SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Charley Santa Maria, 33, got on the bus to Kalinga province with her friends and their children for an out-of-town birthday celebration of one of the kids. It wasn’t long before the beautiful sites they were seeing along Halsema highway, Mountain Province, ended on February 7, 2014. The GV Florida bus with 45 passengers fell into a 400-meter deep ravine.

In most cases like this, drivers point to mechanical failure as the cause of the accidents. A closer look reveals a more sinister reason. Corruption thrives inside the government agencies tasked to ensure safe public travel. It is so rampant and pervasive that any vehicle, in whatever condition, can be given the right to ply the roads and become rolling coffins for unsuspecting passengers like Sta Maria.

The two main government bodies tasked to manage and regulate land public utility vehicles are the Land Transportation Office (LTO) and the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB).

These two work hand in hand: LTO registers motor vehicles and issues licenses to drivers, while the LTFRB enforces and monitors their compliance with policies, laws, franchises, and regulations. Unfortunately, insiders say, they also work together in fraud and bribery that continuously result in passenger deaths and injuries.

The number of deaths involving public utility vehicles in the Philippines is alarming. The Philippine National Police-Highway Patrol Group reported 15,572 vehicular accidents nationwide from January to December 2014. In these, 1,252 people died while 9,347 were injured.

A couple of months before the GV Florida bus accident, a Don Mariano bus fell off the Metro Manila Skyway in Parañaque City, killing passengers, on December 13, 2013.

In February, a car was pinned by two public buses along EDSA. Fortunately, the driver of the car survived.

Modus operandi at the LTFRB

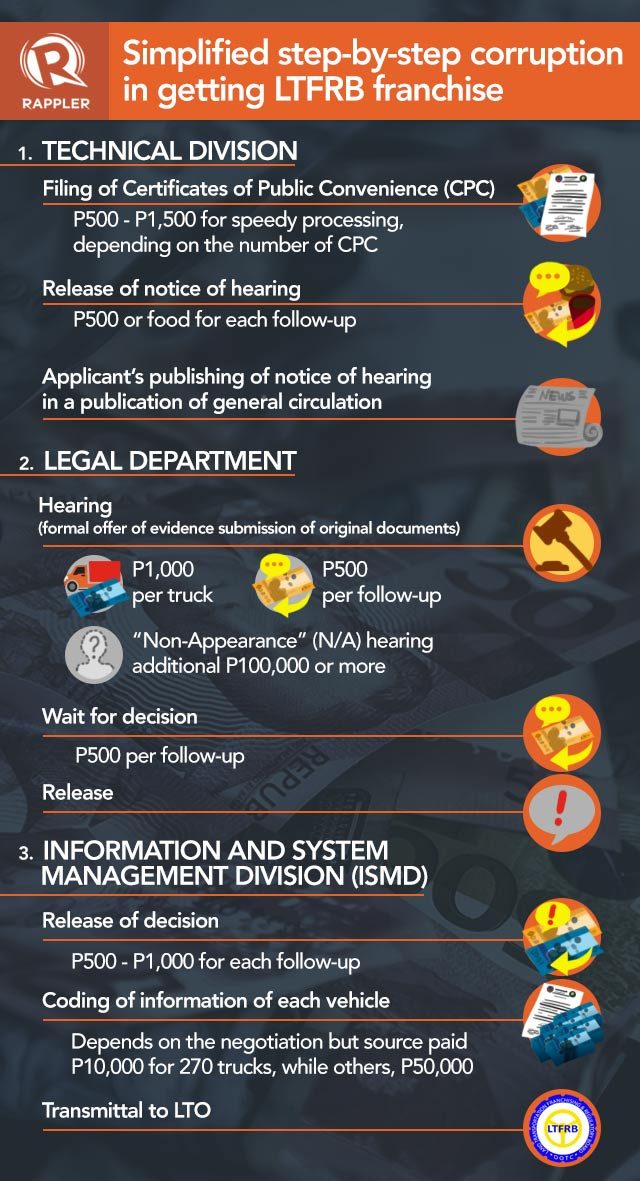

To operate a public utility vehicle (PUV) legally, an operator needs to get a franchise. He must apply for a Certificate of Public Convenience at the Technical Division of the LTFRB. The CPC is an authority granted to a private group or company that seeks to provide services to the public.

