SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

- Narratives pushed out by the propaganda network focus on the creation of an environment that enables – and justifies – violence by branding activists as “terrorists” and exaggerating the communist threat.

- A mix of old and new bloggers, as well as “alternative” news sources, spread these narratives through different clusters that push out content either to the general public or to niche but highly-engaged communities, which then become vectors for distribution. They drown out the real stories of activists being harassed, attacked, and killed.

- The National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), established by the Duterte administration in December 2018, is at the center of the network of Facebook pages and groups pushing out red-tagging content.

- Parallel to online attacks against personalities and progressive groups are the killings of activists – those who do groundwork in mass organizations. Taking from the tokhang playbook in Duterte’s drug war, some police operations against grassroots organizers and local activist leaders resulted in “nanlaban” deaths.

- Organizations with top mentions in the scan include leftist groups such as BAYAN MUNA, Makabayan, Gabriela, League of Filipino Students, and Karapatan. There were also significant mentions of state universities like the University of the Philippines and the Polytechnic University of the Philippines, which state authorities accuse of being “recruitment grounds” for rebels, and a nest for activists-turned-terrorists.

Zara Alvarez served as a human rights defender and paralegal in the Negros islands for Karapatan for more than a decade. She worked tirelessly despite threats and intimidation in a province that’s been witness to decades of war between state forces and insurgents.

Alvarez would see her face on posters linking her to the communist underground and she was, in fact, imprisoned for two years.

Nothing prepared her for the bloody Duterte years. In 2018, Alvarez was one of 600 activists tagged as terrorists by the Department of Justice. What followed was persistent red-tagging and harassment – she got attacked online and was constantly followed while she worked.

Two years later, in August 2020, while walking in the streets of Bacolod City, unidentified men shot Alvarez dead. She was 39.

The story of Alvarez illustrates the direct connection between information operations online and physical attacks, a rehash of the government’s war on drugs where supposed drug users and dealers are demonized online to justify attacks against them in the real world.

Rappler’s research team found out that from drug war narratives, the focus of government’s coordinated online propaganda network has shifted to red-tagging, which lumps activists with terrorists and turns the communist insurgency into a problem that’s bigger than what it really is.

Friends turn into bitter foes

President Rodrigo Duterte himself has enabled this through his speeches and policies.

It’s worth noting that prior to the government’s attacks on the Left, Duterte was friends with them for decades – since he was mayor of Davao. The national democratic movement backed his presidential bid in 2016, and after his election,

Duterte appointed prominent leftist leaders to his Cabinet. He reopened peace negotiations with the National Democratic Front and declared the longest ceasefire with communist insurgents in three decades.

But the talks eventually broke down, as the military gained ascendancy in the Duterte government. By the end of 2017, Duterte’s administration sought to tag more than 600 activists and members of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) as “terrorists.”

The list included alleged CPP chairman Benito Tiamzon, Anakpawis chairman Randall Echanis (who would be killed in his home in 2020), ex-Bayan Muna representative Satur Ocampo, and hundreds of John Does. (READ: “The end of the affair? Duterte’s romance with the Reds”)

