SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

On Monday, November 16, when 17 world leaders began to arrive for the APEC Summit in Manila, a video of men in masks with ISIS’ black flag behind them is posted on Facebook, claiming “ISIS in Mindanao” will attack the summit.

Authorities dismissed it, but by evening, it had reached nearly 2 million views.

Col Resty Padilla, spokesman for the Armed Forces of the Philippines, asked the public to ignore it and avoid sharing it.

“There’s no threat,” he told journalists. “So far, the monitoring indicates that there are no serious threats that will hamper the conduct – successful, peaceful and secure conduct of this summit.”

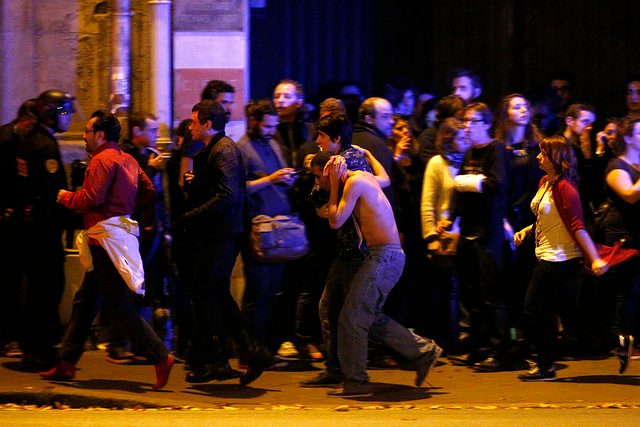

Still, authorities are on high alert, and intelligence sources say they are investigating the video, released just a little more than 2 days after 3 teams of suicide bombers and gunmen across 6 locations in Paris killed at least 129 people and injured at least 329 more.

The near simultaneous attacks, reminiscent of Mumbai in 2008 when 10 armed gunmen attacked 7 different locations, shocked the world. Much like 9/11, it seems to signal an escalation in jihadist terrorism that has its roots in the virulent ideology that powers al-Qaeda and its latest incarnation, ISIS.

An al-Qaeda offshoot that has overtaken its parent, ISIS, also known as the Islamic State or IS, ISIL, and Da’esch, a loose Arabic acronym, seems bent on taking the world back to the 12th century. It has a fundamentalist interpretation of the Koran that includes savage beheadings, rapes, and public executions designed to eliminate “unbelievers” in a process it calls takfir, or excommunication.

Key to its power is something al-Qaeda was never able to do: it captured and governs land roughly the size of Great Britain. That is the capital of the global caliphate it says it is creating – acting like a beacon and bringing in at least 30,000 foreign fighters in a little more than 3-and-a-half years, according to latest US and UN estimates.

Despite its economic focus, terrorism and security issues are among the main topics to be tackled at APEC this week in Manila.

There are 4 lessons Paris teaches us, which Philippine authorities should keep in mind as it hosts 17 world leaders this week.

1. It’s war. And it’s global.

Within hours of the Friday attacks, France’s President Francois Hollande called them “an act of war waged by a terrorist army, a jihadist army, by Da’esch, against France.”

Except war began decades ago. And it’s escalating.

The US, leading a coalition of 65 countries, jumped in more than a year ago to try to defeat ISIS and its offshoots.

On the sidelines of APEC, US Deputy Secretary of State Tony Blinken told me ISIS now controls “30-35% less territory than a year ago” but that action comes with risks. (Watch the Blinken interview here)

“We saw that if this problem was not arrested as quickly as possible, it was likely to spread,” said Blinken. “And indeed ISIL had ambitions to attack not just in the region but in Europe and the United States and places beyond. We understood from the beginning that it was part of their larger objective.”

Paris brings the war to coalition countries where they live, a logical extension of an ideology that matured in the conflict in Afghanistan in the late 80s.

That gave rise to al-Qaeda, and ISIS is its latest incarnation.

“Al-Qaeda is a kindergarten group compared to ISIS,” Rohan Gunaratna, the author of Inside Al-Qaeda and the head of Singapore’s International Centre for Political Violence & Terrorism, told Rappler. “ISIS presents an unprecedented global threat. ISIS is a hyper-powered organization. We have not seen a group of the scale and magnitude of ISIS.”

ISIS began its march to capture Baghdad on June 9, 2014, and it has grown tremendously since then: capturing oil fields for resources; creating and implementing laws it implements for the land under its control; and harnessing affiliates for global attacks.

Shortly after the Paris attacks, former FBI agent and author Ali Soufan summarized the escalating death toll and pace. He tweeted that in the last 36 hours, there were 18 victims in Baghdad, 43 dead in Beirut, and 153 in Paris – “all murdered by the same narrative of takfir and terror.” (Takfir, which sanctions violence against Muslim leaders who are kafir or are unbelievers).

