SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] How the Philippines fell for China’s infamous debt trap](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/4A28195AED624C8C822AD8D3349B6715/img/F033F7A2FDAE4B8595B2A0395D94F4C1/china-debt-trap-carousel.jpg)

China’s debt trap was completely avoidable. Yet we still fell for it.

No less than Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio of the Supreme Court has combed through the Chinese loan agreements entered into by the Duterte administration and found onerous provisions that imperil our nation’s “patrimonial assets.”

That China is capable of imposing such conditions should come as no surprise.

China, in its bid for global economic and political dominance, has wantonly trampled on the rights and sovereignty of many a developing country.

But how exactly does China’s debt trap work? How deep are Filipinos into this mess? And who must be held accountable?

Onerous provisions

It was only recently – after much public pressure – that the Department of Finance (DOF) published on its website the full text of the loan agreements recently entered into by the Philippine government.

Justice Carpio zeroed in on the loan agreement for the Chico River Pump Irrigation project and pointed to 3 onerous provisions:

First, the Philippines apparently agreed to waive its sovereign rights on “patrimonial assets” or properties owned by the state not “intended for some public service or for the development of the national wealth.”

Carpio claimed that Reed Bank – along with its estimated 5.4 billion barrels of oil and 55.1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas – is in danger since a 1972 law had already declared such resources as patrimonial.

Second, in the event of a dispute about this loan, the Philippines also agreed to subject itself to an arbitration to be held in Beijing, overseen by a tribunal that will always be composed by a majority of Chinese nationals – thus putting us at a disadvantage by default.

Third, the loan agreement also stipulates that its details are to be held in “strict confidentiality,” in direct contravention of the 1987 Constitution.

Debt-trap diplomacy

These provisions are characteristic of loan agreements handed out by China across the world under President Xi Jinping’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative or BRI. (READ: What scares me the most about China’s new, ‘friendly’ loans)

Here’s how China’s infamous debt trap works:

- First, China offers to build and finance infrastructure projects in a developing country even if such projects have low expected returns or are wholly unfeasible.

- Second, the borrower-country, often small and poor, finds itself unable to pay.

- Third, China collects as collateral the borrower-country’s natural resources or strategic assets.

One famous example is Sri Lanka: after failing to repay China for the construction of the $1-billion Hambantota Port, the Sri Lankan government was forced to lease the said port to the Chinese for the next 99 years.

Another example is Ecuador: China built near an active volcano the $1.68-billion Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric dam, and Ecuador repays its loans by giving up 80% of its oil resources to China.

Many other countries are in peril.