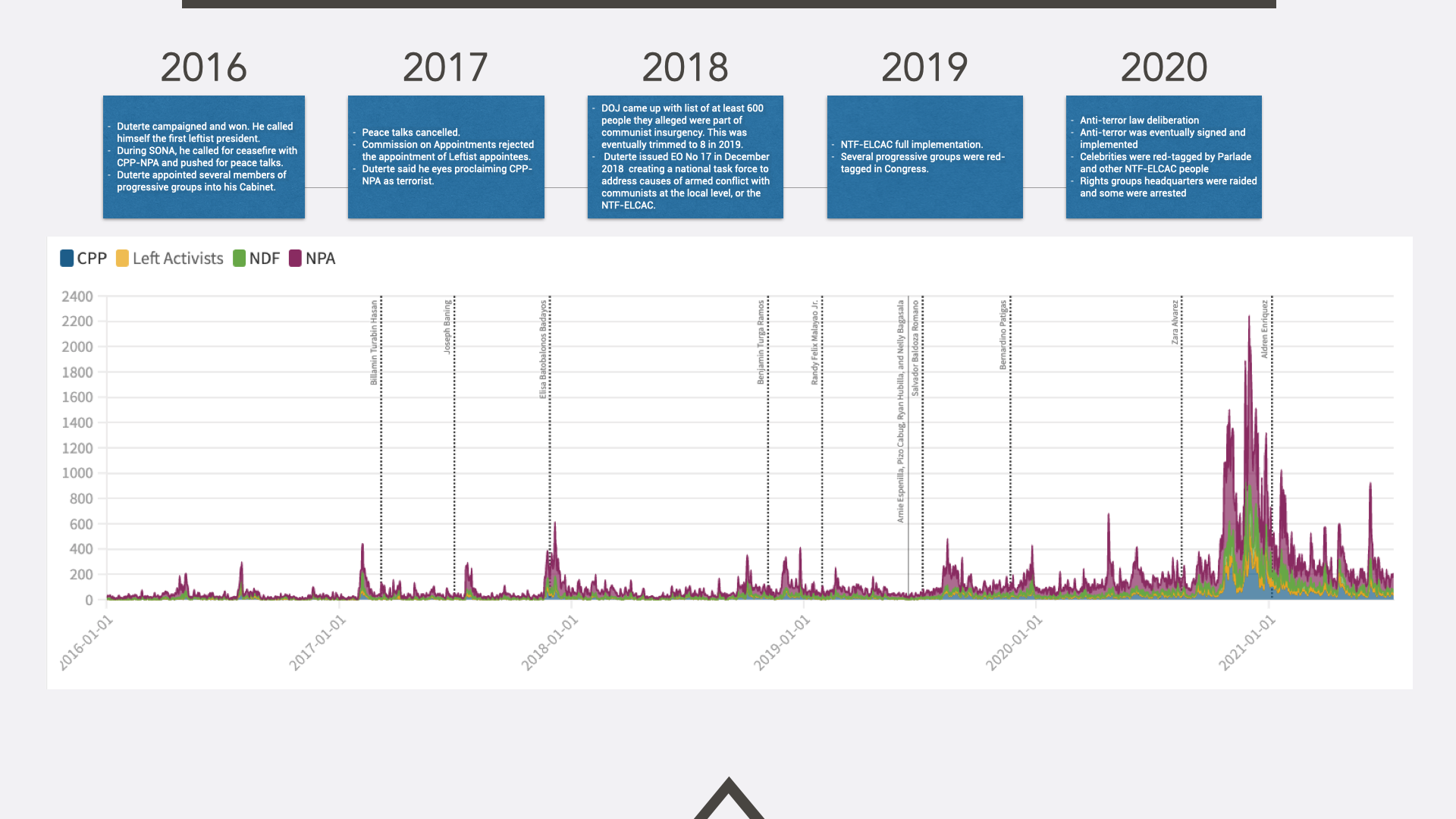

To track red-tagging narratives online from January 2016 to August 2021, Rappler used an initial dataset of posts attacking progressive groups and activists on Facebook, plotted an initial roster of red-tagging entities, and used natural language processing to identify keywords commonly associated with the term. These include keywords like “NPA,” “Left Activists,” and “CPP.”

The graph above shows a timeline of posts with mentions of keywords typically used for red-tagging from 2016 to 2020. While there have been posts in 2016 and 2017 about the insurgency and military propaganda against the Left, information operations intensified in 2018, when it became clear that the Duterte government was abandoning a negotiated settlement of the insurgency and implementing a militarist approach to crush the guerrillas and their supposed front organizations.

In November 2018, for instance, Duterte signed Memorandum 32 that deployed more soldiers and cops in the Negros islands, Samar, and Bicol – known insurgency hotbeds. That same month, Alvarez and the rest of Karapatan-Negros lost a colleague with the murder of human rights lawyer Benjamin Ramos in Kabankalan City. Ramos would be among the first of many Karapatan members and lawyers who would be murdered under the Duterte administration.

The following month, in December 2018, the Duterte administration issued an executive order creating a national task force to address the causes of armed conflict with communists at the local level. This task force came to be known as the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), the main counter-insurgency vehicle that brings together all government agencies for one goal: crush the communists by the time Duterte ends his term in June 2022.

“Doon nagsimula ang malalagim na araw namin (That was when our bloodiest days started),” Clarizza Singson of Karapatan-Negros said as she recounted the incidents between the Sagay massacre in October to the police operations in Guihulngan City in December 2018. Singson had worked with Alvarez for almost a decade before the latter was killed in 2020.

