SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Why the free tuition law is not pro-poor enough](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/076D323D11124CC5891DAFBB5A2180BD/img/D764DDAA3E844E788A7C86594E1F4652/Why-the-free-tuition-law-is-not-pro-poor-enough--Feb-8-2019.jpg)

Improving the poor’s access to quality tertiary education is far from being a done deal.

The free tuition law (Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act) signed by President Duterte in August 2017 subsidizes the tuition of all students in public higher educational institutions (HEIs).

Public HEIs include state universities and colleges (SUCs), local universities and colleges (LUCs), and technical-vocation education and training (TVET) programs.

While the free tuition law was lauded as “pro-poor,” a deeper examination shows that it is not. It’s even demonstrably pro-rich.

In this article we review the economics of the free tuition law and explain why it’s not as pro-poor as it seems. We also discuss ways by which we can make it work better for the poor.

Who benefits?

The law is not so equitable for two main reasons.

First, a lot of its subsidies accrue to the non-poor rather than the poor.

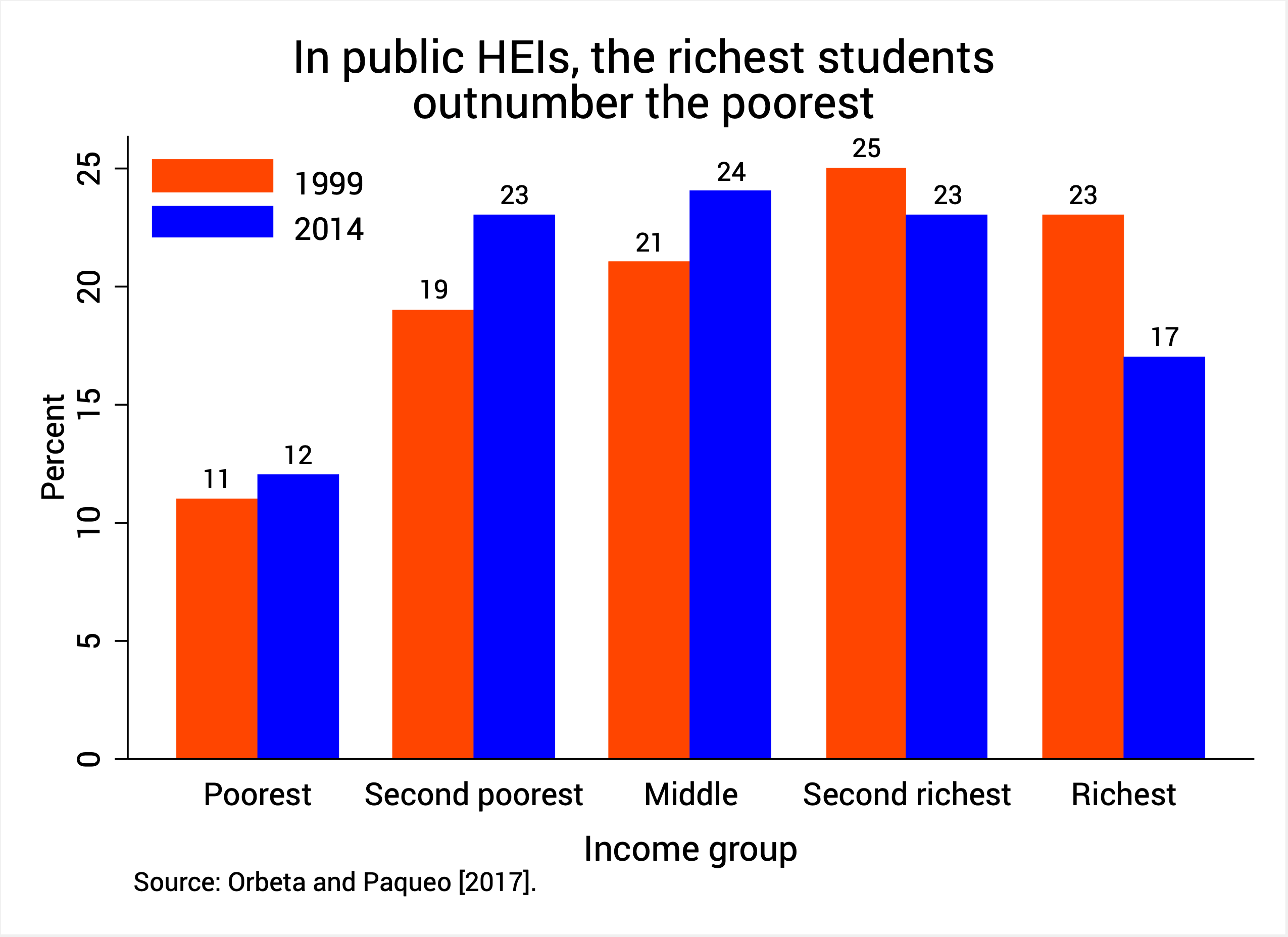

Figure 1 shows that as much as 17% of public HEI students (or 4 out of 10) came from the richest fifth the population as of 2014. In contrast, only 12% came from the poorest fifth. The same pattern was observed back in 1999, and was even worse.

