SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

Perhaps the only thing worse than a natural disaster is a man-made one, often borne of misguided policies that favor a few entrenched interests, while placing most of the risk and cost of failure on the broad population.

Add human rights abuses and a complete monopolization of political power and you have the ingredients for an economic and political implosion.

Drawing on the available evidence, the economic disaster that began in the late 1970s and ultimately helped to end the Marcos dictatorship in 1986 is one glaring example of what a man-made disaster looks like.

At the time, the country’s top economists, the majority of the business community, the perhaps millions of Filipinos voting with their feet to leave the country, and indeed the international community all recognized the role of the Marcos dictatorship in the disaster that would ensue.

Perhaps young voters today cannot be faulted for failing to see in full the economic and political folly of a dictatorship. This article is meant to reach out to them, in an attempt to clarify – using evidence – the true economic record of the Marcos dictatorship.

Sick man of Asia

Decades of policy experience and evidence in international economic development policy suggest that countries succeed if they get (at least) two things right:

- They put in place the right policies and institutions such as those that spur investments, strengthen government accountability and empower citizens;

- They successfully convince the majority of the population (and also unify much of the government bureaucracy) in a single-minded quest to develop and industrialize.

Examples of East Asian tiger economies such as Indonesia and Malaysia show what effective economic development policies combined with able leadership and a united citizenry look like. Between the 1960s and the present, Indonesia’s real GDP per capita (in 2005 US dollars) increased around six-fold, while Malaysia’s increased by roughly seven-fold. And while both countries experienced economic challenges during the Asian financial crisis of the mid-1990s, Malaysia recovered its pre-crisis GDP per capita after 3 years and Indonesia after 7 years, promptly returning to its upward trajectory afterwards

Make no mistake: Malaysia and Indonesia (like many other Asian tiger economies) also produced authoritarian leaders. But political scientists and development researchers contend that in these countries, there was still a general inclination to preserve legitimate political regimes in large part through inclusive economic development.

The Philippine experience is a study in contrast to these tiger economies.

First of all, the country only managed around a two-fold increase in its real GDP per capita between the 1960s and the present. The bulk of the story behind this lies in the economic meltdown during the tail-end of the Marcos years, coupled with a long road to recovery by the “sick man of Asia”.

And unlike Indonesia and Malaysia that managed to bounce back from their respective crises in only a few years, the Philippines languished below its pre-crisis income level for around 2 decades, recovering its real GDP per capita in 1982 only in 2004.

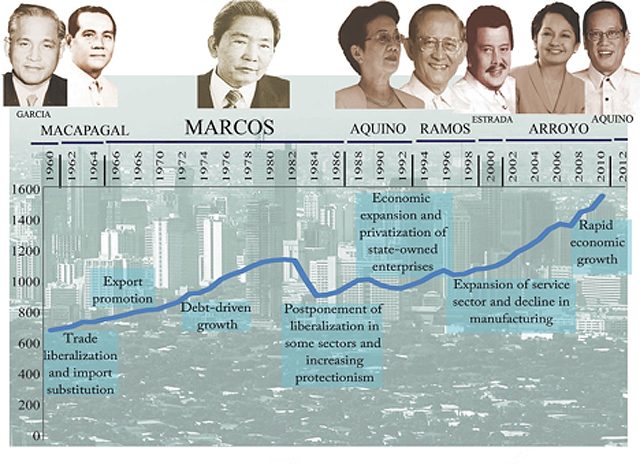

Figure 1. Philippine Real GDP Per Capita (2005 US dollars), 1960-2012.

What went wrong?

Put succinctly, some of the country’s top economists have characterized the Marcos years as being fueled by “debt-driven growth.”

Debt is not necessarily detrimental to a country’s economic growth and development, when managed well and invested judiciously – notably in areas that allow the country to grow faster and include more of its citizens as beneficiaries and drivers of that inclusive growth.

Indonesia and Malaysia managed to do this. Both countries reduced poverty during their industrialization periods. Indonesia started with 70% poverty incidence in 1970s, driving this down to a mere 15% by the 1990s and further to around 11% in 2013. Malaysia also managed to reduce its 50% poverty incidence in the 1960s to less than 1% today. These economic results helped to legitimize their political regimes—a form of accountability that political scientists and development researchers attribute to the Asian tiger economies.

Philippine poverty, on the other hand, increased during the Marcos years, rising from 41% poverty incidence around the time Marcos took the Presidency in the 1960s to around 59% by the time he was kicked out by a popular people-power revolution in the 1980s. And during this time, as much of the country was impoverished, the country’s external debt grew by an annual average rate of 25% from 1970 to 1981.

