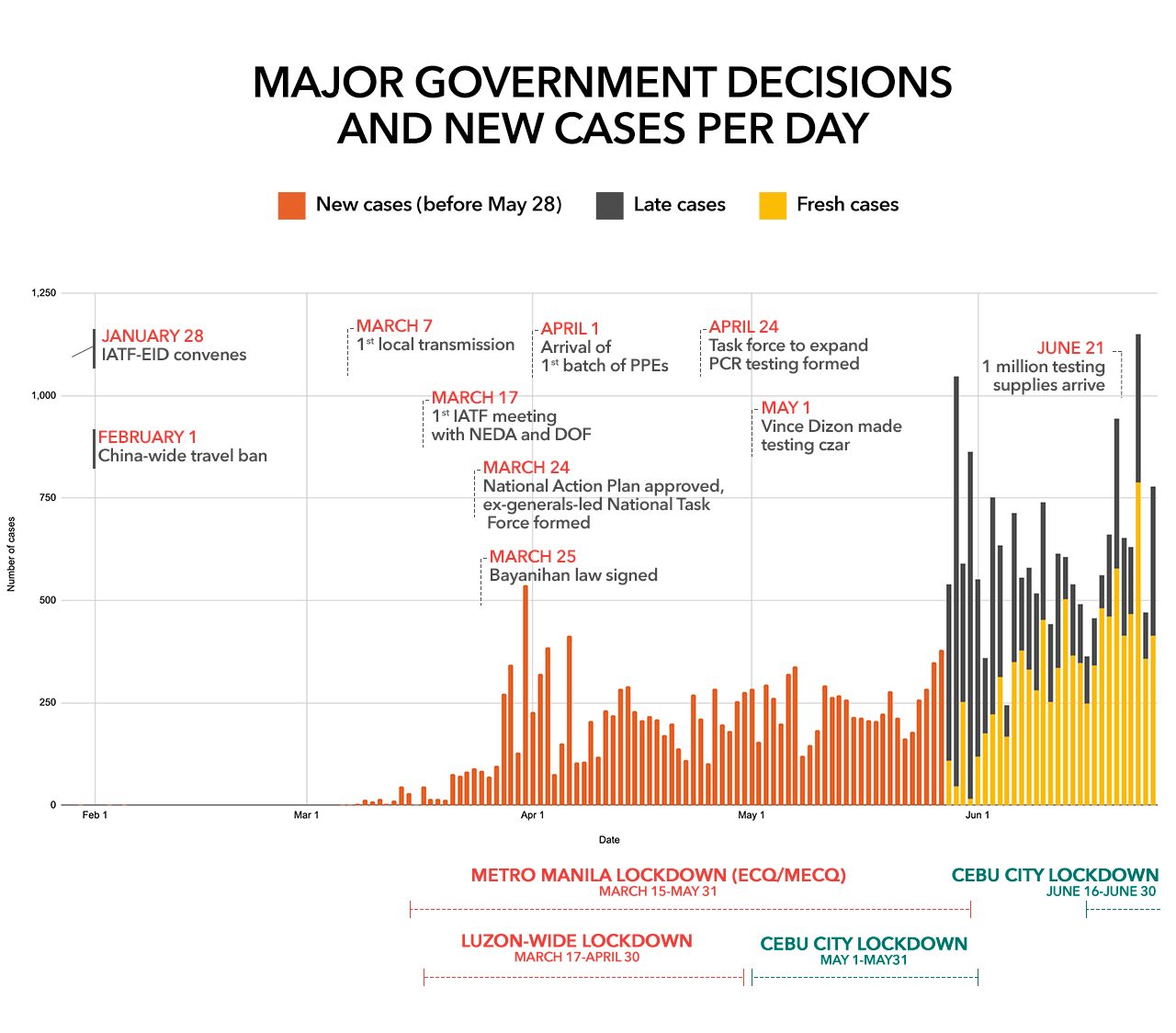

Lockdowns helped lessen a rise in cases but this was only a reprieve. From some 200 to 300 new cases a day during lockdown, figures spiked to between 500 to 1,000 a day as more people ventured out following the easing of restrictions meant to save a crippled economy.

The Philippines’ number of cases look small when compared to those of the United States and Europe, something Presidential Spokesman Harry Roque has been quick to point out when faced with criticism.But we are far from the achievements of some of our Asian neighbors who have managed to flatten their pandemic curve despite facing the same problems – urban congestion, lack of resources, and economies closely linked with China, the virus epicenter.

