SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

On the afternoon of June 7th last summer, officers from the Columbus Division of Police arrived at Heyl Avenue on the Ohio capitol’s east side after being alerted to gunfire. After hearing what he also thought were gunshots, Jonathan Robinson, a 25-year-old black man who lived in the neighborhood with his wife and two young children, decided to retreat to his home.

When police arrived, they demanded that the family exit their home in order for them to investigate.

Seeing an officer speaking aggressively with his wife outside, Robinson stepped in to defend her. Officer Anthony Johnson — known locally as the “dancing cop,” following a viral video of him dancing with local children — was holding a shotgun. When Robinson approached, Johnson, who is mixed race, pushed him, then punched him in the neck. Robinson was arrested and charged with obstruction of police business and disorderly conduct. He was released after one day.

The incident was captured on video by an onlooker and uploaded online. To date, it has been viewed over 180,000 times. The southside of Columbus, which is majority black and working class has a history of tense relations with local police. The Comprehensive Neighborhood Safety Strategy was launched in 2017 by Columbus Mayor Ginther’s administration, and includes increased the use of bicycle and foot patrols, and technology to combat gun violence, drug dealing, and homicide.

Robinson says, “We are a close-knit family here and we protect the neighborhood in numerous ways. We clean up the neighborhood a few times a month. These officers came into the community like troops entering an Iraqi community.”

Upon his release, Robinson filed a civil complaint against CDP for using mace in the presence of his children. The video led to community protests outside Johnson’s home and charges that CPD had filed against Robinson were dropped.

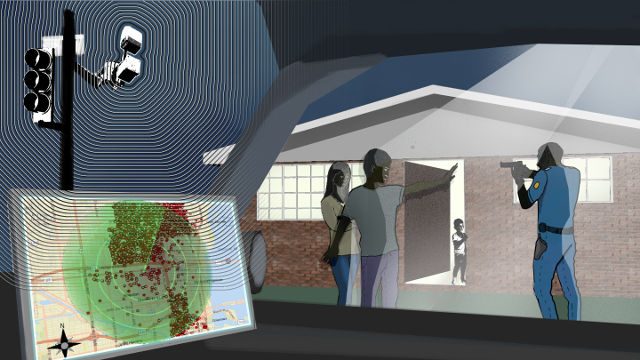

The reason CDP officers raced to Heyl Avenue was because they had received a report of gunfire in Robinson’s neighborhood from ShotSpotter, a gunshot detection technology. Launched in 1996 by SST Inc, headquartered in Newark, California, ShotSpotter has been installed in over 100 cities in the U.S., including Chicago and Las Vegas.

Across the nation, residents in cities like San Diego, Durham, and beyond have noted the consistency of the technology being installed predominantly in communities of color. The three neighborhoods where ShotSpotter is already installed in Columbus (Hilltop, Linden, and the South Side) are some of the city’s most economically vulnerable areas.

According to its website, ShotSpotter “uses sophisticated acoustic sensors to detect, locate and alert law enforcement agencies and security personnel about illegal gunfire incidents in real-time.”

ShotSpotter is set up by installing multiple sound-monitoring microphones in a predetermined area. These detect gunfire based on the company’s algorithm. If ShotSpotter picks up audio that sounds like gunfire, a recording is sent to a 24-hour monitoring center in Newark, California, where it’s reviewed by experts. The results are then transmitted to local police officers. According to the company, the process can take as little as 30 seconds, as opposed to the average three-to-five minutes for any first call to 911 once a shot is fired.

Shotspotter’s website points to research which says that it has led to increased response time to gunshots, better gathering of evidence like bullet casings, and an improvement in police-community relations.

Lethal force in Ohio

Although violent crime has steadily decreased in the U.S. over the past two decades, the dangers of mass shootings and gun crime are increasingly apparent. In response, police departments nationwide have become more militarized, making technologies like ShotSpotter a tempting proposition.

Ohio is no exception to gun violence. Earlier last year, nine people were killed during a mass shooting in Dayton. Elsewhere, a six-year-old girl, Lyric Lawson, was killed while sleeping in her home by a stray round from a drive-by in Cleveland. Despite the assumption that police will be the institution to curb gun violence, the reality is complicated for poor, black or brown communities. In 2018, 54% of the CDP’s use of force incidents involved African Americans. A nationwide 2016 Cato study found that 73% of African-Americans believe that police are too quick to use lethal force.