These attacks, particularly against Karapatan members, come not as a surprise, considering that the Duterte government and the Philippine military believe that human rights groups are front organizations of the armed movement.

As Rappler’s scan showed, the government’s campaign against insurgents was complemented by increased activity online. The biggest surge in red-tagging posts was observed in 2020, as the government deliberated on, and eventually adopted, the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 or the Anti-Terror Law.

Shaping the online narrative

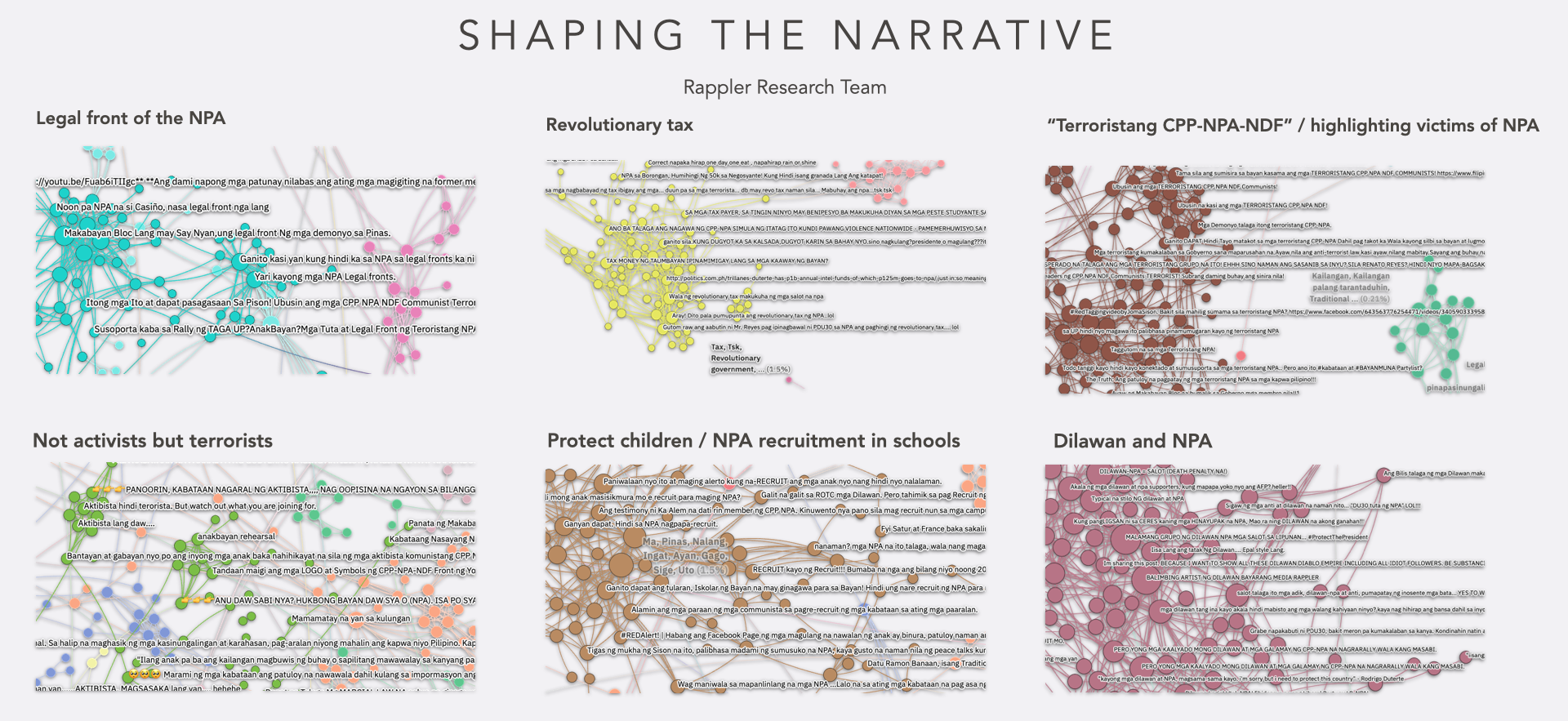

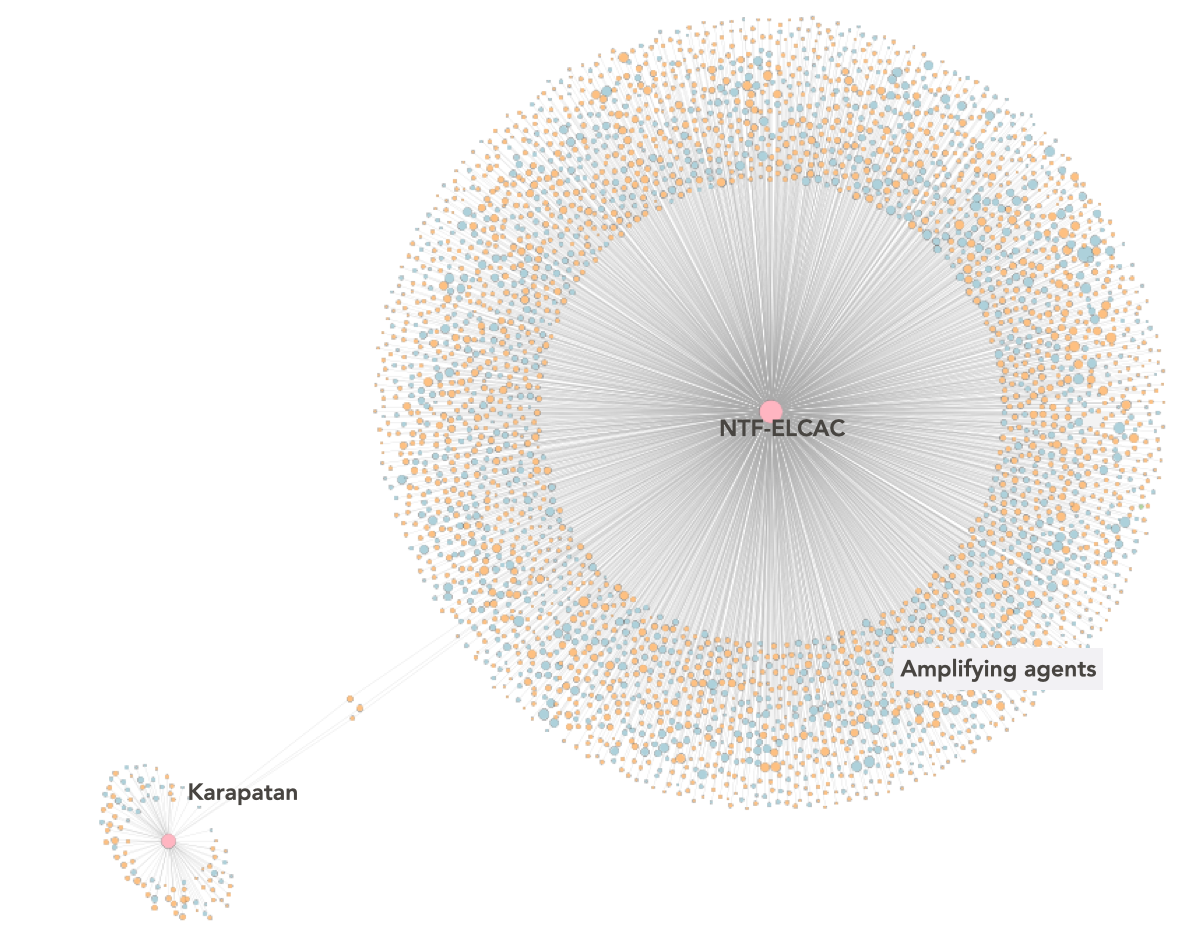

The network map above shows Facebook pages and groups amplifying content related to red-tagging and activism. Pages and groups cluster together when they share content from the same sources. The cluster in blue is the main cluster – mainly pushing out harmful red-tagging content and anti-activist propaganda. Note how the clusters became denser starting in 2018, caused by the increased connectedness of the nodes, showing increased networked behavior.

Using natural language processing, we looked at the general themes pushed out by the main red-tagging cluster.

The narratives pushed out by the main red-tagging cluster show a focus on creating an enabling environment for violence where activists are painted as “terrorists” and the communist insurgency is a problem bigger than what it is. The tactic is reminiscent of the propaganda playbook for the Duterte administration’s brutal war on drugs and how it justified the killings of alleged drug pushers. (READ: [OPINION] First they came for the pushers and addicts. Now, the Leftists)

While the scan also spotted the usual news reports on civilian-military operations, the bulk of the posts used hateful and harmful language targeting activists and progressive groups. These groups were also frequently tagged as legal fronts of the communist New People’s Army (NPA).

