SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

This compilation was migrated from our archives

Visit the archived version to read the full article.

(This newsletter was emailed to Rappler subscribers on June 22, 2020)

I could have alternatively titled this piece, “The Rappler Courage List.”

Here’s why.

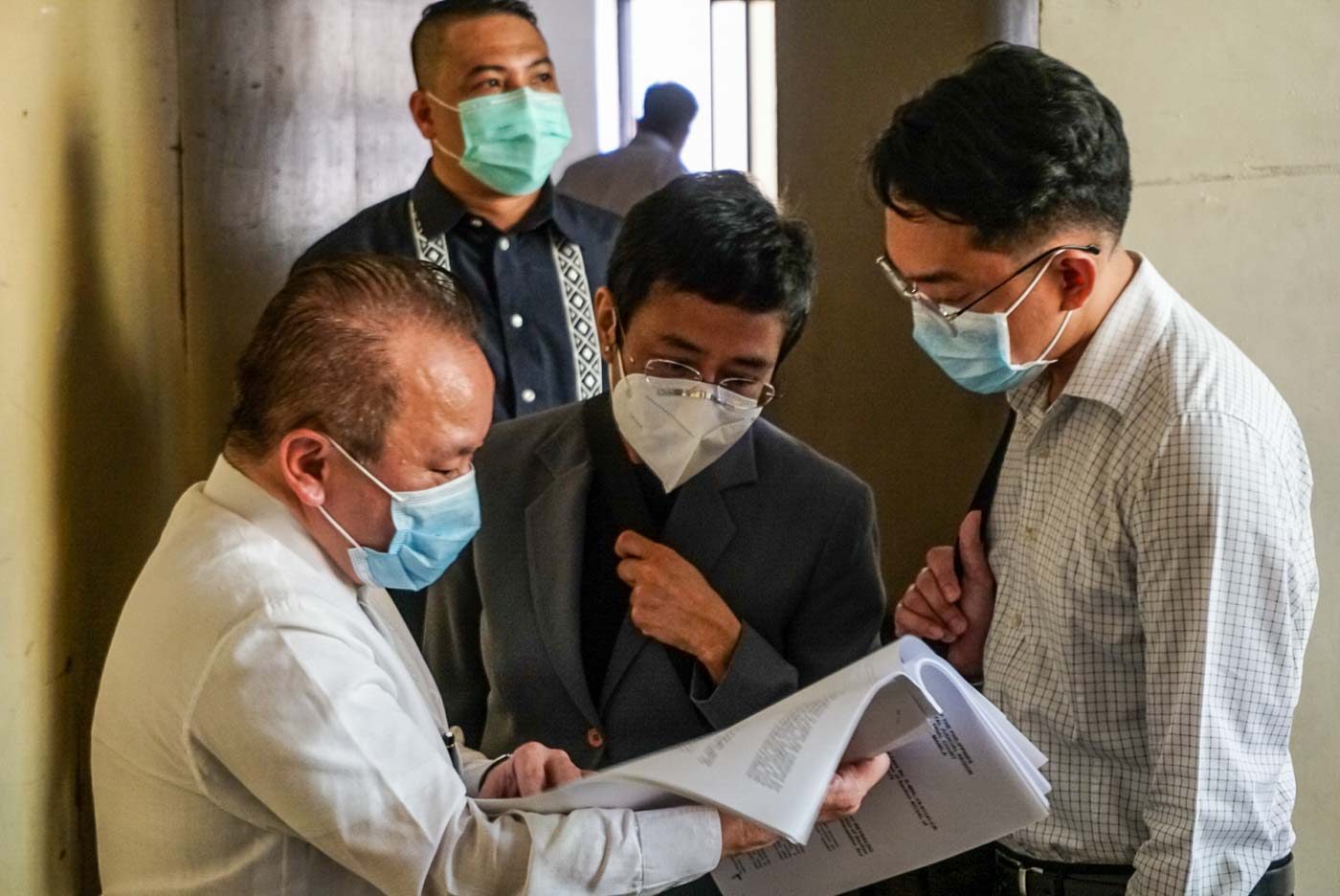