Ohio is notable for a number of high-profile police killings. For example, Tamir Rice (12), Tyre King (13), and John Crawford III (22) are all young, black Ohioans who have been killed in the past five years by police officers for carrying BB guns.

This history of police misconduct in Ohio is longstanding. In 1999, the Justice Department sued the City of Columbus for tolerating patterns of excessive force, false arrest, and illegal searches and seizures. Last year, the CDP disbanded its vice unit in response to internal and FBI investigations carried out after recent charges against Officer Andrew Mitchell, alleging he forced two women to have sex with him under threat of arrest. Officer Mitchell is awaiting trial on these charges, as well as the murder and involuntary manslaughter charges for his August 2018 killing of Donna Castleberry.

In 2014, the Justice Department released a damning review ordering the Cleveland Police Department to improve the department’s practices.

The implementation of ShotSpotter in Columbus coincides with other nationwide initiatives to invest in online technologies, with the aim of making cities safer and more user friendly. The Smart Columbus initiative, was launched in 2014, after the city emerged victorious over 77 others across the U.S. competing in the Smart Cities Challenge. Columbus was awarded a total of $50 million in funding from the U.S. Department of Transportation and the philanthropic enterprise Vulcan Inc.

“The rationale for instituting the technology is that law enforcement all around the country are trying to decrease firearm violence,” said Dr. Daniel Lawrence a senior research associate with the Washington D.C.-based think tank the Urban Institute, in an interview. “They want to be able to better identify where firearm violence is occurring, so they utilize gunshot detection technology in high-crime areas where there is known firearm violence present.”

Effectiveness of Shotspotter

One of the most commonly highlighted weaknesses in ShotSpotter’s technology is the number of false positives — in other words, other environmental noises that are mistakenly categorized as gunfire. The company has claimed that it addressed this issue by hiring employees in 2011. Their job is to check in real time the gunshot alerts received daily at ShotSpotter’s California headquarters. The company says its accuracy seen a substantial improvement as a result. In 2018, ShotSpotter said it had detected 107,000 gunshot incidents across the U.S.

A 2013 investigation of the effectiveness of ShotSpotter in Newark, New Jersey revealed that from 2010 to 2013, the system’s sensors alerted police 3,632 times, but only led to 17 actual arrests. According to the investigation, 75% of the gunshot alerts were false alarms.

Representatives at ShotSpotter declined to be interviewed for this story. However, the company claims that it has addressed this issue, but cases like that of Robinson in Columbus where ShotSpotter mistook fireworks for gunfire, according to one community account, prove that false positives can lead to problems that ShotSpotter and police haven’t addressed.

A 2016 report by the Center for Investigative Reporting analyzed ShotSpotter’s usage in San Francisco from 2013 to 2015. It found that the technology sent police to the wrong location for gunshot alerts 20% of the time, that two-thirds of alerts led to no evidence of shootings, and that only one gun-related arrest could be attributed to it.

For communities in Ohio and beyond that have installed ShotSpotter, procedural justice is an important concern — especially when police departments have a history of poor training, using excessive force or racial profiling.

The case of Silvon Simmons in Rochester, New York underscores concerns over ShotSpotter’s operational biases. On the evening of April 1, 2016, Simmons was exiting his friend’s Chevrolet Impala, the same model of car that belonged to a man suspected of threatening a woman with a firearm. A flashlight beam pointed his way and obstructed his vision. All he could make out was a white man approaching him with a gun drawn.

Simmons was accused of firing the first shot and charged with the attempted murder of a police officer, among other offences. Recordings by ShotSpotter were used against Simmons at trial, but evidence surfaced that the service had initially categorized loud noises in his neighborhood as the sound of a helicopter overhead — until Rochester police notified the service that an officer-involved shooting had taken place. ShotSpotter would then change the number of gunshots that it had reportedly detected from three shots to four shots, and then five shots.

After spending 18 months in jail and eventually being cleared of attempted aggravated murder, aggravated assault of a police officer, and two counts of criminal possession of a weapon in the second degree, Simmons is now suing the city of Rochester, two police officers, a former police chief, and ShotSpotter. Matters were complicated when Paul Greene, the Forensic Services Manager of ShotSpotter, admitted in court that the audio file from the time of Simmons’ shooting was gone. Greene also admitted that unlocked or unencrypted ShotSpotter audio files can be altered by ShotSpotter employees or police.