This implies that the free tuition law involves giving considerable sums of money to rich students whose parents are otherwise capable (and very much willing) to pay for their children’s public tertiary education.

With a P40-billion budget last year, this is tantamount to writing a P7-billion check to students belonging to the richest fifth of the population.

Figure 1

Figure 1

There are many reasons for this overrepresentation of the rich in public HEIs.

For example, admissions policies tend to be biased toward the rich, richer students have easier access to tutors and other resources in basic education, and review centers are more affordable for them, too.

It’s therefore no surprise to see that richer students are much likelier to proceed to tertiary education (and graduate) than their poorer counterparts (see Figure 2).

Hence, if we want more poor students to benefit from public tertiary education, a free tuition policy, by itself, clearly won’t suffice. (READ: Free tuition alone won’t make college any more accessible)

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Second, the free tuition law is also not so equitable because its costs are borne mainly by poor and middle-class Filipinos.

Who pays?

Data show that as much as 80% of income taxes in the Philippines are paid for by workers who earn wages and salaries. Only 20% are paid for by professionals and the self-employed, people who don’t only earn higher incomes on average but also find ways to hide part of that from the authorities.

The TRAIN Law (Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion) promised to remedy this by placing a heavy tax burden on the richest members of our society.

But another study said that TRAIN might fail to do so. For instance, we saw last year that TRAIN’s excise taxes on petroleum products, sugar-sweetened beverages, and other goods hurt the incomes of the poor the most via higher inflation (inflation is like another tax on people’s incomes).

In addition, the simplified payment scheme for estate and donor’s taxes also likely benefitted a lot of the elite.

So, all in all, not only do the poor and middle class pay for a bulk of the country’s income taxes, but the free tuition law’s subsidies also disproportionately benefit the rich. In this sense, the free tuition law can be seen as a reverse Robin Hood scheme.

Some people argue that we can give subsidies to both rich and poor students if only Congress allocated more money for these subsidies. But remember that it’s the Filipino taxpayer who ultimately pays for these sums, and right now the rich are not paying for their fair share.

Instead of the poor paying for the tuition of the rich, should we not push for the opposite?

What can we do?

How then can we make public HEIs more accessible to the poor?

- We can push for tax reform measures that go after the incomes of the rich more aggressively. In other words, we need to see a much more “progressive” tax system than what we currently have.

- Some economists have proposed that government can bolster programs that target subsidies to the poor.

Not many people are aware, for example, of the UniFAST program (Unified Student Financial Assistance System for Tertiary Education), which consolidates all forms of government scholarships and financial assistance for tertiary students under one roof.

UniFAST relies on the government’s comprehensive database of the poor, otherwise known as Listahanan. Through this, it’s much easier to identify and transfer money to poor students unlike your typical scholarship or student loan program.

To see the superiority of targeted subsidies in general, consider the following back-of-the-envelope calculation.

Right now Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno estimates that the budget of the free tuition law in 2019 will be P51 billion. Assuming there are around 1.5 million students in public HEIs, this means each student will get P34,000 this year.

But say we let the richest 20% of students pay for their own tuition, so we only have to cover 1.2 million students. Then with the same P51-billion budget – financed by taxpayers in the end – we can now give as much as P42,500 to each student.

For each of those 1.2 million students, this translates to 25% more subsidies which they can spend not only on tuition but also on living allowances and miscellaneous expenses.

In sum, a targeted scheme does not at all get rid of the subsidies to poor students. Instead, by making the rich pay (since they can and will), we free up even more subsidies to aid poor students most in need.

Room for improvement

The free tuition law is here to stay. Any politician who dares question it (or propose its repeal) will be committing political suicide.

But this should not stop us from seeking ways to improve the law and help it achieve its avowed objective of making tertiary education accessible to as many Filipinos, especially the poor.

Along with this, I think we must simultaneously confront the deep-seated inequities in our basic education system.

But how can we do this if this year the Department of Education is actually facing its largest budget cut in years, to the tune of P51 billion?

We cannot truly reform the higher education sector without also reforming the rest of the education sector.

Is the current leadership up to this task? Are they paying enough attention to the education sector? – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Thanks to friends for valuable comments and suggestions. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.