In the past 36 hours: #Baghdad: 18 victims #Beirut: 43 victims #Paris: 153 victims All murdered by the same narrative of takfir & terror.

— Ali H. Soufan (@Ali_H_Soufan) November 14, 2015

On November 13, a suicide bomber killed himself and at least 17 others at a Baghdad memorial service for a Shiite militia member who died fighting ISIS.

In Beirut, Lebanon, two suicide bombers killed at least 43 people during rush hour at a busy shopping district in a mostly Shiite residential area. The body of a third suicide bomber was found near one of the blast sites with a largely intact explosives belt. ISIS claimed responsibility for that fiery attack.

This is the second time in two weeks that ISIS claimed attacks against civilians, its effort to get back at the countries fighting it in Syria and Iraq.

ISIS’ Egyptian affiliate said it was responsible for the Oct. 31 destruction of a plane full of Russians coming home from vacation at the Sinai Peninsula in Egypt. Why Russians? Because Moscow intervened in Syria.

On Tuesday, Nov. 17, Russia announced for the first time that a bomb destroyed the plane.

Now add Paris.

France is one of the founding members of the US-led coalition that began airstrikes against ISIS. These attacks come after the brutal Charlie Hebdo murders early this year carried out by gunmen claiming allegiance to ISIS and an al-Qaeda affiliate.

Still, it isn’t just ISIS attacking. This war is in full swing and escalating.

Last week, the United States and its allies announced it had sharply increased airstrikes against ISIS’ oil fields in Syria, making it perhaps the wealthiest terrorist organization globally. The US Treasury Department estimates the oil fields ISIS controls generates about $40 million a month or nearly $500,000,000 a year.

A day before the Paris attacks, Kurdish and Yazidi forces, backed by US special forces and airstrikes, liberated the strategic Iraqi city of Sinjar – cutting a supply route between its Iraqi stronghold in Mosul and its capital, Raqqa, Syria.

At nearly the same time, the US announced a drone strike seemed to have killed one of ISIS’ best-known militants, Mohammed Emwazi, the British executioner better known as Jihadi John.

That same Friday, President Barack Obama told ABC News that “we have contained them” referring to ISIS.

That symbolic victory lasted only a few hours.

Yet as the Paris attacks were happening, the US was broadening its fight against ISIS in Libya, targeting and allegedly killing its senior leader Abu Nabil. He was an Iraqi national who led al-Qaeda operations from 2004 to 2010.

By Tuesday, France and Russia had intensified bombing operations against ISIS.

2. Southeast Asia is a key recruitment center for ISIS.

As of mid-2015, more than 500 Indonesians, including women & children, and more than 50 from Malaysia have joined ISIS, according to regional intelligence officials. There are enough Indonesian and Malaysian fighters that they are in an ISIS unit by themselves, the Katibah Nusantara (Malay Archipelago Combat Unity).

“ISIS posted a propaganda and recruitment video showing Malay-speaking children training with weapons in ISIS-held territory,” Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said mid-year.

“Two Malaysians, including a 20 year old, were identified in another ISIS video of a beheading of a Syrian man. The Malaysian police have arrested more people who were planning to go, including armed forces personnel, plus groups which were plotting attacks in Malaysia,” added Lee. These individuals were going to Syria and Iraq not just to fight, but to bring their families there, including young children, to live in what they imagine, delusionally, is an ideal Islamic state under a caliph of the faithful.”

Indonesian Abu Bakar Ba’asyir, the spiritual leader of Jemaah Islamiyah, which in the late 90’s to mid-2000s acted as al-Qaeda’s arm in Southeast Asia, pledged allegiance to ISIS last year.

ISIS said it wants to establish a wilayat – a province under its caliphate – in Southeast Asia. While some will dismiss it as far-fetched, that’s its stated goal. (READ: Q&A: ISIS in Southeast Asia)

3. ISIS’ ideology is in the Philippines.

Be careful of names. Follow the ideology.