Even following her death, Alvarez was not spared from false claims that tagged her as part of the armed movement. Some posts even claimed that the NPA killed her so they could put the “blame [on] the government.” This claim was even echoed by NTF-ELCAC’s former spokesperson Antonio Parlade when he said in a statement, posted on NTF-ELCAC’s official Facebook page, that Alvarez “joined the NPA for two years until 2015.”

Previous investigations by Rappler show similar demonizing language from dubious, anonymously-managed pages known for perpetuating lies and for red-tagging individuals and groups, amplified by police pages and accounts. (READ: With anti-terror law, police-sponsored hate and disinformation even more dangerous)

Targets: Organizations, big personalities

Organizations with top mentions in the scan include progressive groups like Bayan Muna, Makabayan, Gabriela, League of Filipino Students (LFS), and Karapatan. There were also significant mentions of state universities like the University of the Philippines (UP) and the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP), which are accused of being “recruitment grounds” for rebels, and a nest for activists-turned-terrorists. On the other hand, groups like the Liberal Party and the CBCP tend to be accused of defending and coddling “terrorists.”

Threats and red-tagging often target big progressive voices in Congress, like Kabataan Partylist Representative Sarah Elago and Bayan Muna Representative Carlos Zarate. Akbayan Senator Risa Hontiveros was also often called out for her alleged silence on crimes committed by the NPA.

High-profile activists like former Bayan Muna representative Teddy Casiño, as well as celebrity-turned-activist Angel Locsin, were also often targeted and linked to the NPAs. No less than Parlade himself alleged that Locsin’s sister is an NPA – a claim Locsin has consistently denied.

And aside from military and NTF-ELCAC spokespersons, the propaganda network would quote “ex-rebels” in their propaganda and red-tagging. These “ex-rebels” are often used to “expose” how rebel recruitment is done in schools, and to supposedly unmask activists who are allegedly members of the armed rebellion.

Hiding like criminals

While all these are happening online, activists who are not as popular as the targets of the online information operations are being killed on the ground.

Taking from the same tokhang playbook, some police operations that targeted grassroots organizers and local leaders of progressive groups resulted in “nanlaban” deaths. This included the “bloody Sunday” operations in Calabarzon in March 2021 that left nine activists dead.

“Sanay na kami sa death threat kasi minsan three times a day. Minsan once a week. Minsan once a month…Pero syempre hindi ‘yun empty threats. Pinapatay at namamatay mga kasama ko,” Singson said. (We are used to death threats. Sometimes, we get it three times a day. Sometimes, once a week or once a month. But these threats are not empty threats. My colleagues are being killed and have been killed.)

According to her, they were subjected to surveillance, trumped-up cases, arrests, raids, direct threats, and other forms of harassment. Since Duterte became president in 2016, at least 16 Karapatan members have been killed.

They have adjusted by strengthening their security protocols and learning how surveillance works. They employed a buddy system, changed their schedules, and avoided going outside their homes during the day. In Singson’s case, they went as far as abandoning their home and uprooting her whole family – her two young sons included – to live in rented apartments.

The slain Alvarez experienced close surveillance. According to Singson, unidentified individuals would openly follow and take photos of her even in public spaces.

The necessary adjustments and new security measures disrupted their lives. The tactic of using the drug war playbook against activists seemed to have worked as well. Singson said the way they hid and protected themselves felt like they were being hunted as criminals.

“Yung mga bata ayaw namin isubject sa ganung buhay na nanonormalize ang fear, terror, at killings… Para kaming wanted criminal. Daig pa namin ang wanted criminal,” Singson added. (We don’t want to subject the kids to that kind of life where fear, terror, and killings are normalized. We were like wanted criminals.)

When Alvarez was gunned down, Singson and her other colleagues in the province received messages from anonymous perpetrators: “You’re next.”

Singson fought back against the kind of attacks they experienced. She filed a case at the cybercrime division of the National Bureau of Investigation to track those who, on her Facebook account, threatened to have her head severed. She took screenshots and printed out all the hate messages and death threats she received.

But nothing came out of it. According to her, the cybercrime division concluded that the accounts used to attack her were hacked and that was the end of the story.

