SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

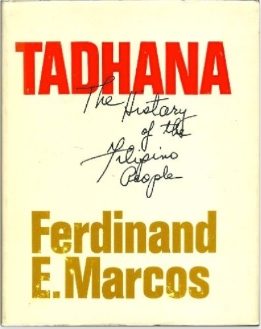

In 1987 while walking around Avenida, I stumbled upon Tadhana. No, this was not the DVD version of today’s teen flick, That Thing Called Tadhana, starring Angelica Panganiban and JM de Guzman. This was the book Tadhana: The History of the Filipino People, penned by former president Ferdinand Marcos, and put out by the Marcos Foundation.

I found two volumes at a stall selling used books, thrust at the bottom of a book stack full of Mills and Boon novels. The vendor I bought the books from (P25 per hard bound copy) said these were part of the loot that was taken out of Malacañang when the dictator was ousted from power on February 25, 1986.

“Destiny” was a project of the Marcos dictatorship. Its goal was to write a new history of the Filipino people dating from as far back as ca. 300 million BCE to the “present” (1986?). Only 3 volumes were completed.

These were Part 1 (published only in 1980!), which is a substantive examination of the “archipelagic genesis” of the islands “pre-historic” beginnings of the archipelago; Volume 1 (1976): Devoted to the evolution of the Philippine “Island World”; Volume 2, Part 1 (1977): Covers the world in the 16th century to the “early encounters” between Spanish and the people of the islands; and Volume 2, Part 3: Runs from the Philippines “in an Age of Ferment” to the “Politics of Religion” under Spanish rule.

In 1976, a more compressed “volume” also came out with the title Tadhana: The Formation of the National Community (1565-1896).

The mishmash of Destiny’s dates of publication is not our concern at this moment. What is more germane here is to determine why Marcos “wrote” the books, and how the writing came about. The “author” never explicitly laid out Destiny’s rationale but it is safe to assume that the project was part the effort of “that martial law thingy” to prop up its legitimacy.

‘Hackneyed excuse’

What was most interesting was Destiny’s authorship. While Marcos’ name is embossed on the volumes’ cover, in reality, it was a group of historians from the University of the Philippines that Marcos contracted (and offered hefty honoraria) to comb the archives for primary data, and write the texts.

Marcos would read the drafts, and if he approved them, they got published not under the name of its real authors, but under that of the dictator.

This issue came to light again, for me, as I got puzzled over the difficulties anti-Marcos forces faced in trying to oppose the efforts of Bongbong Marcos and his followers to distort history. Bongbong’s armor hardly dented, thanks in part to a professional PR machine he allowed to push back. And as icing on the cake, he often glibly invokes the overused phrase, “Let historians judge my father’s rule,” to silence his opponents.

It is this same hackneyed excuse that the historians used to explain why they willingly worked for the dictatorship. When criticized for being paid mercenaries of an autocratic regime, these historians have put up a vigorous defense, claiming that they took the blood money because of their love for the nation. Destiny may be a project aimed at legitimizing the dictatorship’s place in Philippine history, but it was also a worthy undertaking because it contributed to the quest for nationhood by tracing the pre-historic foundations on which the future nation would stand. To paraphrase Deng Xiaoping, it did not matter whether the Destiny was black or white, as long as it moved the “national History” forward. And only “History,” they claim, would judge whether what they did was mercenary or noble.

Contradiction

It is this defense (excuse?) of their product that also explains the difficulty in writing a systematic critique of those dark years of repression. For some of the country’s top historians of the country will not participate in any collective effort to enlighten our people about the dictatorship because they believed in what they did. Some even see no contradiction between their alleged progressive sentiments and working for the dictatorship; in fact they hint that the two actually complemented each other.

Take, for instance, Reynaldo Ileto’s April 5, 2016, lecture at Chiangmai University’s Center for ASEAN Studies conference on “Local Scholars in Southeast Asia” is illustrative (uploaded on YouTube).

