SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION] Higher inflation: Is TRAIN to blame? (Part 2)](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/9178AD3B3FD742269B597E8AE62D25AC/train-inflation-part-2.jpg)

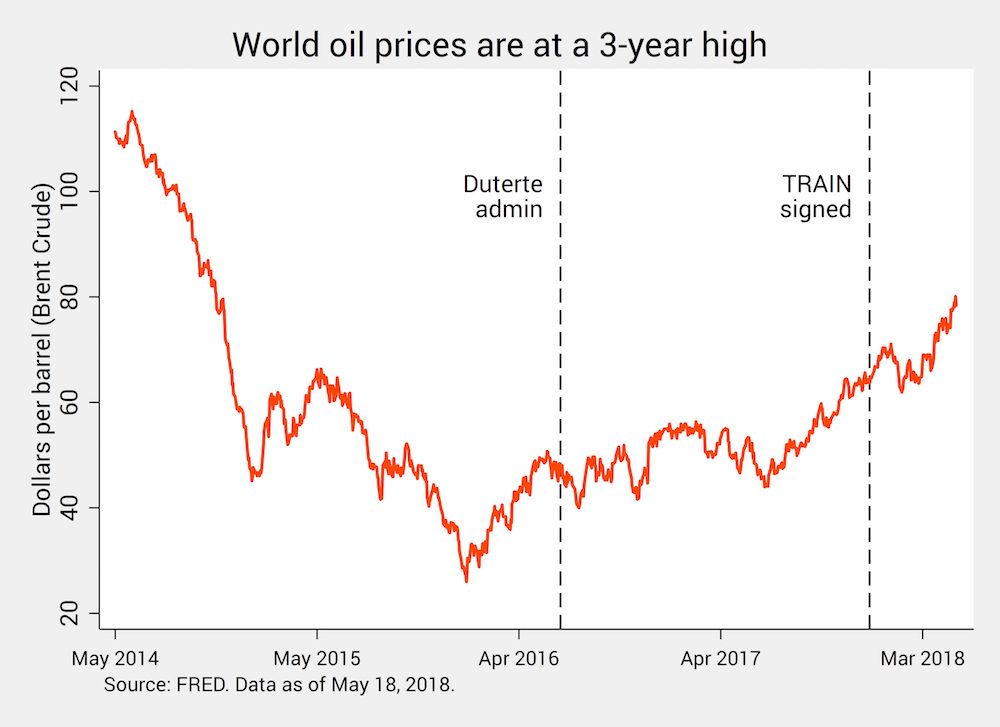

In Part 1, I explained the international factors behind the recent rise in inflation: a surge in world oil prices (now at a 3-year high) and the weaker peso (now at a 12-year low).

In Part 2, I focus on TRAIN and why its timing is bad. I also explore the policies government can and cannot pursue to cushion the impact of higher inflation on Filipinos.

TRAIN’s role

TRAIN’s contribution to the recent acceleration of prices is threefold:

First, it directly increased the prices of certain products – like petroleum, automobiles, and sugar-sweetened beverages – owing to its new excise taxes.

Second, the impact of these new excise taxes has rippled across the economy, raising inflation across the board.

Third, opportunistic businessmen have used TRAIN as an excuse to charge unwarranted price increases and reap above-normal profits.

In a time of high world oil prices and a weaker peso, it’s clear that TRAIN arrived at a most inopportune time. But just how large are its contributions to inflation?

Recently, the Department of Finance (DOF) published a breakdown of the factors behind the excess inflation seen in April 2018. With inflation at 4.5% and the Bangko Sentral’s target at 3%, excess inflation then amounted to 1.5 percentage points.

Of this, the DOF claims only 0.4 percentage point (or 26.7%) was due to TRAIN’s excise taxes and the higher inflation it caused.

But, more tellingly, 0.7 percentage point (or 46.7%) was due to “other factors (notably profiteering).”

Back in January, a number of gas stations were reportedly applying the new excise taxes on old inventories of gas and diesel, even if the law was supposed to apply to new stocks.

To learn that, months later, profiteering could still be a major contributor to inflation is quite disturbing. It raises a number of questions: How many businesses are abusing TRAIN to charge unwarranted price hikes? What mechanisms are in place to monitor prices and ensure that profiteers are caught and charged accordingly? Is government going after these profiteers hard enough?

It’s not clear what the “other factors” are besides profiteering. But assuming that all (or most) of the 0.7 percentage point was due to profiteering, then the combined impact of TRAIN on higher inflation is, in fact, a total of 1.1 percentage points, or 73% of the excess inflation in April 2018.

Does this mean that TRAIN could be responsible for much of the excess inflation we’ve seen in recent months – even more than the surge in world oil prices and the weaker peso?

Does this also mean that the economic managers are misleading the public by constantly trumpeting that TRAIN is responsible for just 0.4 percentage point of the 4.5% inflation in April?

What can government do?