Sophisticated information operations

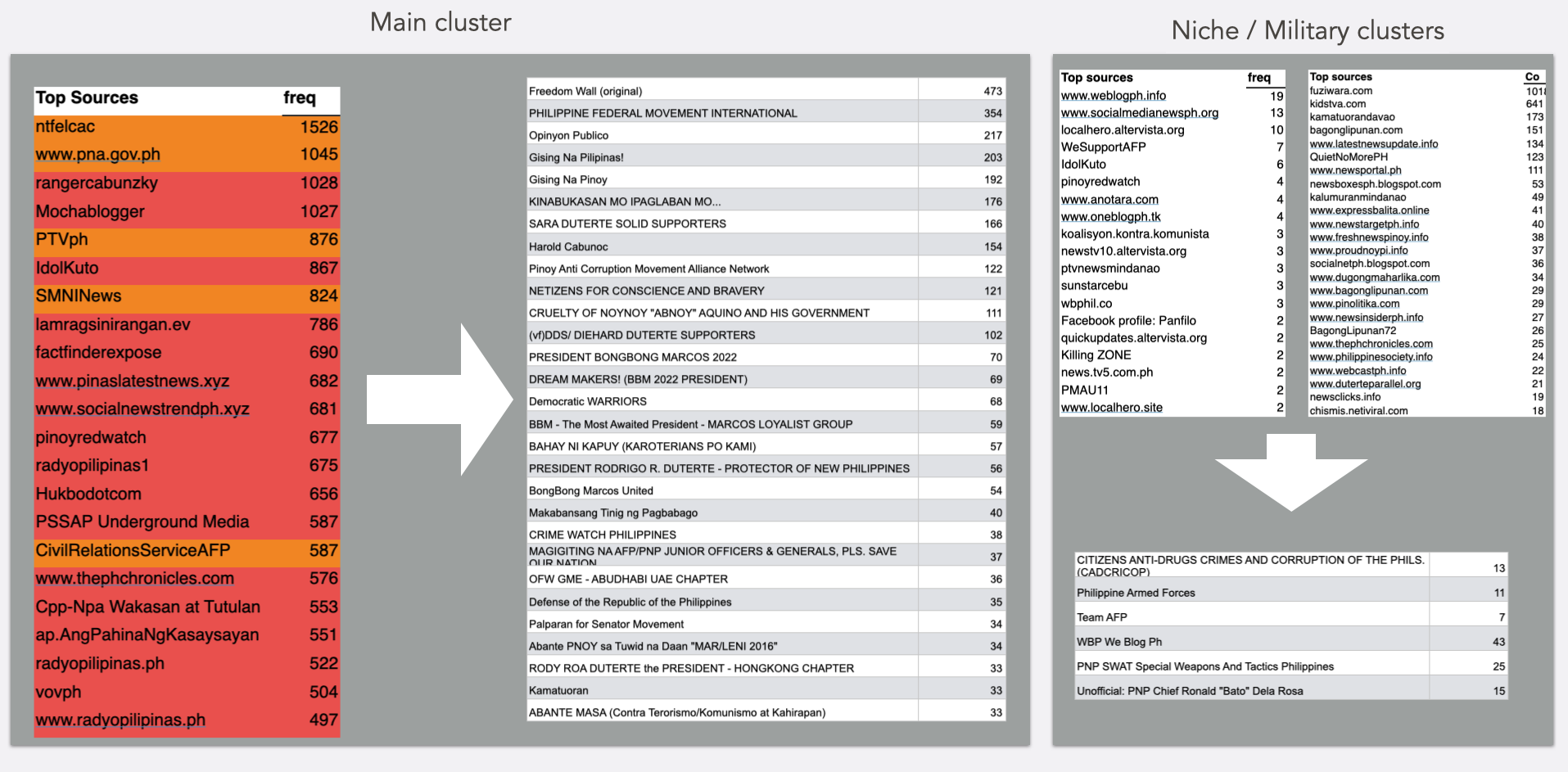

Rappler’s network analysis showed that the online narratives are seeded through a mix of old and new bloggers and “alternative” news sources, with different clusters focused on either funneling to the general public (through hyperlocal and political pages), or niche but engaged communities (e.g., military, police, and their supporters), which become vectors for distribution.