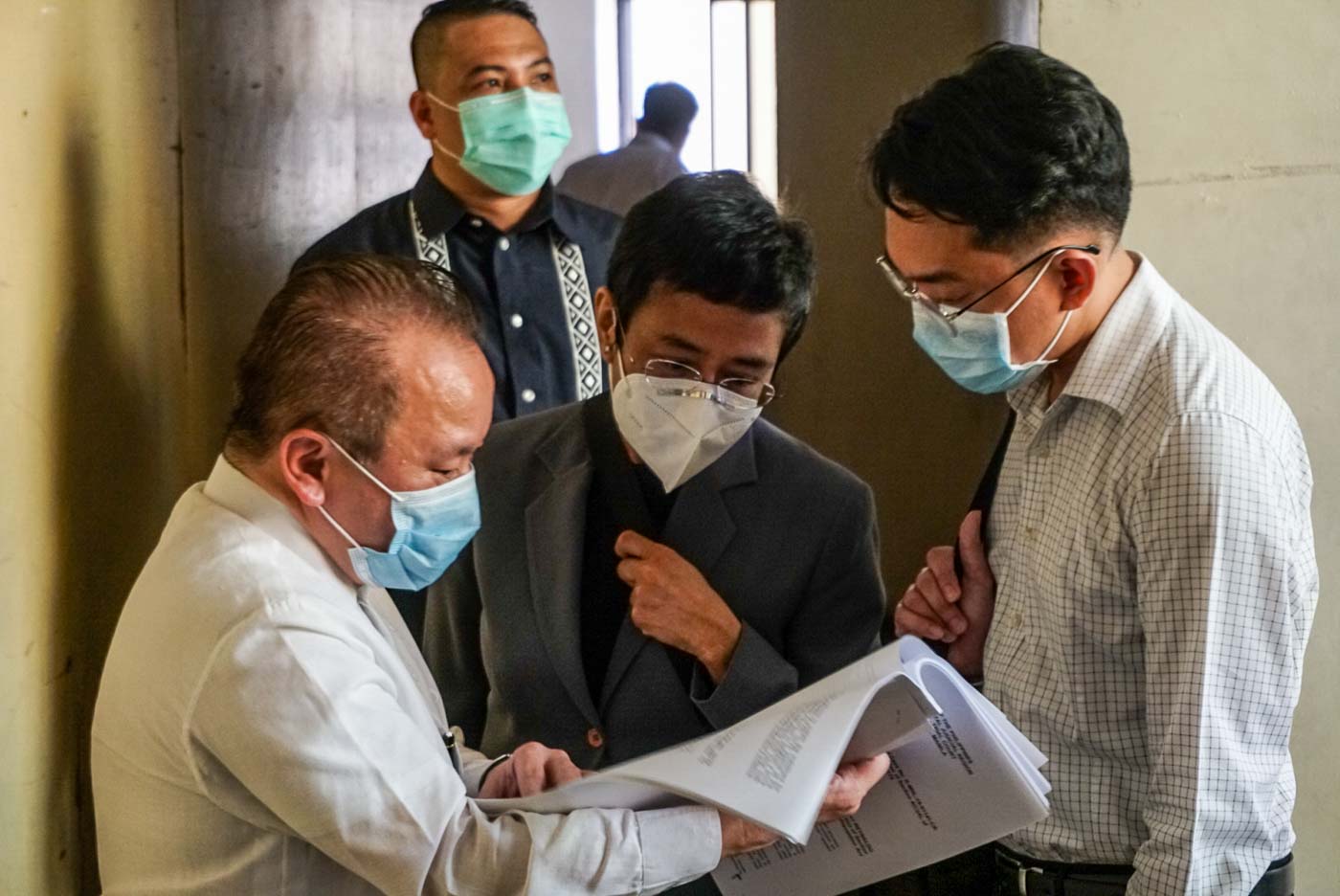

In a verdict condemned by local sectors, foreign governments, and international leaders like Hillary Clinton and Madeleine Albright, Manila Regional Trial Court Branch 46 Judge Rainelda Estacio-Montesa convicted Rappler CEO and executive editor Maria Ressa and former researcher-writer Reynaldo Santos Jr of the crime of cyber libel on Monday, June 15.