With higher inflation thrust upon us by both international and local factors, what can government do to minimize its impact?

On May 10, 2018, in a bid to temper inflation, the Bangko Sentral raised its benchmark interest rate from 3% to 3.25% – the first interest rate hike since September 2014.

The idea is to induce households to save more and consume less in the short run, reducing overall demand in the economy and preventing prices from rising further.

Such an interest rate hike works best if inflation is caused by demand-side factors. But, as we’ve noted, higher inflation now is overwhelmingly caused by supply-side factors like higher world oil prices, a weaker peso, and profiteering.

Another way to fight inflation is by “tariffying” rice import quotas, or converting them into their equivalent tariffs. NEDA estimates that a 35% tariff on rice could reduce the price of rice by P4.30 per kilo, so that each family could save as much as P2,362 per year.

Meanwhile, the TRAIN law itself provides for palliative cash transfers to the country’s poorest families – worth P2,400 per family in 2018, and P3,600 per family in 2019.

But this amount may prove insufficient because it’s fixed regardless of how many kids there are in a poor family, and regardless of how high inflation is. (READ: Without enough transfers, tax reform law will hurt the poor)

Logistical nightmares – like the need to verify the identities of millions of poor people – also delay the disbursement of such transfers. Hence, some families might not receive aid until August or September, several months after the initial surge of inflation brought on by TRAIN.

Financial aid to jeepney drivers, called Pantawid Pasada, will also not come until later this year because bureaucrats are still scrambling to assemble the database of beneficiaries.

Should we stop TRAIN?

Higher inflation, coupled with the forthcoming 2019 midterm election, has suddenly turned TRAIN into a political hot potato.

At least 3 senators – all of whom voted for TRAIN – are now calling for its suspension. One senator even claims he didn’t get to read TRAIN’s final version, and that he voted for it with a “critical yes bordering on a no” (whatever that means).

Other lawmakers, meanwhile, are toying with the idea of granting a nationwide minimum wage hike to P800 per day, as petitioned by certain labor groups. To see how large this is, the current minimum wage rate in Metro Manila is just P512.

Lawmakers will do well to steer clear of their populist instincts lest they make things even worse.

Though it may be too late to stop TRAIN as a whole, lawmakers could still put the brakes on its petroleum excise taxes.

Not many people know, however, that TRAIN actually contains a circuit breaker in case oil prices go awry. Petroleum excise taxes are actually set to increase in 2019 and 2020. But TRAIN provides that if the benchmark called Dubai Crude reaches $80 per barrel, these higher taxes will not kick in.

Even with such a provision, the law provides that the initial wave of petroleum excise taxes is here to stay no matter what.

Who’s to blame for TRAIN’s painful petroleum excise taxes?

TRAIN’s proponents now admit that, when they crafted the law as early as mid-2016, they failed to anticipate the extraordinary rise of oil prices we see today. They also likely failed to incorporate in their calculations the profiteering that TRAIN would inspire.

Ultimately, however, responsibility for TRAIN lies with the lawmakers who passed it. Figure 1 shows that, in the months leading to TRAIN’s passage, world oil prices were already picking up.

In other words, lawmakers had every opportunity to modify TRAIN and introduce provisions that could further soften its blow. They have no one to blame for the law’s inadequacies other than themselves.

Meanwhile, allowing a huge minimum wage hike could result in a so-called “wage-price spiral.”

That is, if workers successfully lobby for a huge wage increase, additional demand across the economy could stoke inflation and prompt a new round of wage hike requests, resulting in yet higher demand, higher inflation, etc. (Remember that the Bangko Sentral is fighting inflation by nudging people to spend less, not more, in the short run.)

Worse, a wage-price spiral could force the Bangko Sentral to raise interest rates further, and this could eventually put a damper on overall economic growth.

No one denies that our people need economic support now because of extraordinarily high inflation which might not go away any time soon.

But the tradeoff should be clear to policymakers: if we want to provide workers with more relief now – in the form of higher minimum wages – we should not be surprised if inflation persists in the future. Because of this, temporary unconditional cash transfers might be the more prudent course to take now.

Needless to say, this is a delicate balancing act that lawmakers must tread carefully lest prices could easily spin out of control.

Don’t belittle the poor

All in all, tempering inflation is no mean feat, and government may find it difficult to balance all the economic and political tradeoffs at play.

As we ride out this episode of unusually high inflation, the least government can do is to show some sympathy for the economic worries besetting millions of Filipinos.

But even here Duterte’s economic managers can’t seem to deliver. One callously said, “Let’s just tighten our belts.” Another said, “We should be less of a crybaby.”

By belittling the poor and brushing aside their worries – especially in a time of acute economic hardship – Duterte’s economic managers betray their lack of genuine interest to serve the people.

Until the economic managers check their privilege, filter their words, and show genuine empathy, they also can’t expect many Filipinos to support and rally behind their pet projects and policies, no matter how crucial or well-crafted they are. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter: @jcpunongbayan.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.