At the center of the campaign is the official Facebook page of NTF-ELCAC. Content from other state media like the Philippine News Agency and PTV is also often pushed to spread red-tagging narratives. Previous Rappler investigation has documented how official government platforms, including the hugely-funded NTF-ELCAC, were being used to attack and red-tag local media. (READ: Gov’t platforms being used to attack, red-tag media)

SMNI News, the broadcasting arm of Filipino televangelist and pro-Duterte church leader Pastor Apollo C. Quiboloy, has also been an active source of news content related to the communist rebellion, often shared by the red-tagging cluster.

Official military channels are also among top content creators amplified by the cluster, such as the official Civil Relations Service Armed Forces of the Philippines.

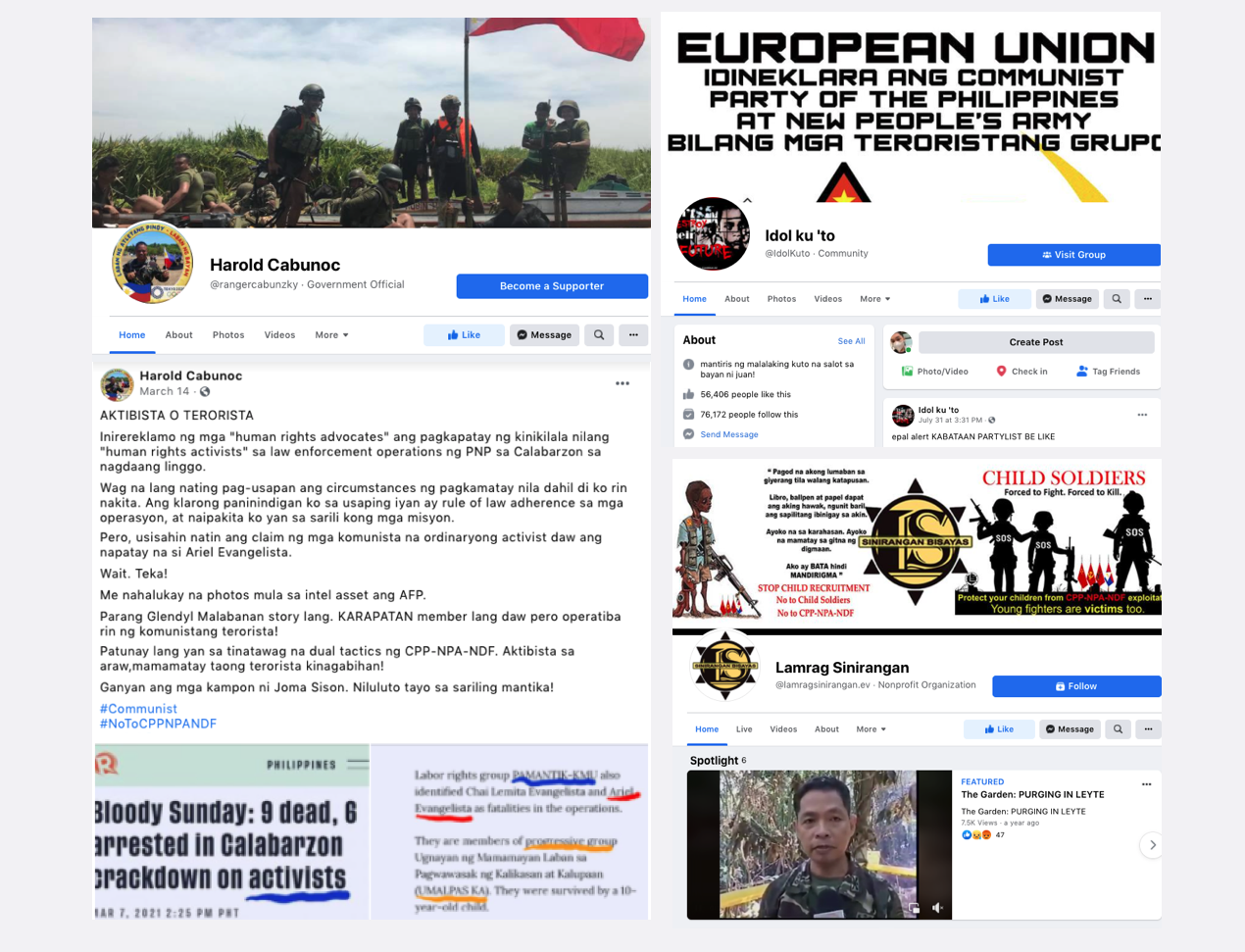

Army officer Colonel Harold Cabunoc’s Facebook page is also among the most active in creating military and anti-insurgency propaganda. The colonel has also had a history of red-tagging online, and has also been red-tagging slain activists.