Instantly, conscientious and responsible media practitioners and legal experts saw the danger that the ruling posed to how independent journalism is done. The Inquirer’s John Nery called the verdict “nauseous” and the judge “ignorant.”

The judge subscribed to the glaring legal acrobatics of government prosecutors (the justice department filed the case on behalf of businessman Wilfredo Keng) and gave credence to the assumptions of the complainant’s lawyers about how newsrooms work.

Examining the issue of press freedom and responsibility in the vacuum of Keng’s case, she now also threatens to upend the long-held ways that journalists in the Philippines and around the world put together investigative reports.

The ruling is practically saying:

- You can’t cite unnamed sources, because that would make the story not trustworthy, and therefore makes you fair game for libel.

- If presented with an intelligence report that proper authorities already vetted and use as a guide in their operations, and whose authenticity you’ve also validated, you have to verify yourself the very acts alleged in there before you can cite the document.

If these become rules – they will if the verdict is upheld when our appeal reaches the highest court – how more difficult would it then be to expose influence-peddling and lobbying in government, abuse of power, corruption, betrayal of public trust, and, in some cases, even treason?

And we’re not only talking of Rappler’s work.

WHAT THE VERDICT MEANS FOR JOURNALISTS AND NETIZENS

- Court affirms republication a separate libel offense, prescription period is 12 years

- What Maria Ressa conviction means for reporting confidential sources

- International media groups denounce Ressa, Santos’ conviction

- Judge Montesa ‘failed to understand how journalism works’

- After ruling vs Ressa, uploaded old print articles vulnerable to cyber libel

- Aquino’s contested cyber libel law gets new claws in ruling vs Rappler

- Law experts: 12-year prescription period for cyber libel unconstitutional

THE MORNING AFTER: SOME PRACTICAL QUESTIONS

Reporters have immediately started feeling the effects of the verdict. Confidential sources are now split between those who’d relegate them to the “Seen” zone and those who have strengthened their resolve to provide us with leads, documents, and briefings. There are those who are afraid they’d be dragged into future harassment libel cases against Rappler and those who continue to trust us to protect them as sources (thank you, too, Expanded Sotto Law).

Even government officials, who would normally speak on record to them or to any news organization, are reluctant to do so now – just keeping a safe distance in case Malacañang suspects they are sending a message of defiance against an administration ally. What else could they make of President Rodrigo Duterte’s spokesperson having taken it upon himself to defend the verdict that favored the “private” person who supposedly doesn’t have any connection to the Chief Executive? (READ: Who is Wilfredo Keng? | Duterte gives Wilfredo Keng’s daughter a government post)

(Care for a trivia? When media practitioners – among them, Rapplers – were protesting the passage of the cybercrime law under the Aquino administration, one of the human rights lawyers who sounded the alarm on how the law would trample on press freedom was Harry Roque. Even threatening to sue then-president Benigno Aquino III over the presumed unconstitutional law, Roque is now Duterte’s spokesperson denying the President’s attacks on the press.)

Reporters are also thinking:

- Will the public, from now on, dismiss as not credible the confidential documents that journalists get from official sources just because they don’t divulge who exactly provided them?

- Will their stories be perceived as not solid enough just because the documents are confidentially sourced and they cannot reveal how they acquired them?

- How do we report now on government investigations of and complaints against private persons who are considered in the public domain because either the information on them is being processed by investigative agencies or their activities are imbued with public interest?

- Should we go back to stories from more than a decade ago that were based on confidential/sourced documents and reports – to get an idea which of the persons we wrote about might just spring to life and file a libel complaint?

- Should we keep detailed notes of how we put together every single story and keep for the next 12 years, just in case some subject decides to go to court on the 12th year and the judge pounds on us to recall every detail of our work?

- Assuming there were lapses in a story, are lapses now the basis of malice? (Press One’s Manny Mogato has an informative take on this issue: “Absence of malice.”)

