SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

The first email came just 3 days after Rappler released part one of an investigative series on abortion.

The 3-part series I penned for Rappler explores the dangerous practices of backstreet abortionists, delves deep into an online forum where women seek abortion services, and reports about a group of underground doctors who do the procedure safely – but in top secret. In Catholic-majority Philippines, abortion is deeply stigmatized and strictly illegal.

The email I received, dated Thursday, August 16, was 800+ words long. It was studded with YouTube and article links, and while there was no personalized note except for “Ms. Natashya Gutierrez” in the beginning of the email, the message was clear: the sender denounced my piece.

The sender sent links to “the teachings on the Antichrist in the Cathecism of the Catholic Church” and a piece on a person converting to Catholicism. The email quoted a book, saying “the media have conditioned society to listen to what it wants to hear,” and said Quebec is self-destructing because of low fertility rates.

And, as with any ultra-religious message, it took the chance to denounce homosexuality – even when it was completely unrelated to the topic.

I’ve been used to receiving hate messages, death threats even, accusations of being anti-Christ for voicing more liberal perspectives, and expected more to come. As if conditioned from years of online harassment, I was unbothered.

But that was the first and last of those type of messages. I was not prepared for the emails that followed.

Since the first part was published on August 13, I have received a consistent stream of tens of messages on various platforms – via email, and on my personal Facebook and Instagram pages – from a slew of Filipinos of various ages. They come from different parts of the country – Manila, Laguna, Davao – and while most are from women, I’ve also received a couple from men, messaging in behalf of their pregnant partners.

All were desperate cries for help: where – they begged – could they find the safe abortionists, the underground doctors, I wrote about?

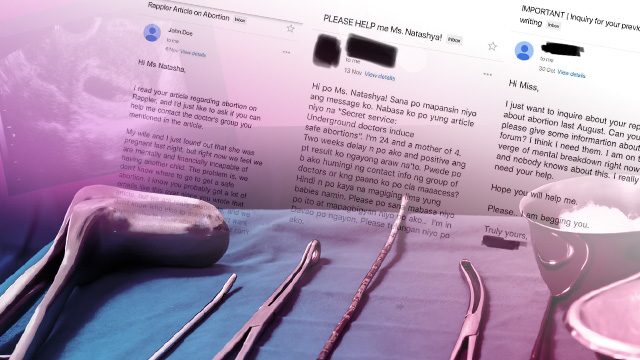

‘PLEASE HELP’

You could hear the despair from the email titles alone.

One was in caps, with my name spelled out: “PLEASE HELP me Ms. Natashya!”

The sender was a 24-year-old mother of 4. She explained that having a 5th child was not feasible for her family.

Another wrote me 4 times: “I am on the verge of [a] mental breakdown right now and nobody knows about this. I really need your help. Hope you will help me. Please… I am begging you… I badly need this.”

One other woman said she needed the contact of doctors who would help her, or else she’d have to risk her life with backstreet abortionists.

Some, completely at a loss, found an ally in me, sharing their stories.

