SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

If you think this newsletter is yet added fat to your online diet, I’d be the last to take offense. Like me, you probably have joined new chat groups shared by your neighbors, co-parents, relatives, officemates, schoolmates, and many others – where you drown in posts on where to order food, fruits, water, masks, humidifiers, gas, coffee, why, even milk tea!

The life we used to know is changing before our screens, and we comfort ourselves with the thought that this, too, shall pass. Will it?

Let’s look at some of the challenges that this pandemic is forcing us to face and which are changing our world in incremental ways. (In case you missed it, my last newsletter tackled the virus as one that’s reshaping our world.)

Challenge to leaders

If there’s anything the coronavirus did to President Rodrigo Duterte, it is to punch a big hole in his concept of an overreaching and strong government. His is the myopic, arm-twisting, slash-and-burn, bark-without-thinking type. Thus in this unprecedented crisis that begs for more but efficient and thorough government intervention, Duterte shrinks to a point of annoyance, that he’s almost now a midnight meme in our lives.

All he could think of is the predictable: special powers and more budget, both of which are prone to abuse. (Recommended read: Bayanihan Act’s sanction vs false info ‘most dangerous)

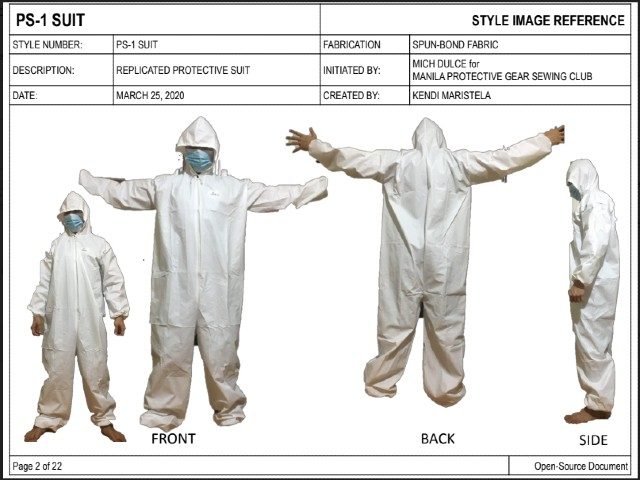

In contrast – because details, networks, and geography (yes, that, too) are her comfort zone – Vice President Leni Robredo has gone far ahead, raising P40 million as of Wednesday, April 1, on top of opening a dormitory for health workers, distributing kits and protective gear to thousands of health workers in various provinces, tapping Filipino fashion designers and the local mananahi to help make more, among others.

While critics might welcome this as Duterte’s possible Mamasapano, the cost for the nation is simply too much. At this point, since this phase is primarily now a logistics problem, let’s see how the generals – trained to deploy quick and fast – will run this. (Recommended read: Task Force gears up for massive testing)

Elsewhere, autocrats revealed their small-mindedness over the coronavirus, with no less than Brazil’s right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro initially dismissing it as just a “little flu” being used by his critics to “trick” Brazilians. Tanzania’s leader branded the virus “satanic,” something that, he said, will not thrive in places of worship. Others have used the crisis to tighten their already tight grip on power, like in the case of Hungary’s Viktor Orban, who declared a state of emergency with no deadline, and suspended all elections.

What type of leaders will a more complex, post-coronavirus world need?

Challenge to experts

Whether one is an expert in public health or data science or crisis management, the coronavirus demands more than what we have ever mastered in our lives. That’s simply the brutal truth.

Because aside from the absence of cure and the unraveling nature of the virus, the pandemic is occurring in a new world order – where technology has shrunk the world to reachable distances and businesses, and where distance has already become irrelevant. Today, we embrace distance in a new light.

A Harvard study suggests we should practise intermittent distancing for the next two years. And how distant is distant enough? An MIT researcher says the standard 6 feet is not enough, adding that droplets can travel up to 27 feet!

How could many experts have not foreseen this kind of global pandemic, or, in the instances when they have (such as Bill Gates’ 2015 warning),how could their prognosis been dismissed by policymakers?

Will we move to a stage where we’d be immune to it, as some have suggested? Former health secretary Manuel Dayrit told a Rappler PLUS briefing that immunity to the virus is “not completely understood” at this point. (For more webinars and briefings on the coronavirus and other issues, and to help support our journalism, please join PLUS via this link.)

A Quartz story on Wednesday, April 1, said the World Health Organization had, in fact, put in place, in 2015, a new set of guidelines on disease prevention and control, but that the world largely ignored them.

How will experts make sure they’re not only heeded by governments and people, but are also pushing the right buttons to be heard?

Challenge to journalists

The Koko Pimentel-Makati Medical Center fiasco on March 25 first erupted in chat groups before it reached newsrooms – screenshots of doctors’ messages to each other and patient information that hospitals would otherwise keep secret.

The “please be a model example” letter of the Dasmariñas Village head on March 28 to Senator Manny Pacquiao was leaked to reporters from the chat groups.

Suddenly, professionals, businessmen, other sources of information who are usually hard to get are speaking out, sharing insights and even fury. The once-meek voices in Viber groups dominated by administration allies are unleashing pent-up emotions and criticism of how things are being run.

What to do with such abundance of tips and information and fake news? It’s a real challenge to journalists’ attention and focus, because as they try to make sense of things and put stories in context, the numbers keep rising, the hospitals are bursting, people are dying.

How will journalists ensure that their first draft of history – verified, true, contextual, empathetic – is what is read, seen, and trusted by the public? (For all our stories, research and video on the coronavirus crisis, visit this page.)

Challenge to all of us

And how do we help each other keep sane in this environment? How do we deal with this uncertainty? What things and practices need to change? What sort of people should we become?

How should we lead and run our companies and manage our employees – as well as our households – as we battle this crisis and face its consequences?

Let me take this chance to walk you through the hard times we’ve overcome.

These are the heroes from the Philippine Army, who risked lives to rescue residents of New Bataan in Compostela Valley at the height of Typhoon Pablo in 2013.

Here is the barber of Guiuan, Eastern Samar, who lost everything to Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) in 2013 – the strongest typhoon to hit the world in recent memory – but who managed to get through and help fellow barbers rebuild their lives.

Who would have thought that once-ferocious Muslim rebels would set foot in Malacañang to sign a peace pact with the government? And who would have thought that the same rebels would play a key role in forming an expanded autonomous region that recently celebrated its first anniversary?

Look at how Filipinos crowdsourced aid for thousands of residents affected by the Taal Volcano eruption as we started year 2020.

And so, yes, this too may not pass soon enough. But we will, as always, overcome.

Have a meaningful week ahead! Appreciate your feedback at glenda.gloria@rappler.com. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.