In his intellectual talambuhay (biography), the author of Pasyon and Revolution explained his involvement in the Destiny project as something that he “had to do that because we were employed by the University of the Philippines….I was at the University of the Philippines History Department.” (25:27 minute; underscoring mine).

This formalist excuse (we work at the State University, so, part of our duty is to serve for the dictatorship) is not true. For despite the debilitating military repression, UP students and faculty fought back; some for political reasons – they were part of a rejuvenated communist underground network at UP – and others because they valued the State University’s long tradition of unrelenting defense of its autonomy and academic freedom.

True, there were professors and students who served Marcos or kept quiet. But there were also those who rose to the call of academic-activists like then Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Francisco Nemenzo to challenge the dictatorship, to not become mercenaries of Marcos, shun the offer of a higher pay, and thus live up to their role as mga Iskolar ng Bayang inaapi.

One outcome of UP students and faculty being true to their vocation was the first massive protest staged in 1977 against the dictatorship’s decision to increase tuition fees. A recently returned Ileto, now working at the UP Department of History, did not even seem to notice this historic event. Why?

One can attribute this benightedness about UP’s hallowed traditions to location – Ileto, after all, was an Atenista who only came to UP after graduate school. But to claim that he belonged to an older generation that was famous for its scholarship and its activism sounds out of synch with his contribution to writing the dictator’s history. During those polarized times, UP knew what being an activist was and was not. A newcomer, say like a smart Ateneo graduate, could have easily noticed how much UP folks value this distinction.

‘Creepy coldness’

The mystery behind this feigned unfamiliarity deepens when, in the 26th minute of his talk, Ileto rationalizes: “We had to kinda…maneuver ourselves between different forces.” But which forces was he referring to? Forces within the state that they were “obliged” to serve, or the forces within and outside UP that were fighting Marcos? Moreover, if this was the case, why “maneuver” inside the state?

The answer came 25 minutes later when Ileto suggests that historians should look into the involvement of scholars in the nationalist project. He argues that even if a leader of a country is a dictator, “the fact is history writing had to go on [where scholars] have to negotiate to limit state power if they want or enhance the state.” Ileto, however, did not push this argument to its logical conclusion.

His insistence that “history writing had to go on [and] scholars have to negotiate with state power” did not, in fact, limit state power. On the contrary, the research led to the production of knowledge establishing the historical foundations of a process whose acme is the national Utopia called the New Society. It was only because Marcos pulled the plug on the Destiny project in 1978 that prevented this historical revisionism from becoming a reality.

No way in Hell were these historians fighting (maneuvering against?) the regime. They were excusing it.

Finally, there is a creepy coldness to this position. A historian, according to Ileto, must continue with the task of “history writing” and be oblivious to the repression that is going on outside his cubicle or research desk. He must not be distracted by the torture, the massacres, the theft going on under “a leader of a country [who] is a dictator.” The idea of the “ivory tower” intellectual is pushed here to its most reactionary form, but also made more hideous because it comes from the imagination of one who proudly identifies with an “activist” generation.

Ileto’s talk is the 2016 edition of a topic that he has repeatedly raised since 2003. We can, therefore, assume that he still sees nothing wrong with the Destiny project. The consequences of this consistent position can be fatal. Those wanting to write the real story of martial law will not have Ileto’s “activist generation” on their side. And, to add insult to injury, younger scholars are doubly incapable of doing this project because they are – as Ileto dismissively puts it in the video – “not interested in politics and the world” in the first place.

This is, of course, another spurious and insulting claim. Young scholars have fought against the legatees of the Marcos dictatorship and they continue to oppose the conservative state the same way their elders had done.

What is significant in this last statement is that it is a warning that no help will come, not even from someone who claims to “write history from below” and give peasants their voice, but forgets to mention that a large part of that voice is targeted at the oppression of the national state in the name of popular democracy. – Rappler.com

Patricio N. Abinales is an OFW.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.