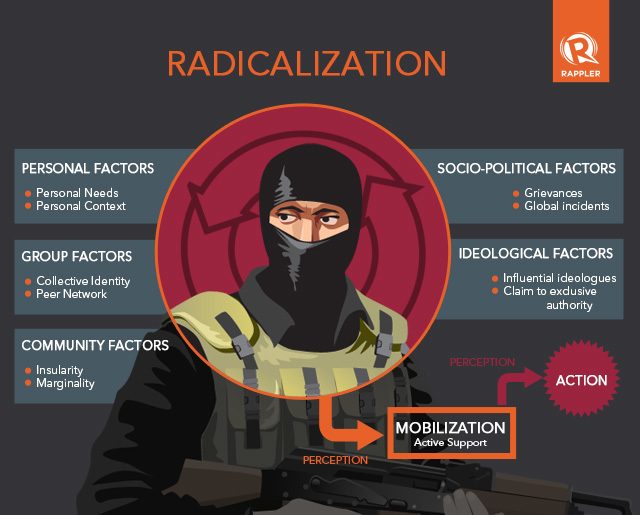

Follow the virus. Because like a virus, the ideology creeps in beneath the surface and takes over the system until it hits a tipping point. Lessons from epidemiology give us a paradigm for ISIS’ strategy: infect until it takes over the system.

Filipino and US security forces and authorities say ISIS doesn’t exist in the Philippines because they look for direct operational links to Syria and Iraq. Still, as early as 2011 al-Qaeda’s black flag, appeared in the Philippines behind a Filipino speaking fluent Arabic asking to bring the jihad to Mindanao.

That flag has become ISIS’ banner, originally brought to Syria and Iraq by foreign fighters, but over the last year and a half, it has become a rallying symbol. (READ: 14 years after 9/11 in Southeast Asia)

As early as 2012, I reported that authorities found the black flag in an Abu Sayyaf camp in Zamboanga. Interestingly, the man arrested then, Khair Mundos, who links the Abu Sayyaf to a global network, was sentenced to prison Monday, November 16, 2015.

The flag is only a symbol of groups of Filipinos who believe in the ideology that powers al-Qaeda and ISIS. In my latest book published at the 10th anniversary of the Bali bombings, I talked about a jihadi virus that uses religion as a vehicle for political power. That goal of setting up a caliphate hasn’t changed, and based on their own statements, they want to expand it beyond Syria and Iraq.

Last year, a senior leader of the Abu Sayyaf as well as another charismatic leader of an offshoot, the Rajah Solaiman Movement (RSM), pledged an oath to ISIS, something dismissed by most Filipino security officers.

US and western authorities have long talked about attacks by lone wolves, where all it takes is one man to turn his gun on a crowd. These attacks have happened in the US, Europe and other parts of the world.

Now Paris brings the spectre of potential central coordination from ISIS.

While the attacks were still playing out in Paris, President Hollande said, “This act of war was prepared and planned from the outside, with accomplices inside.”

It’s a new development that shouldn’t have been unexpected, turning what analysts called “lone wolves” into satellite forces capable of being synchronized for larger attacks.

“The emphasis on lone wolves was all part of the wishful thinking that ISIS was purely a local phenomena that could be contained to Syria and Iraq,” said Bruce Hoffman, director of the Center for Security Studies at Georgetown.

That threat of small yet effective terror cells loosely directed by ISIS blasts through many existing counter-terrorism measures.

With this, we can look at the Facebook video released in the Philippines Monday, November 17, as intent. The next question is do they have the capability? Security forces say no, but what exactly does capability mean now in the age of ISIS?

4. ISIS is a master at social media.

ISIS posts more than 200,000 pieces of content on social media every day, and it’s been successful in radicalizing marginalized and disenfranchised youth around the world.

“Social media is a critical front in this because the narrative that ISIL projects, it uses social media to project that narrative,” Blinken told Rappler.

A study released early this year said there are a minimum of 46,000 Twitter accounts used by ISIS, according to Intelwire’s J.M. Berger, who did the study commissioned by Google and published by the Bookings Institute.

ISIS aims to disrupt, carve out young minds and voices and offer a paradise that doesn’t exist. It has enticed young women, some as young as 15 years old, to join the jihad in Syria. (READ: How to fight ISIS on social media)

One of ISIS’ key supporters and propagandists, Melbourne-born Musa Cerantonio, lived in Manila, Cebu and Zamboanga for more than a year and was tweeting incitement and support to help ISIS.

A study mid-year said Cerantonio was one of the two most influential voices giving ‘inspiration and guidance” to foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. It added that one in 4 foreign fighters followed Cerantonio’s Twitter, account and that more than 92% of his tweets involved interaction. His Facebook page was the 3rd most popular among foreign jihadists.

To fight the pull of the ideology amplified and given wider reach by social media, countries and civic society must work together. (READ: How to fight ISIS? Build communities)

This war, as it always has, goes beyond armies, police and security forces. This war demands greater transparency and cooperation between communities at a global scale with these key goals: to reject sectarian strife; separate terrorists from Islam; address grievances, including political and economic ones, that lead to marginalization; give the youth opportunities; and, avoid “us” and “them” by building inclusive communities.

That is the challenge ahead. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.