After that, a notice of hearing will be given. Applicants need to publish this notice in a newspaper of general circulation within 5 days before the hearing date. Next, the Legal Department will conduct a hearing, where formal offer of evidence and submission of original documents are done. Finally, the applicant waits for the decision. The LTFRB website says it will only take 45 days before a decision is issued.

Rica Lim* is a liaison officer for a company. One of their clients is a trucking company with more than 200 units. Part of Lim’s job is to secure franchises and other documents from the LTO and the LTFRB. She knows the ins and outs and has a front row seat to corruption at these agencies.

Since she applies for franchises by bulk, she said some employees would hint at the need for a bribe.

“That’s why there are many buses, vans, and other PUVs that get franchises even if they have dilapidated and unserviceable units,” Lim said.

Lim said their company has spent close to P1 million to represent one company’s application for franchises of 270 trucks at the LTFRB. Every step of the application, she said, will bleed you dry.

Step by step

For the first step – filing of CPCs – she pays P500 to P1,500 for speedy processing. She goes back and forth to the Technical Division to follow up on the status of the application and the notice of hearing. She has to do this religiously so as not to miss the 5-day window for the publication. If she misses that, the application will be voided and she will have to repeat the process. Each time she asks for a follow-up, she has to pay P500 or bring food for the people she deals with.

“Whenever I transact with them I always make sure I have at least P20,000 to P600,000 with me,” Lim said.

Next, she pays the LTFRB lawyer assigned to the hearing at least P1,000 per truck. For her last transaction, she paid P162,000 for 162 trucks. She said, though, this is a low price compared to what others would pay. She does another series of follow-ups after, each time shelling out P500 to P1,000.

Lim said that for a higher price, many operators and liaison officers avail themselves of the so-called “N/A” or non-appearance hearing. The same “N/A” operation applies to buses, vans, and even jeepneys.

“All they have to do is submit the complete documents and the [agency] employees will take care of everything until the favorable decision is released. Operators and liaison officers usually pay P100,000 to officials of the Legal Department on top of the P1,000 fee per truck,” she said.

Meanwhile, the Information and System Management Division handles the release of decisions, coding of information on each vehicle, transmittal of franchise information to the LTO for vehicle registration, and the individual printing of details of each vehicle.

She added she paid P10,000 for the encoding of 270 trucks. Her company was practically left with no option because they would miss the deadline if they waited for the usual process. Some, she said, pay as much as P50,000 to get ahead.

Contrary to what the LTFRB claims on its website, Lim said the issuance of decisions takes several months and not 45 days. “If you want your papers to move faster, pay more,” she said.

The corruption in the agency is so widespread that even low-level employees have their own “business.” Lim said she gives a minimum of P50 to the security guards in addition to free food from the canteen for easy access to the two most important divisions: the legal department and ISMD.

Not an inside job

LTFRB Chairman Winston Ginez denied corruption allegations involving his people. Ginez blamed fixers or unauthorized liaison officers for the illegal activities.

“These are not employees…There are people that are used to assisting applicants, offering their services (to them). They make the picture (of the process) look hard… so instead of going directly to us, the applicants pay fees to them,” Ginez said in an interview with Rappler.

Ginez, however, admitted he has heard of the “per unit” payment scheme in the agency but insisted his people are not responsible for it.

Further, the LTFRB chief strongly denied the “non-appearance” hearing, saying it is “impossible” because such hearings are public and lawyers, applicants, or their duly authorized representatives are required to attend.

“If it is indeed true, I will fire that person collecting (money)….If there is someone who could pinpoint an employee or official and can sign an affidavit and support that affidavit, I will suspend that official,” Ginez said. – Rappler.com

READ: Part 2/Conclusion: Corruption at the LTO

If you have tips and inside information to share, email us at investigative@rappler.com.

*The real names of interviewees have been withheld for their own protection. This story was the author’s final project submitted last March 2015 for her post-graduate Investigative Journalism class at the Ateneo De Manila University.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.