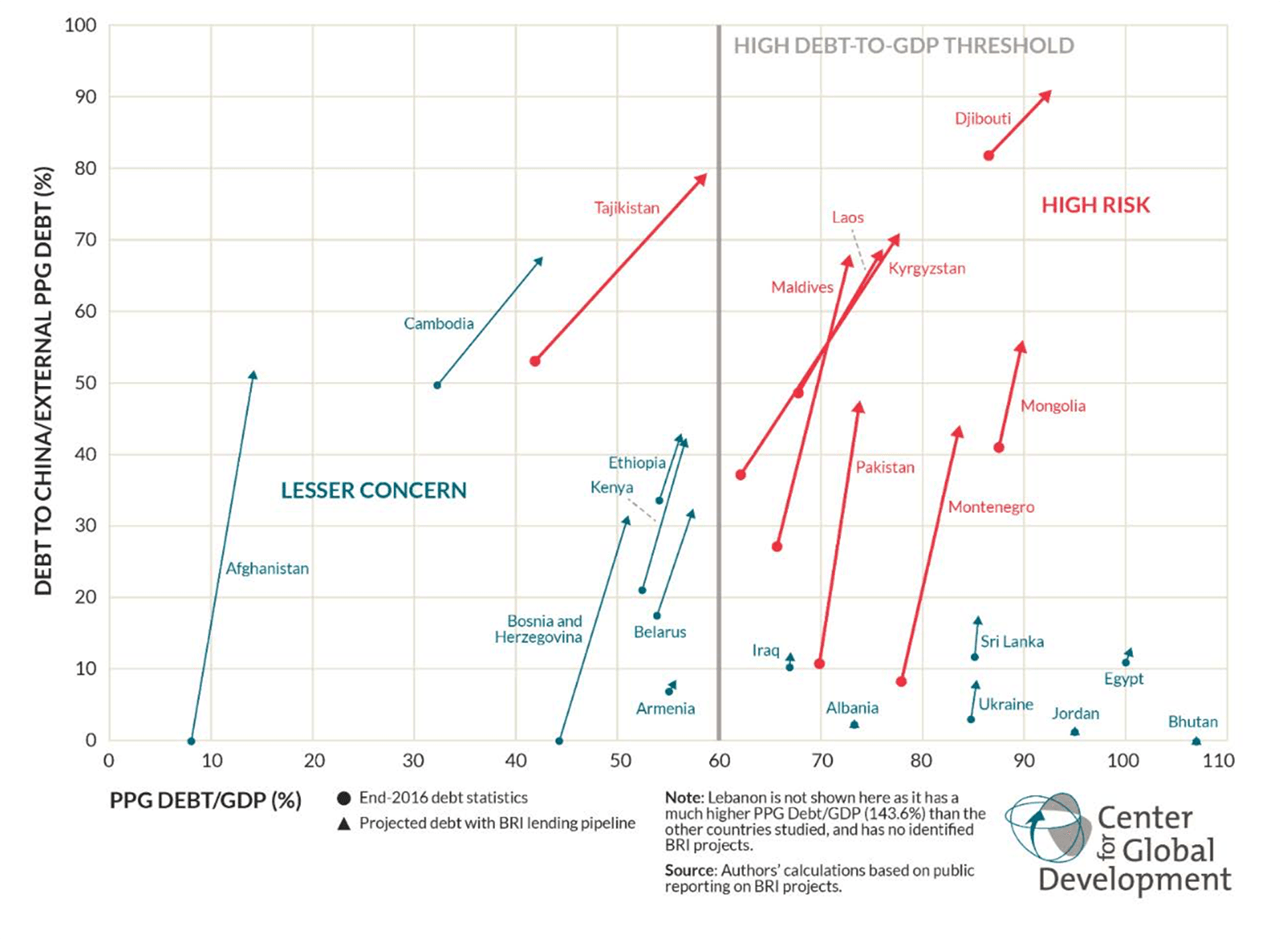

A 2018 study by the Center for Global Development found 8 countries at high risk of defaulting on their new Chinese loans: Pakistan, Djibouti, Maldives, Laos, Mongolia, Montenegro, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan.

Figure 1 shows that not only do these countries have dangerously high levels of external debt to begin with, but the share of debt they owe to the Chinese is also projected to jump tremendously in the coming years.

Pakistan, for example, incurred a whopping $50-billion additional debt from China under BRI, slapped with high interest rates. Meanwhile, in Laos, one BRI project (the China-Laos Railway) costs $6.7 billion or about half the size of Laos’ national output.

Figure 1. Note: Countries with red arrows are at a high risk of default.

Imprudent management

Thankfully, the Philippines is not remotely at risk of defaulting on its new Chinese loans – yet.