Decisive leadership among Asian neighbors

Vietnam, a developing country with roughly the same population, managed to contain their infection rates, largely due to early action by their government in January and February. Proactiveness saved thousands of lives and even their economy, which is among the few in Asia still expected to grow.

Early action and efficient implementation meant Vietnam was able to ramp up response where it mattered – testing, isolation, and treatment.

By April, Vietnam had 112 coronavirus testing labs from just 3 in January. In the same time period, the Philippines was only able to grow its number of labs from one to 15. We now have 66. Like the Philippines, Vietnam couldn’t immediately afford to test large numbers of people, so instead, they boosted their contact-tracing, even reaching the 3rd circle of a case’s contacts, one of the defining characteristics of their response. When hot spots emerged, the government locked down specific localities. “Simple stuff done very, very well… The majority of this effort has been good organization,” said Hanoi-based infectious disease doctor Guy Thwaites in an interview with Rappler editor-at-large Marites Vitug.“Vietnam would not have been able to do what they’ve done unless they acted early,” he added.

Vietnam’s nationwide lockdown lasted only 21 days. Metro Manila, meanwhile, was under lockdown for 78 days (from March 15 to May 31, the last day of modified enhanced community quarantine). An entire region, Luzon, was under lockdown for 45 days.

But while Vietnam is slowly emerging from the crisis, achieving consecutive days of zero new cases, the Philippines is breaking records on single-day rise of cases (breaching the 1,000-mark on some days).

This was expected, since the Duterte administration decided to ease restrictions despite failing to contain the virus spread. It was a hard but understandable decision, given the massive damage to the economy and loss of jobs. The government simply had no choice.

What happened in January and February?

Not having to make this terrible choice would have been the prize of early, decisive action in the critical months of January and February.A look at the 48 resolutions of the Inter-agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) shows that the first meetings of key officials did not involve discussions on mass testing, preparation of isolation facilities for persons other than repatriates, or a strategy for contact-tracing.

IATF meetings from the first one on January 28 to the 9th on March 3 were all about travel restrictions and the testing and isolation of Filipinos coming from abroad.

It was only on March 9, or over a month after the first confirmed case, when the IATF discussed internal measures to shield the domestic population – class suspensions, ban on mass gatherings, and encouraging work-from-home arrangements. The country had 24 cases by then.

It was a textbook response to the stage the outbreak was in, health sources told Rappler. The small number of cases dictated a strategy on “containment” or the effort to keep the virus out of the country and isolate individuals who could possibly be infected.

For the Department of Health (DOH), this meant signaling public and private hospitals to strengthen infection prevention and control measures and advising them that patients seeking treatment or consultation for the coronavirus should be reported to the agency’s epidemiology bureau.

Further advisories on methods to contain the virus in workplaces, schools, communities, hotels, and observing proper home quarantine were also issued – signs it had come up with the needed protocols and guidelines. Yet the effort would fall short of the public’s attention as greater focus was placed on calling on the public to remain calm over emphasizing that these written measures had been put in place and should be observed.

The department’s issuances would not be clearly understood and acted upon by both national and local governments during the critical window in February when cases remained low, former health secretary Manuel Dayrit pointed out. Dayrit had led the DOH in the control of SARS in 2003.

The situation left workers on the frontlines in both public and private sectors – health workers included – not as prepared as they should have been.

“I believe that the DOH did come with written protocols and guidelines in late February and March. But it is not enough to release written issuances. It was critical that the issuances be understood and acted upon throughout the whole national and local government bureaucracy…. It was a huge training and logistical challenge! No, as far was I could tell from discussions with local government officials and private sector colleagues, I don’t think those needed preparations were undertaken satisfactorily,” Dayrit said in an interview with Rappler.Even when it came to containment efforts, the Duterte administration focused more on controlling messaging rather than taking into consideration the virus’ potential to become a full-blown threat.

While lawmakers called on the DOH to recommend a travel ban as a “prudent” decision, Health Secretary Franciso Duque III argued before Congress on January 31 it would be “tricky” to single out China when other countries reported cases of the coronavirus. Instead, he said, they would “commit to take this into consideration.”Duque was merely echoing the President’s response the night before as Duterte told reporters he was “not inclined” to ban travelers from China as it would be “unfair.”