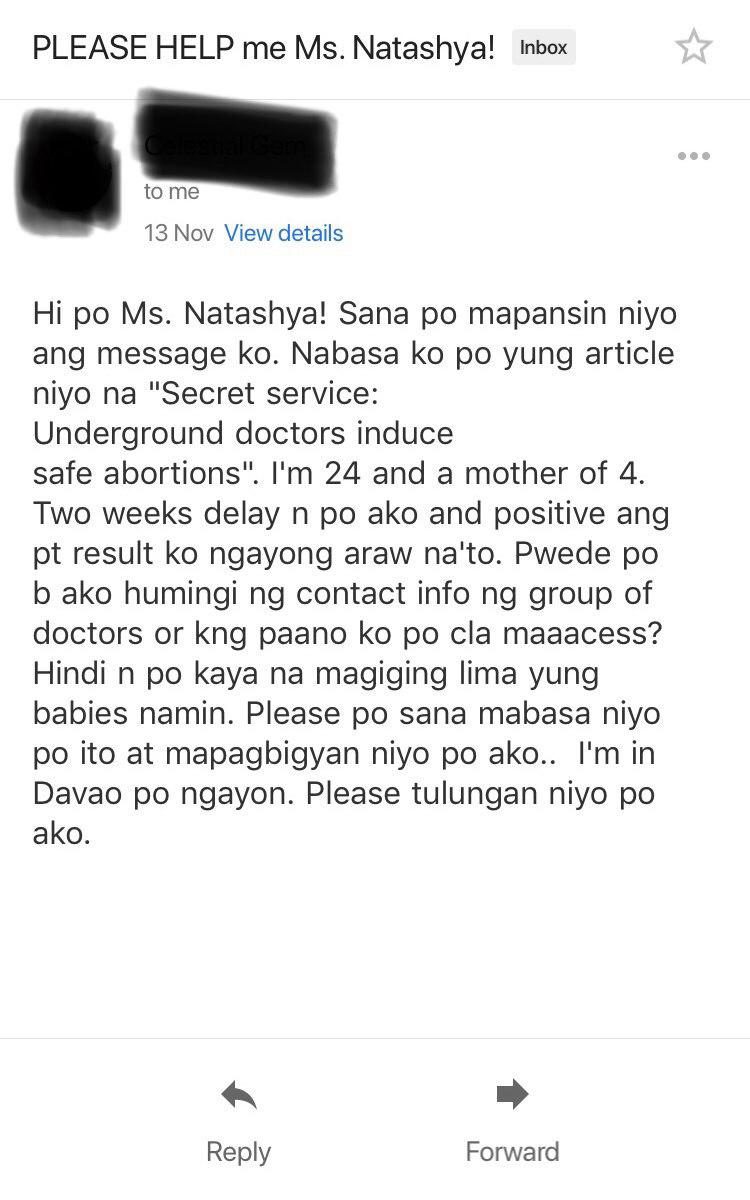

“My wife and I just found out that she was pregnant last night, but right now we feel we are mentally and financially incapable of having another child. The problem is, we don’t know where to go to get a safe abortion,” said one sender.

“I know you probably got a lot of emails like this ever since you wrote that article, but we are really desperate, and we don’t know who else to ask. We don’t want anyone else to know about this, so we can’t ask any of our friends.”

Another man shared his predicament. “Your article gave us hope that there is a way for us to be helped out by medical professionals that will check on the medical status of my girlfriend even after the procedure,” he wrote. “I hope that you can help us out with this endeavor.”

And still another young woman: “I can share my story how this happened and how this guy left me alone without anyone knowing, [not] even my family about this. I know it’s my fault that I trusted him. Please help me.”

Yet the most striking email was from a young, 15-year-old teenage boy, sent in the evening of November 20.

“My girlfriend (soon-to-be partner may face an unwanted pregnancy. She’s delayed for almost two months. We will do pregnancy test on Thursday to confirm),” he wrote. “We are still a student and not yet ready to have a child. Due to that, I’m thinking of going to Quiapo to look for recommendations where we could meet people that can induce abortion (unsafe and illegal).”

Quiapo in Metro Manila, is notorious for backstreet abortionists and for selling dangerous abortion pills and concoctions.

“But, of course, I cannot manage to risk it. My girlfriend’s life is at stake and I will not let anything bad happen to her,” he said. “I know the confidentiality of their identities and services must be remained, but we’re talking about life here.”

He then added, in all caps and in Filipino, “I AM HOPING TO ASK FOR INFORMATION ON HOW WE CAN CONTACT THE DOCTORS OR THEIR SECRETARY.”

(UMAASA PO AKO NA MAKAHINGI NG INFORMATION KUNG PAANO PO NAMIN MAKO-CONTACT YUNG DOCTORS OR THEIR SECRETARY.)

“I look forward to hearing from you soon.”

Paranoia, sadness

The notes were from strangers who had no one to turn to but me, another stranger – in what could be the most difficult time of their lives. They felt like secret mail – raw, personal writings that I didn’t have the right to see.

The messages broke my heart.

I teetered between paranoia – were these underground cops, waiting to arrest me if I referred them to abortionists? – sadness, and anger. And always, sympathy. It was painful to read their notes, sent in hopes of a response, to a person they had never met, never spoke to, wondering if I had received them.

I did. To all those who sent letters, I did.

Though I want badly to reply and extend my help, I am aware that even referrals to abortionists are illegal in the Philippines.

I went so far as to get a lawyer’s advice. The lawyer warned me to be “generic, safe and provide sufficient tips.”

The lawyer suggested a reply encouraing them to research international reproductive rights organizations, go to countries where it is legal, ask OB-gynecologists for referrals, or to seek crisis counseling from NGOs.

Nothing specific, nothing direct, no names or contact information – for the safety of both myself and the senders.

It frustrates me that there is nothing I can do for them, and for this, I am sorry to those who wrote.

What now?

I’ve spent many days thinking of the senders behind these notes. I think of them often, the women, their partners, their health.

Are they okay? Did they choose other, less safe options? How far along are they now, if at all? Will they find the doctors I wrote about? Do they check their emails, their Facebook, their Instagram, hoping to hear from me?

I am saddened that because of the profound stigma against abortion and the restrictive abortion laws of the government, they cannot seek help from friends or family or their doctors or the state – they have to turn to a journalist.

Is this the Philippines we want? One that ignores the desperation and the pleas of young women who are not ready for children, whether emotionally or physically?

One that judges and stigmatizes pregnant women?

One that decides what a woman can and can’t do with her body?

Amid the notes of distress, I managed to find a ray of light in one email. The note was signed with the sender’s full name, telephone number, and hospital address.

“Good morning Ms. Gutierrez!” it started. “I came across your article and would request for a contact number to these group of doctors.”

It added, “I am a doctor wanting to help some patients in their needs.”

As with all the other notes, while I cannot reply with the answer they want to hear, this, at least, gave me hope. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.