Failures of economic management

If there was so much money flowing into the country, then why did poverty continue to increase?

An influential think piece written in 1984 by Noel De Dios, Vic Paqueo, Solita Monsod and other top economic minds of the country then, outlined the many failures of economic management during the Marcos years.

State-run monopolies, mismanaged exchange rates, imprudent monetary policy and debt management, all underpinned by rampant corruption and cronyism, were among the key factors that plunged the Philippine economy into the worst economic contraction that it has experienced in its entire history.

For at least a while, such was the authoritarian control of the dictator that many of the excesses in the form of captured and corrupted state policies were unchecked. Such was the centralization of power and impunity that there was little inclination to preserve the legitimacy of the regime by reducing poverty and inequality. Far from it.

De dios et al. observed that the “[…]main characteristics distinguishing the Marcos years from other periods of our history has been the trend towards the concentration of power in the hands of the government, and the use of governmental functions to dispense economic privileges to some small factions in the private sector.”

As regards the much vaunted infrastructure spending during those years, they further added that “[…]the bulk of construction and other capital outlays in both the private and public sectors were not very productive and many were outrightly wasteful.”

And in lieu of a strong developmental rationale, they further observed that “[…]a more urgent reason for pursuing them was the opportunity to use government activity as a vehicle for private gain, whether pecuniary or political. Examples would be overdesigned bridges, highways, public buildings or large energy projects designed to secure a political constituency, to get a commission, or to corner a contract.”

White elephants

There are few more palpable and glaring examples of the economic mismanagement of the time than the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) located in Morong, Bataan. Started in the 1970s, the BNPP was supposed to boost the country’s competitiveness by providing affordable electricity to fuel industrialization and job creation in the country. Far from this, the US$2.3 billion nuclear plant suffered from cost over-runs and engineering and structural issues which eventually led to its mothballing—without generating a single watt of electricity.

Corruption charges were later filed by the Presidential Commission on Good Government against Marcos crony, Herminio Disini, whose wife is the first cousin of first lady Imelda Marcos, and whose firm served to usher the BNPP deal. Westinghouse, the US company that supplied the BNPP, later testified in a US court that they paid Disini over US$17 million to help acquire insurance, telecommunications and civil works subcontracts for the BNPP without competitive bidding. Disini’s cousin, Jesus Disini, also admitted to the same court that President Marcos himself received part of this pay-off because he was co-owner of the group of companies headed by Herminio Disini. Until today, the BNPP case remains unresolved. (READ: Search for Marcos wealth: Compromising with Marcos cronies)

At its peak, the debt payments for the BNPP reached, on average, US$150,000 per day. The country finally paid the debt for the BNPP in 2007. The resources funnelled into this project could have funded over 40,000 classrooms to educate almost 2 million Filipino children, or three squadrons of FA-50 aircraft to help defend Philippine sovereignty, or account for half the cost of a high speed rail connecting Clark and Manila. This single corruption-laden project alone robbed the country of these worthier investments.

Worse yet, the rent-seeking and corrupt environment that produced the BNPP and many other white elephant projects during those times signalled an erosion of many key institutions that would take decades to recover.

Post-Marcos economy

The very things that signal the Philippine economy’s competitiveness today – an independent central bank, an effective fiscal and treasury management system, strong checks-and-balances built into public procurement and public-private-partnership (PPP) tenders, increased competition introduced to once-monopolized economic sectors, stronger oversight over government owned and controlled corporations (GOCCs), among many others – are among the very areas that differentiate the Philippine economy today with the Marcos-era economy.

Yet, persistent poverty and high inequality, along with the rise of many “mini-dictatorships” by political families across the archipelago provide a strong reminder that much work still needs to be done.

And no single president or administration has the political capital to put together all the reforms all at once. One can quibble about how many more reforms this or that administration should have been able to put in place, or could take credit for having achieved them.

In truth, all good economic outcomes are produced and sustained by many presidents. Yet one thing is clear: a government that went about undermining the very foundations for growth, development and democracy should be easy to spot.

To call the Marcos economy superior to our economy today simply flies in the face of economic history and empirical evidence. Returning the reins of power to a dictator (or to leaders who belittle the damage caused by dictators like Marcos) in order to somehow hasten economic and political reforms? That would be the greatest irony of them all. – Rappler.com

The author is an economist and a martial law baby. He thanks Jerome Abesamis, Edsel Beja, Monica Melchor, Dave Timbermann and Benjie Tolosa for their inputs and advice on this article.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.