SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

SAN FRANCISCO, USA – I became a photographer when Ed Gerlock, an ex-Maryknoll priest deported by Marcos, bought my first camera during his speaking tour in Hong Kong.

Since then, without any formal photography, art or photojournalism background, the photo-documentary personal projects that I have done in more 30 years reflects this cherished memory.

My worldview developed during my years as an anti-Marcos activist in the US and my equal involvement in racial and discrimination issues and support for national liberation movements.

The same politics became my guiding light working on projects like “Its About Time,” a project about Japanese-Americans while they wait for reparation for their unjust incarceration in World War II; spending 18 years documenting the life of Filipino WW II veterans while they wait for equity; and 10 years of work documenting Bay Area Muslim-Americans after 9/11, civil liberties issues for ACLU of Northern California, among others.

As we celebrate EDSA this week and recall the many years of struggle against the dictatorship that caused the loss of lives, limbs, and delayed careers, I would like to share some memories during martial rule before and after I started using my camera as a tool to denounce the brutal dictatorship of Marcos.

With press credentials from the Pacific News Service and clearance from the Secret Service, I infiltrated the welcome events organized by local Hawaii Filipinos for Marcos during his visit there.

At the airport tarmac, when Marcos was speaking, my former wife Sorcy, unfurled a big banner “Free All Political Prisoners.” The security person whom I befriended in previous events asked me to take her picture, which was also my assignment for the Ang Katipunan Newsmagazine. Since this was the first time that Marcos was confronted with a protest as close as 12 feet, he reacted by saying, “Hindi naman pala mga Pilipino.” (They are not Filipinos). Sorcy shot back and screamed: “P___ Ina mo..Filipino ako!” (F__k you, I am a Filipino!)

At the end of the publishers’ convention where Marcos spoke, I joined the picket line shouting “Marcos, Hitler, Dictador, Tuta,” to the surprise of many members of the Marcos entourage.

In every opportunity, on my own or with a group of fellow activists, we tried our best to denounce the dictatorship.

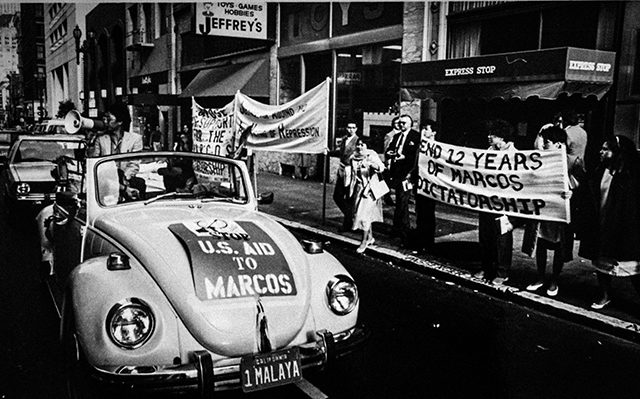

I disrupted the motorcade conducted by the Philippine Consulate General in San Francisco showing support for the dictatorship by using my company car to block their motorcade.

I photographed known supporters of the dictatorship when they showed up in our demonstrations.

I threatened a short pudgy Filipino photographer who worked for the government on Powell Street in San Francisco, and said he should be careful when he goes back to the Philippines because I had already sent his picture to the New People’s Army.

At the San Francisco International Airport arrival section, when a member of the local consular office arrived, I rushed back to my car to get my materials for sales presentations, and placed a huge banner on the counter of Hertz Rent a Car: “Down with Marcos Dictatorship.”

During Marcos’ state visit to the US in 1985, I went to the San Francisco Union Square early to check the security preparations for the demonstration to coincide with his speech in a nearby hotel. Filipino security officers were hanging out, talking about their plans in Filipino. At the height of the demonstration, I confronted one of the officers who was wearing an ear device, “Are you listening to the San Francisco Giants game or doing security work?” He immediately left the place.

I became front-page news item of the San Francisco Chronicle when the San Francisco Tactical Squad in front of the Philippine Consular Office beat me up with a baton when we tried to deliver a petition against Marcos. I was arrested and jailed for trespassing and assaulting a police officer. Inside the jail with regular detainees, when they found out the charges against me, they started clapping in support of my infraction. A national campaign was launched, and the charge against me was eventually dropped.

The training I learned in confronting authorities with or without a camera during martial law are valuable lessons I used later in my investigative photojournalism work.

Forty-four years after Marcos declared martial law, we must not forget the pain and suffering our people went through. Never again should we allow another Marcos to return to Malacañang. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.