The decision would be costly as 2018 data from the International Air Travel Association placed the Philippines among the top 15 countries receiving travelers from 18 high-risk cities in China, including Wuhan. Philippine tourism statistics had also recorded some 1.7 million Chinese tourists visiting the country in 2019, making them the second largest group of foreign tourists following South Koreans. But in two days and amid public outcry, Duterte appeared to have changed his mind, authorizing Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea to finally declare a China-wide travel ban on February 1.Blindspots and bottlenecks

The shortfalls cascaded to crucial areas of response including contact tracing and testing.

Several health sources Rappler spoke to said the DOH relied on the Research Institute of Tropical Medicine (RITM) to carry out testing when more labs should have been equipped earlier.

The RITM was spread thin even further as it was tasked on February 7 to train other laboratory personnel and aid in accrediting new labs across the country. The burden would only be shared by the University of the Philippines National Health Institutes two months later on April 16, according to a DOH circular.

Meanwhile, there was a gaping hole in the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a critical agency because it alone could approve rapid and reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test kits, ventilators, and personal protective equipment (PPE) sets for use in the country.

For nearly a year, Duterte failed to appoint an FDA director general after firing its former head, Nela Charade Puno.

At a time the need for such supplies was urgent, the FDA had only an officer-in-charge, health undersecretary Eric Domingo. An OIC’s powers are confined to ensuring day-to-day operations. Domingo also still functioned as a health undersecretary.

On February 6, Duterte finally appointed Domingo to the post. Domingo received his appointment papers on February 9 and assumed the post a month later, on March 9, after completing a turnover of his responsibilities at the DOH. Since then, the number of registered test kits has grown to 178.

But the delayed accreditation of labs, coupled with limited tests at the onset of the outbreak, resulted in a testing effort caught “flat-footed,” as described by another former health secretary. Testing was unable to keep up with the increase in cases.

When it came to contact tracing, similar obstacles occurred.

As early as the end of January, when the first few cases of the coronavirus were recorded in the Philippines, locating people who were potential spreaders of the disease was one of the earliest tests of the Philippine health system’s capability to contain the virus. The task proved too difficult for the DOH’s epidemiology bureau.Spread thin by two previous outbreaks that included measles and the resurgence of polio – a disease that was not seen in the country for 19 years – the tiny division in the health department struggled to keep up.

Contact tracing efforts were further frustrated by the lack of proper coordination between the DOH, Civil Aeronautics Board, and the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines to locate all passengers on a flight that included a woman and man from Wuhan, who turned out to be the Philippines’ first case and death, respectively.

A Senate hearing on the matter on February 4 revealed that only about 17% or some 50 of 331 passengers on the flight were located. By that time, the virus had made inroads in the country as the two travelers from Wuhan traveled to Cebu, then Dumaguete, before arriving in Metro Manila where they were hospitalized.

One thing public health experts note the country was able to achieve throughout the lockdown was to strengthen the health system’s capacity to cope with coronavirus cases. Most hospitals early in the quarantine averted a scenario where wards and intensive care units would buckle under a deadly surge in cases.

But despite most warning signs, the DOH and its leadership took a slow approach to mitigation or controlling the spread of the virus in the country.

Health sources told Rappler that though there was a lack of knowledge on just how infectious the coronavirus was, the agency could have evolved more quickly and erred on the side of caution. What it failed to plan for was a worst-case scenario as the outbreak quickly escalated into a pandemic.

Duterte’s ‘overkill’ response: M.I.A.

At a time when the government should have been preparing for the worst, Duterte was downplaying the threat, telling the public on February 3 that “everything is well” and there’s “nothing really to be extra scared of” because the virus would die a “natural death.”He had just emerged from an emergency meeting on the coronavirus where he said his Cabinet decided to procure more “supplies” for the crisis.

Asked by a reporter if the government was already looking for quarantine facilities in preparation for a worst-case scenario, Duterte said, “Hindi, hindi pa ngayon. Eh dalawa lang ang namatay eh.” (Not yet. Only two have died.)

Nowhere to be found then was Duterte’s famed tendency to “overreact” and implement “overkill” policies in the name of protecting Filipinos. In the past, some had praised him for such responses – like threatening “war” against Canada for their stranded garbage or shutting down Boracay Island due to pollution. His supporters said this is classic Duterte style governance that may be over-the-top, but at least, gets things done.

A presidential intervention in January and February could have sped up preparations in testing and lab accreditation or given a greater sense of urgency to contact tracing.

