SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Data is the new oil, as they say. It seems everyone wants a piece of it. Hackers. Social networks. Internet giants. Device makers. Cloud service providers. Heck, even fitness apps. And now you can add a new one to the list: governments.

The world’s states themselves want to look at your data – what you’re saying, what people are saying to you, what you’re thinking, sentiments, stuff you may want to keep for yourself. It’s your right to keep some things private, free from the interference of governments or other actors, and free from the fear of being spied on.

It’s a freedom that’s hanging in a balance, according to a new report by United Nations (UN) special rapporteur on freedom of expression, David Kaye.

Kaye updated a 2015 report that found encryption and anonymity were important ingredients in maintaining society’s ability to be able to formulate opinions and express them in the digital age.

The two elements form what Kaye calls “a zone of privacy” that protects opinion and belief. This zone of privacy enables private communications and shields opinion from outside scrutiny, a condition that is “particularly important in hostile political, social, religious and legal environments.

In places where government censorship reigns or downright attacks dissenters, encryption and anonymity are said to be empowering tools that allow information access and communications without government intrusion, control, influence and pressure.

The original report called for the protection of these elements as it would be tantamount to protecting the human right to free expression itself.

The UN’s calls went unheeded in the 3 years since the report, however. In the updated 2018 report, digital protection of encryption and anonymity only worsened, with Kaye observing a surge in state restrictions on encryption. “The 2015 Report noted ways in which States interfere – or were then proposing to interfere – with encryption.

Since then, “state practice has not improved and may have become less protective of digital security,” Kaye wrote. The challenges users face have “increased substantially,” noted Kaye, with states often seeing “personal, digital security as antithetical to law enforcement, intelligence, and even goals of social or political control.”

A few exceptions from the trend towards state surveillance and encroachment of personal privacy: The Netherlands’ public recognition of encryption and its stance on not enacting laws that may threaten it, and the implementation of the European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Kaye provided key examples of how a considerable number of states have moved against encryption and anonymity. Here’s the list:

1) Pakistan’s 2016 Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, which could be used to crack down on encryption tools and networks that provide anonymity like virtual private networks (VPN) and the anonymous communication software, Tor.

2) Iran’s Computer Crimes Act, which bans encryption.

3) Turkey arrested thousands of citizens who allegedly used an encrypted messaging app, linked to a July 2016 coup attempt by the opposition.

4) Vietnam’s 2015 Law on Network Information Security; Malawi’s 2016 Electronic Transactions and Cyber Security Act; and Russia’s 2016 “Yarovaya Law” all have provisions that require government approval for the use of encryption tools. These laws are said to reverse the state’s role in preserving the right to expression.

Government approval requirements may also raise the prospect that approval may entail government intrusions through backdoors or vulnerabilities, says the report.

5) In general, there is a mounting trend of states pressuring companies to install “backdoors,” which are intentional security vulnerabilities through which law enforcement can “come in” and access encrypted communications or open secured devices.

6) The United Kingdom’s (UK) 2016 Investigatory Powers Act, which may provide authorities a way to compel network operators, social networks, webmail hosts, and cloud service providers to build “backdoors,” remove encryption, and cooperate with government hacking. Other states have looked at the UK law as a model for their own encryption-threatening laws.

7) Australia announced its intention to introduce laws that would “impose an obligation upon device manufacturers and…service providers” to assist government authorities to cooperate and provide assistance during certain cybersecurity-related instances.

8) China’s 2016 Cybersecurity Law requires network operators to also “provide technical support and assistance” when the government requires it for the purposes of national security and law enforcement.

9) In 2015, the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) compelled Apple to create software that would unlock the iPhone of a suspect in a California shooting that claimed 14 victims. Apple stood firm and said no. The FBI eventually got the phone’s data with the help of a third party.

The incident “highlighted how security vulnerabilities introduced on a single device and for a specific investigation could nevertheless be exploited to compromise all devices of the same model or type,” said the report.

10) Not unlike a traditional hacker, governments themselves have employed hacking for surveillance, data manipulation, and to launch denial-of-service attacks to force the shutdown of websites or services to name a few uses. Uganda’s military and law enforcement reportedly used malware to collect information on politicians they don’t agree with, with the aim of being a step ahead and crushing them.

11) Like Uganda, some authorities in Mexico reportedly use malware to track civilians including journalists, lawyers, anti-corruption activists, lawyers, and consumer advocates.

12) In the UK, Italy, and the US, there are a number of laws that are feared to be vague enough to allow the government to hack into computers and search electronic media legally.

13) In China, Russia, Kazakhstan, and the US, laws have been enacted that force companies to keep data stored in local data centers, keep encryptions keys within the country, or hand over the encryption keys to the government for storage.

One high-profile company who had to follow local rules was Apple, which announced plans in February 2018 to store encryption keys for Chinese iCloud accounts within China. Apple also removed VPN services from its China App Store after China passed VPN restriction laws.

14) In South Korea, authorities can access customer identity data held by telcos without a warrant.

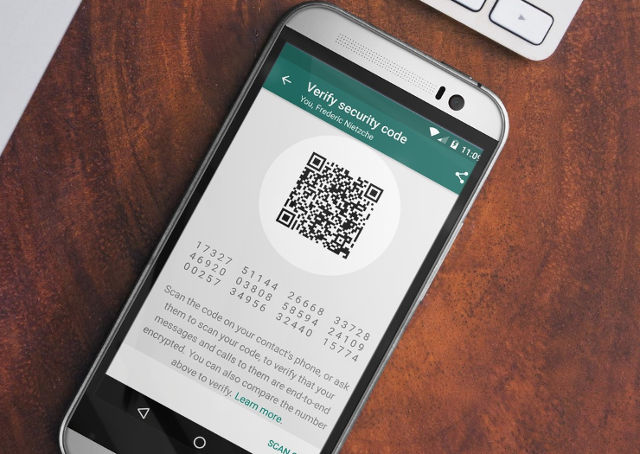

On the other hand, Kaye’s report has noted that while governments have continued their crackdown on encryption and anonymity, private companies such as device makers and messaging app developers have been diligent in improving their security features such as end-to-end encryption and built-in encryption tools and lock/unlocking mechanisms.

The report is less rosy for internet service providers, which notes instances that threaten encryption. “Although there is little or no information about whether companies in fact collect and analyze data about encrypted network traffic, researchers have previously discovered attempts by ISPs in the United States and Thailand to tamper with e-mail encryption,” said the report.

It also notes that in spite of vows of data privacy, the world’s most high-profile service providers including Vodafone and AT&T have remained vague about how they handle encrypted data.

All these types of private companies would do well to stay vigilant and continue evaluate their responsibility to protect encryption and anonymity, said the report.

As for states, the report reiterated its message from the original 2015 report: “States should adopt laws and policies that provide comprehensive protection for and support the use of encryption tools, including encryption tools designed to protect anonymity. Legislation protecting human rights defenders, journalists, artists, academics and civil society should also be enacted and include support for the use of such tools.”

The full report appears below.

– Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.