Activists’ concerns

Examples of police misconduct, like in the Simmons’ case, and the eagerness of cities to adopt ShotSpotter are compelling communities to push for police accountability boards and community control over police surveillance laws.

Valeria Bai and Rachael Collyer, organizers with the Cleveland branch of the Ohio Student Association (OSA), which advocates for racial, economic, educational, and social justice, warn that technologies like ShotSpotter are not comprehensive solutions to gun violence.

“The temptation to grasp for these false, short-term solutions is really missing the fact there are no quick fixes for this,” said Collyer in an interview. “This issue [of gun crime] is coming out of deep deprivation of resources and lack of access to opportunities that communities have been experiencing for decades and decades.”

Gunshot detection systems, however, are only one part of a larger web of surveillance. For police and cities, general surveillance can range from automatic license plate readers that help the city map traffic, unmanned aerial vehicles like drones, or phone trackers.

OSA Cleveland learned of the city council’s Safety Committee’s plan to decide whether to pursue a two-year contract with an undetermined gunshot detection technology just two days before the vote was due to occur on August 21. The group drafted a letter of opposition to the city council that detailed potential community concerns, ranging from the lack of transparency in the vote that led to the adoption of the technology, allegations of police misconduct and privacy concerns about the detection systems themselves.

In response to concerns over privacy, last year, ShotSpotter initiated a privacy audit with the Policing Project at New York University. The Policing Project found that “the risk of voice surveillance was extremely low.”

This trend of city councils voting on gunshot detection technology without adequate community input is commonplace. Because of this, the responsibility of informing the public of new forms of surveillance often falls to community members and local organizers.

“Everything from our perspective feels rushed and is so one-sided,” said Bai, explaining why 13 cities around the country have passed community oversight on police surveillance laws, which allow residents to decide if and how surveillance technologies are used.

Gunshot technology expands

Ohio’s moves toward increased surveillance do not appear to be slowing down. This year it was revealed that the state had used facial recognition software to analyze drivers’ license photos without the consent of state residents.

ShotSpotter has been implemented in six cities since 2010. Thus far, Canton is the only city in Ohio to discontinue using ShotSpotter. The Canton Police Department explained that their decision to move from ShotSpotter to Wi-Fiber, a different gunshot detection technology, earlier this year was because Wi-Fiber will be owned by the city, cover more square miles, be more mobile, and integrates better with other technologies.

In 2015, ShotSpotter signed a memorandum of understanding with GE Lighting, which is headquartered in Cleveland. According to the document, the agreement “lays ground to embedding sophisticated ShotSpotter technology into GE’s intelligent LED street lights.”

Despite its limitations, gunshot detection technology from the U.S. is also spreading to other countries. Last month, ShotSpotter announced that it had signed a $4.27 million, three year deal with the Puerto Rico Public Housing Authority. ShotSpotter’s technology will be used in three of the country’s cities, including the capital San Juan.

Bai and Collyer of OSA Cleveland say they will continue to educate Clevelanders about gunshot detection technology while potentially pushing for a Community Control Over Police bill, which was created in 2016 by civil liberties organization, for city council and police.

Bai says, “OSA will encourage community involvement at the future Q&A session with city council and the vendor. We will be in attendance and make our voices heard regarding our concerns about shotspotting tech’s threats to Clevelanders’ civil liberties. As part of the Coalition to Stop the Inhumanity at the Cuyahoga County Jail, we will be working to spread the word and educate people about ShotSpotter and to make sure the community is aware of the public Q&A once the specific date is shared with us.”

Until that happens, poor and minority communities will continue to be surveilled by compromised and unreliable technology, leaving them vulnerable to wrongful arrest, detention and far worse.

On whether CPD officers should have acted differently on June 7th, Robinson replied, “Of course they should have. But with hate crimes up against African Americans, are we surprised that law officers wouldn’t act in the same manner? Would you trust a fox guarding a chicken coop?” – Rappler.com

Prince Shakur is a queer, Jamaican American journalist based in Columbus. His writings on queer culture, films, and law enforcement have been featured in Teen Vogue, Catapult Story, The Appeal, and more.

This article has been republished from Coda Story with permission.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.