SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – The concept may be problematic in the Philippines but human rights are a vital component of most modern democracies.

Human rights allow a person to live with dignity and in peace, away from the abuses that can be inflicted by abusive institutions or individuals. But the fact remains that there are rampant human rights violations around the world.

To further promote the importance of human rights in the Philippines, December 4 to 10 of each year is marked as National Human Rights Consciousness Week via Republic Act No. 9201.

December 10 is also considered as the United Nations Human Rights Day. It commemorates the day the UN General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948.

But do we really know our human rights? Rappler answers some key questions:

1. What are human rights?

Human rights, according to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, refers to norms that aim to protect people from political, legal, and social abuses.

The United Nations (UN) defines human rights as universal and inalienable, interdependent and indivisible, and equal and non-discriminatory.

- Universal and inalienable:

Human rights belong to all and cannot be taken away unless specific situations call for it. However, the deprivation of a person’s right is subject to due process. - Interdependent and indivisible:

Whatever happens to even one right – fulfillment or violation – can directly affect the others. - Equal and non-discriminatory:

Human rights protect all people regardless of race, nationality, gender, religion, and political leaning, among others. They should be respected without prejudice.

Human rights can also be classified under individual, collective, civil, political, economic and social, and cultural.

2. What laws or legal documents ensure the human rights of Filipino citizens?

The rights of Filipinos can be found in Article III of the 1987 Philippine Constitution. Also called the Bill of Rights, it includes 22 sections which declare a Filipino citizen’s rights and privileges that the Constitution has to protect, no matter what.

Aside from various local laws, human rights in the Philippines are also guided by the UN’s International Bill of Human Rights – a consolidation of 3 legal documents including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

As one of the signatories of these legal documents, the Philippines is obliged to recognize and apply appropriate laws to ensure each right’s fulfillment.

This is not always the case, however, as the Philippine Constitution lacks explicit laws to further cement specific human rights in the local context.

For example, the Right to Adequate Food may be included in the UNDR but it is not explicitly indicated in the Philippine Constitution. Thus the government cannot be held responsible if this is not attained. (READ: Zero Hunger: Holding gov’t accountable)

3. Who oversees the fulfillment and protection of human rights in the Philippines?

Human rights are both rights and obligations, according to the UN. The state – or the government – is obliged to “respect, protect, and fulfill” these rights.

Respect begets commitment from state that no law should be made to interfere or curtail the fulfillment of the stated human rights. Protecting means that human rights violations should be prevented and if they exist, immediate action should be made.

In the Philippines, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) primarily handles the investigations of human rights violations. However, it has no power to resolve issues as stated in the Supreme Court decision in 1991.

Established in 1986 during the administration of President Corazon Aquino, CHR is an independent body which ensures the protection of human rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights.

Aside from investigations, it also provides assistance and legal measures for the protection of human rights guided by Section 18 Article XIII of the Philippine Constitution.

4. Do criminals or those who break the law still enjoy human rights?

Criminals or those in conflict with the law are still protected by rights as indicated in many legal documents such as the Philippines’ Criminal Code and UN’s Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners.

Specific human rights, however, may be removed, provided they go through due process beforehand.

In 2002, the CHR issued an advisory after the debate sparked by Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte’s statement during a crime summit in Manila. He said extra-judicial or summary killings remain “the most effective way to crush kidnapping and illicit drugs.”

However, according to the CHR, summary or extra-judicial executions of criminals or suspects are prohibited under the Philippine Constitution as these violate several sections such as Article III Section 1, which states that “no person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law nor shall any person be denied the equal protection of the laws.”

It added that summary executions as a violation of human rights are more explicit in Article II of Section 11, which provides that “the State values the dignity of every human person and guarantees full respect for human rights.”

Meanwhile, Section 19 of the Bill of Rights clearly states that any punishment against a prisoner or detainee shall be dealt with by law and through due process. It also says that no “cruel, degrading or inhuman punishment” may be inflicted – even death.

5. How does the Philippines fare when it comes to human rights violations?

In a Rappler piece, Human Rights Watch (HRW)’s Asian Division researcher Carlos H. Conde wrote that President Benigno Aquino III had more “rhetoric than concrete action” despite his “explicit human rights commitments” in 2010.

Human rights violations – extrajudicial killings, torture, enforced disappearances, and human trafficking, among others – may have decreased in the past years but cases still exist and remain unsolved, according to Human Rights Watch.

In its 2015 World Report, the international group lauded the efforts to resolve these violations. These include the arrest of retired army general Jovito Palparan in relation to the disappearance and torture of two University of the Philippines students in 2006, and the peace agreement between the government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, among others.

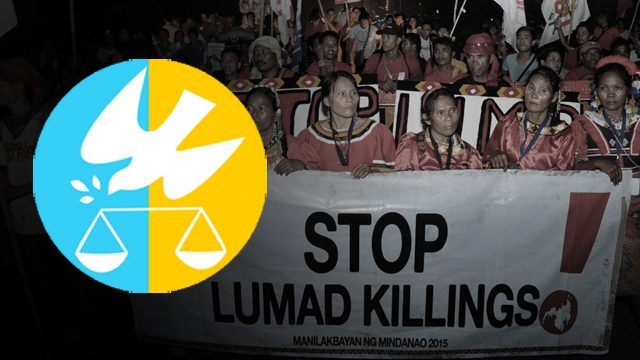

The recent issue over the killings and displacement of Lumads, however, has put the government’s way of handling human rights issues under the spotlight. (READ: A rare time a human rights issue captivates PH social media)

Meanwhile, nearly 75,000 people filed for recognition as victims of human rights violations during the administration of President Ferdinand Marcos in 2014. Martial Law is regarded as the “dark years from 1972-1986 due to a huge record of abduction and torture, among others, under the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos.” (READ: A Marcos brand of amnesia) – Rappler.com

Handprints photo from Shutterstock.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.