Pia Ranada, who wrote some of the followup stories on Keng, points out the need for us journalists to double our efforts to educate the public on why it sometimes becomes necessary to keep sources anonymous, to let documents speak for themselves without incriminating the official or the office that provided them.

“People assume that when the source is unnamed, the story is just some malicious rumor. Sometimes that’s the only way to hack at the truth,” she says. We need to show them that anonymous sources and intelligence reports are a last resort, but that there are “working systems [within the newsroom] to safeguard against the abuse of this practice.”

Lian Buan got an advice from a Twitter follower“never to quote a confidential source, to always wait for someone to put their name to [the information], so if it unravels later on, the source will be the one in trouble.”

Our justice reporter won’t have any of that: “I think that is a disservice to both our audience and to the sources who risk their careers to tell the truth. Our platform and the power of the media have given us a protection blanket so we can afford to be courageous to quote an unnamed source, who’s also as courageous to even talk to a reporter in the first place. Media has assumed that role, to be in the line of fire, because unnamed sources are already risking enough, and to be told to back off from this line of fire, just to be safe, is hard to accept.”

OUR #CourageON LIST

The reporters have listed some of their in-depth stories from recent years which we couldn’t have put together if we didn’t agree to grant sources anonymity or if we didn’t use confidential documents whose authenticity we had vetted:

- In Bilibid, dozens die of unclear causes without being tested for coronavirus

- ‘THREE TIMES THE STRUGGLE’: On lockdown with children with autism

- Probably not 3,000, but Chinese agents are around us – intel experts

- Drug war poster boy Jovie Espenido is on Duterte drug list

- Multi-billion SEA Games 2019 fund follows Cayetano where he goes

- BCDA, Malaysian firm ink questionable P11-billion SEA Games deal

- Final PCG-Marina report: Chinese ship failed to prevent sea collision

- UNTARNISHED TRUTH: Pisay students spark a campus movement vs sexual harassment

- Pisay boys who shared lewd photos barred from grad rites

- Ex-cop Acierto speaks out: Duterte, PNP ignored intel on Michael Yang’s drug links

- Auditors flag P3.6B in Philippine Coast Guard transactions

- The women behind the fall of Alvarez

- P1-consultant runs Tourism Promotions Board besides Cesar Montano

- NFA’s Aquino diverted E. Visayas rice to Bulacan rice traders – memo to Duterte

- The secrets of Ruby Tuason

These are the kinds of reporting that Judge Montesa’s ruling threatens to prosecute, if not altogether discourage even before work on them starts. Not that Rappler will be cowed into avoiding anything like them. We just want the public to realize that the menace extends to similarly probing content by other news outlets, whether in print, broadcast, or online.

SOLIDARITY

Montesa’s ruling is by no means final and executory, and we intend to appeal it even if we reach the Supreme Court. But in the face of this threat to our practice – and amid taunting by President Duterte’s supporters and Rappler’s critics – the solidarity among like-minded journalists is forged further, observes Rambo Talabong.

“I’ve been able to share contacts with fellow reporters without that shroud of competition hanging over us as heavily as before,” he says, because they know who the enemy is, and it’s not one another.

In a piece for the Inquirer, tech firm manager Kevin Mandrilla noted that the prosecution and conviction of young former journalist Rey Santos Jr could be an attempt to “[make] an example of him to send a message to the most critical and loudest among the critics – the young idealistic people….” Yet the opposite might be happening, that it would give the young people the “impetus to come together. Just look at the mess we are inheriting. Now more than ever, we need to weave threads of solidarity, especially at a time when the fight of an individual has symbolic importance.”

I don’t know about the others in the industry, but when such a community of interest forms, when the ones in the trenches find a singleness of purpose, it is not us journalists who should be running scared. – Rappler.com

Until my next newsletter! Email me your thoughts at miriamgracego@rappler.com. If you want to help Rappler pursue in-depth reports on specific sectors and issues, you can donate to our investigative fund here. You can check out the conversations I engage in on Twitter @miriamgracego and follow the stories I share on Facebook.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.