SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Surveillance to deepen in Southeast Asia post-COVID-19](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/12/imho-surveillance-SEA.jpg)

The digital surveillance methods introduced to monitor, trace, and track populations in 2020 will deepen post-COVID-19. If privacy rights are not protected, state surveillance stands to regress democracy in Southeast Asia.

This was a key concern raised in Asia Center’s baseline study “COVID-19 and Democracy in Southeast Asia: Building Resilience, Fighting Authoritarianism” released on December 9, 2020 to mark United Nations International Human Rights Day. The 54-page report, compiled from July to November 2020, examines the state of democracy and human rights in the region from January 1 to November 30, 2020.

This concern over surveillance stems from governments monitoring populations over 4 key crises through two decades – triggered first by the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, followed by the 2001 September 11 US Terrorist Attacks, 2002-2004 SARS Outbreak, and 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. Collectively, these crises set in place a framework of state surveillance that is expected to be more intrusive and impact privacy.

There is emerging evidence that the youth, as they lead the charge for political reform around the region, are being surveilled and later arrested to neutralize them politically. Digital surveillance introduced by COVID-19 contact tracing is expected to become a long-term practice in the region post-pandemic. The youth are also expected to be the political targets of surveillance moving forward.

Since the introduction of contact tracing in Singapore and Vietnam during the SARS outbreak of 2002-2004, governments in the region have been able to design and implement mass surveillance that pinpoint and track individuals.

Contact and movement tracing mobile applications risk being used to track the movement of individuals and record private conversations as COVID-19 subsides. The longitudinal study cautions that the lack of clearly defined terms and conditions for these digital surveillance applications risk the long-term surveillance of citizens and residents in Southeast Asia, and may become the latest authoritarian residue.

Individuals are increasingly feeling distressed about voicing their concerns and opinions in private spaces, as the threat of being identified and prosecuted increases.

The government of Singapore has become more reliant on its state surveillance and policing, which have encroached on the privacy rights of those within its borders. The amalgamation of its TraceTogether and SafeEntry applications, and wearable tracking devices for foreign workers, have left little room for anonymity. Meanwhile, its POFMA “fake news” legislation has deterred the general public from speaking out, lest they risk fines of up to US$14,000 and/or a year in prison. Singapore, despite having the highest per-capita COVID-19 infection rate in Southeast Asia, has newfound success in repressing the rights of its citizens and residents under the guise of COVID-19 preventative measures.

Similarly, in Myanmar, the late introduction of the Saw Saw Shar application in September has expanded the reach of the government during mass lockdown. The agencies in charge, the COVID-19 Control and Emergency Response ICT, the Ministry of Transport and Communication, and the Ministry of Health and Sports, manage the data collected by the vague software. The application requires the user to grant access to their GPS location, photos, videos, files, and camera; however, users have noted the lack of updates on COVID-19 infections in the country. The absence of clearly outlining how the data is managed or stored is an additional concern.

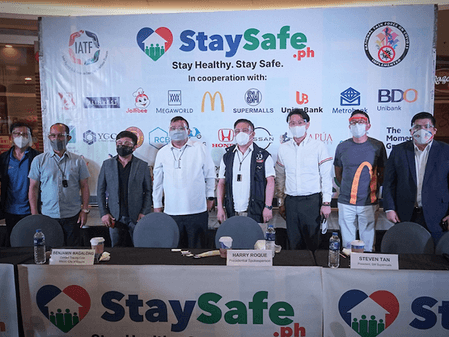

Indonesia’s PeduliLindungi, the Philippines’ StaySafe, Thailand’s Thai Chana and Mor Chana, and Vietnam’s BlueZone are among other applications which require the GPS location of its users. Brunei’s BruHealth and Laos’ LaoKYC applications, despite not accessing GPS, or clearly stating its ability, also collect the location and proximity movement of users. These often track the users’ movement and note contact points between individuals to the minute.

Moreover, the applications do not clearly outline how data is collected from users. Nor do they provide adequate information on the intervals in which data is captured. The concerns of these applications remaining active in the background have not been adequately addressed.

Less Vietnam, data of all applications are stored on government servers. Irrespective of the data stored on the users’ device or government servers, users have yet to be informed of the use of their data as COVID-19 infections subside and vaccines are introduced.

Will the data be deleted, anonymized, or stored after COVID-19?

The odds are not in favor of what individuals may hope for, in the case of Thailand and Malaysia. The Thai government in June verified leaked documents noting that contact tracing data had been shared, without consent of the user, between various ministries including the Ministry of Defense. Similarly in Malaysia, after its Gerak Malaysia application was terminated, the data at hand was not deleted but rather transferred to the Ministry of Health. In these instances, it is a reality that governments may store or transfer the information of individuals, especially those politically exposed and persecuted – to access permanently.

These movement and contact tracing measures risk becoming permanent as Southeast Asia enters 2021. Without abolishing these practices, politically active youth in particular risk becoming the most surveilled and curtailed generation of all time. – Rappler.com

Dr James Gomez is Regional Director of Asia Center – a not-for-profit organization working to create human rights impact in the region. Celito Arlegue is Executive Director of the Council of Asian Liberals and Democrats (CALD).

This opinion piece is adapted from Asia Center’s latest report, “COVID-19 and Democracy in Southeast Asia: Building Resilience, Fighting Authoritarianism,” released to mark United Nations International Human Rights Day, December 10, 2020.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[OPINION] We should own our health](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/thought-leaders-we-should-own-our-health.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=271px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] A big defeat for Big Tech](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/03/big-defeat-big-tech-march-27-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=425px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.