“He was not able to live up to his promise of being decisive, fast, efficient,” said political science expert Ela Atienza.

One reason could be that Duterte and the DOH relied too heavily on the World Health Organization.

“It’s always good to go by the WHO… They have all the inputs and they would know what to do. We go by the regulations that will be given out by the WHO. We cannot act on our own,” he told reporters on February 3.

It was an early indication that Duterte was out of his depth when it came to the crisis at his doorstep.

For most of February, Duque was also constantly downplaying the threat because, at that point, the government had only confirmed a few cases, an imported one at that.

In contrast, Vietnam did not wait for the WHO. It closed its borders on January 24 when the WHO was still advising against travel restrictions. It ordered mask-wearing, when WHO was still saying it was unnecessary for healthy people – an issue they would change tunes on 5 months later.

Still, Malacañang said the Duterte government has done a “fairly good job” in dealing with the pandemic.

Asked why the Philippines has not managed to catch up with other countries in stemming a rise in cases, Roque did not give a direct answer and instead said the country would be in even more dire straits if not for Duterte’s lockdown.

“The whole world is far from beating COVID-19…Millions would have gotten sick if we did not impose lockdown and a minimum of 200,000 would already be dead if not for the lockdown,” he said on Thursday, June 25.

‘Double tap’

Duterte’s unique contribution to the effort finally came on March 24 when he formed the National Task Force Covid-19 (NTF) and assigned his trusted retired military generals to lead it – Delfin Lorenzana, Eduardo Año, and Carlito Galvez Jr. Before this, Duterte had largely merely approved recommendations by the IATF.

Not many people are familiar with the NTF. This is no surprise since, technically, the NTF is redundant. The government already had an outbreak response implementing body in the IATF, created through a Benigno Aquino III-time executive order. The IATF (note, it also has a “task force” in its name) was only made into a “policy-making” body by Duterte when he made the NTF the implementing body.

The difference between the two is the IATF is chaired by the health secretary while the NTF is led by retired generals in Duterte’s Cabinet.

It’s a typical Duterte move since he’s done the same for past crises – like the Boracay shutdown also overseen by retired soldiers. Duterte says he prefers military men because of their obedience to orders and adherence to the chain of command.

The NTF was created so the pandemic response could be done the Duterte way.

But while Vietnam’s Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc created his National Steering Committee (led by his deputy minister and two deputy health ministers) a week after their first positive case, Duterte formed the NTF two months after the Philippines’ first case.

There are consequences to appointing retired generals to handle a health crisis. Clinical science and “tactical” considerations could go head to head, which is what played out in a Zoom meeting on rapid testing held in late April.

An official present at the meeting said the NTF heads were “trying to put their opinion over and above the doctors.”

DOH doctors in that meeting were arguing against the use of rapid tests because of the danger of false positives and false negatives. By that time, however, Duterte, the commander-in-chief, already said he would “take the risk” in purchasing rapid tests.

National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr, another retired general in Duterte’s Cabinet, insisted that the uncertainty of rapid test results could be fixed by just doing the rapid test twice.

“They said, well we could always ‘double tap’ it. It’s a military term. If you want to be sure that you hit the target efficiently, you double tap. Bang, bang. So if the first test is negative, then after a few days or a week, double tap it, and it might come out negative again,” said the official.

The DOH itself, along with the Health Technology Assessment Council composed of medical experts, had opposed relying on rapid tests. But the limitations on resources for the RT-PCR tests, which Malacañang agreed was the “gold standard” for testing, led the NTF to prescribe double rapid tests in certain scenarios.

The danger of this was soon revealed when Balik Probinsya beneficiaries who tested negative in a rapid test in Metro Manila tested positive after a PCR test conducted in Leyte. They became the first cases in their hometowns. The Balik Probinsya program, created by Duterte himself in support of his aide Senator Bong Go, was eventually suspended.

The government would eventually require PCR tests for returning overseas Filipino workers and locally-stranded individuals traveling back to their hometowns.

The Philippines is in a better position than it was back in February in terms of COVID-19 treatment facilities, PPE sets, and testing, thanks to IATF and NTF officials, the private health sector, and the businesses and civil groups that chipped in.

But the country now plays catch-up against odds that could have been made smaller with early, decisive action from the most powerful man in the country. – with reports from Bonz Magsambol/Rappler.comAdd a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.