Other pages shown to be actively pushing out military propaganda are IDOL KU ‘TO, LAMRAG SINIRANGAN, and Pinoy Red Watch.

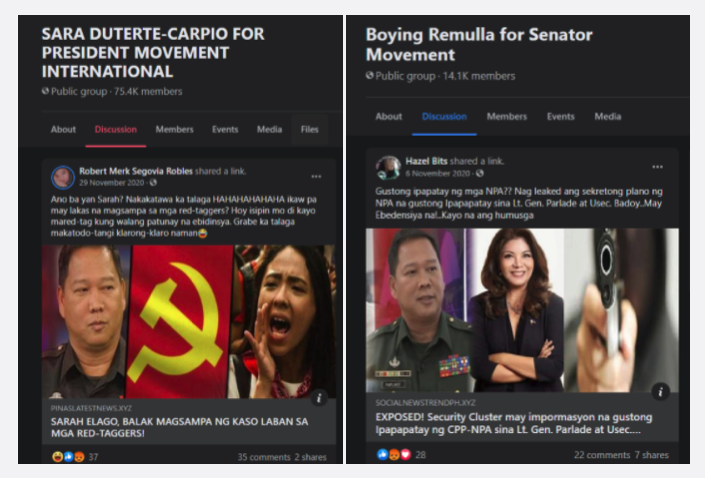

“Alternative” news sources were also actively being funneled by the cluster, including websites pinaslatestnews.xyz, and socialnewstrendph.xqz. These websites post “news” content related to communists, and “report” about government propaganda against activists and progressive groups.

Other pages often amplified by the main cluster include known propaganda pages Mocha Uson Blog and VovPH.

Content from these sources is shared in hundreds of Facebook pages and groups, mostly political but also including community and interest hubs, with captions that actively call out activists as terrorists, and highlight the narratives identified above.

While the main cluster effectively distributes these content to the general public, other clusters showed similar content, also mostly coming from “alternative” news websites and “news aggregators” that are funneled into Facebook groups with special interest in military and anti-insurgency activities, such as Team AFP, Philippine Armed Forces, and the “CITIZENS ANTI-DRUGS CRIMES AND CORRUPTION OF THE PHILS.”

Public support amid culture of terror

While the online and on-the-ground attacks were public and blatant, support for human rights and progressive groups was muted online.

Karapatan secretary-general Cristina Palabay claimed their network and community continuously expanded since 2018 when the attacks against them and other progressive groups increased. “Sa international, after the NTF-ELCAC, dumami rin ang kaibigan namin,” Palabay said. (In the international scene, after the creation of NTF-ELCAC, we gained a lot of supporters.)

But this widespread support and network group has yet to translate online. In the digital space, their stories are often told exclusively by select media and the network of progressive groups and human rights activists.

The network map above shows the network of pages and groups that amplified content with mentions of 16 Karapatan members killed during the Duterte administration. While progressive groups have their own network of pages and distribution channels, as seen above, they are small in comparison to the red-tagging and propaganda network.

In the visualization below, we compare the amplifying agents (Facebook pages and groups sharing their content) of NTF-ELCAC and progressive group Karapatan, as captured by Rappler’s SharkTank in 2020. The two entities were chosen because they were the most distributed content sources for government propaganda and in conversations on activists killed.

The scan showed a huge difference in the size of the networks that amplify both channels – painting a picture of an environment where stories of slain activists like Alvarez remain within the echo chambers of other activists online and are effectively drowned out by government propaganda that blurs the lines between activism and terrorism.

What makes this enabling online environment more dangerous is how it reinforces the lack of public accountability for the harassment and killings of human rights workers, lawyers, and activists.

It also further weakens mechanisms that are supposed to protect individuals who are already vulnerable to attacks such as Alvarez, who asked the Supreme Court for protective writs because she was being harassed.

She died before the court came up with a decision on her appeal. – Rappler.com

Data visualizations by Akira Medina, Dylan Salcedo

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] ‘Some people need killing’](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/tl-some-people-need-killing-04172024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

![[Judgment Call] Resisting mob mentality for warrantless arrests](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/judgement-call-mob-mentality.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=352px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.