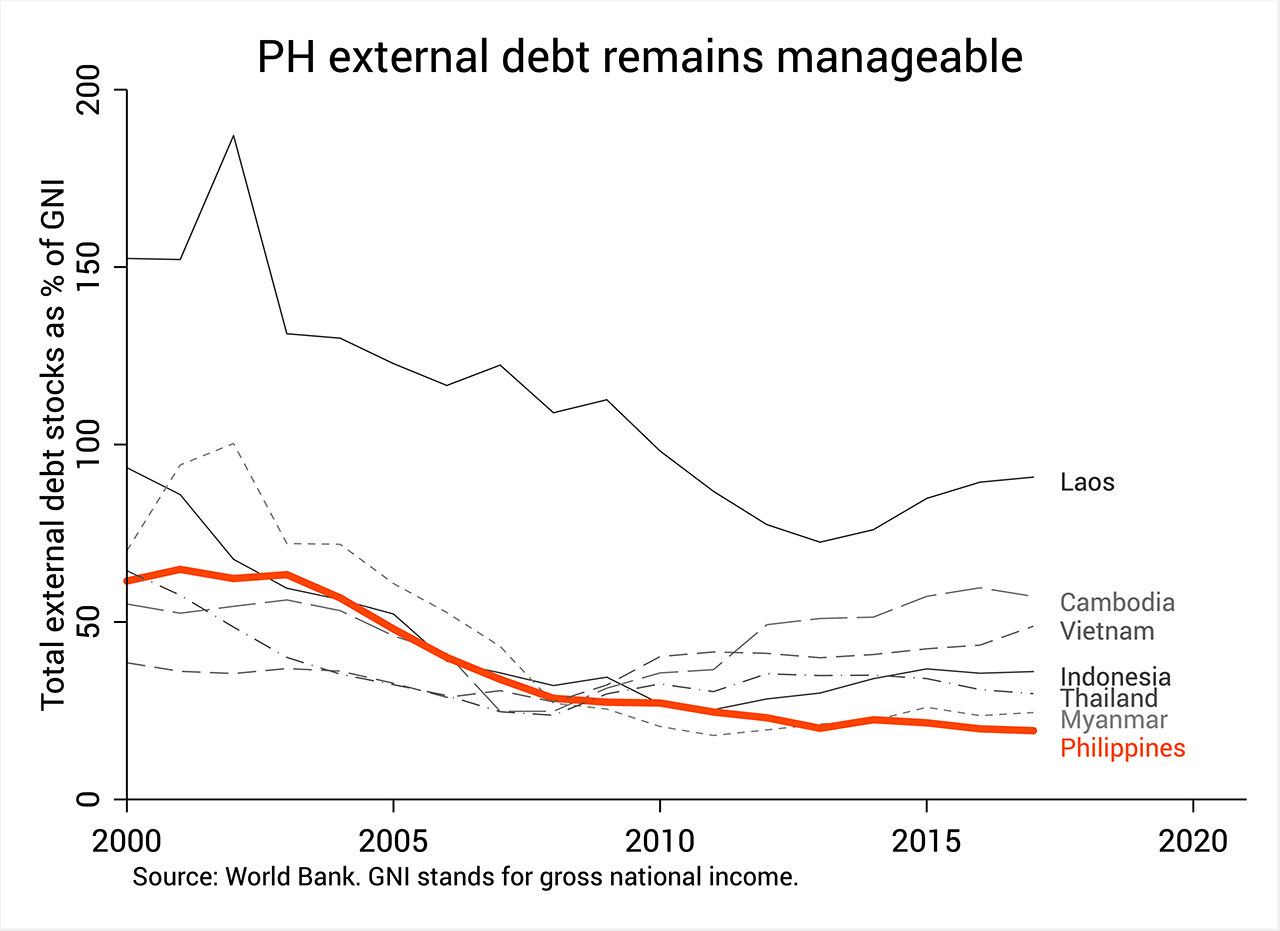

As of 2017 the Philippines’ debt-to-GNI ratio – which pits the country’s debt against the size of our national income – was recorded at just 19.4%. Figure 2 shows that it’s in fact the lowest in ASEAN.

Our debt-to-GNI ratio has also dropped significantly since its peak in the mid-1980s, when it reached 99% (back then our external debt was almost as large as our economy).

Figure 2.

The amounts we borrowed from China so far are also not terribly large.

The Chico River Pump Irrigation project costs P4.7 billion, while the Kaliwa Dam project costs P12.2 billion. By contrast, the Japanese-funded Metro Manila Subway and North-South Commuter Railway Extension projects cost P357 billion and P628 billion, respectively.

This is not to say, of course, that there is no cause for concern.

To ably repay our loans we must ensure that our economy’s growth (as measured by GDP growth) remains robust.

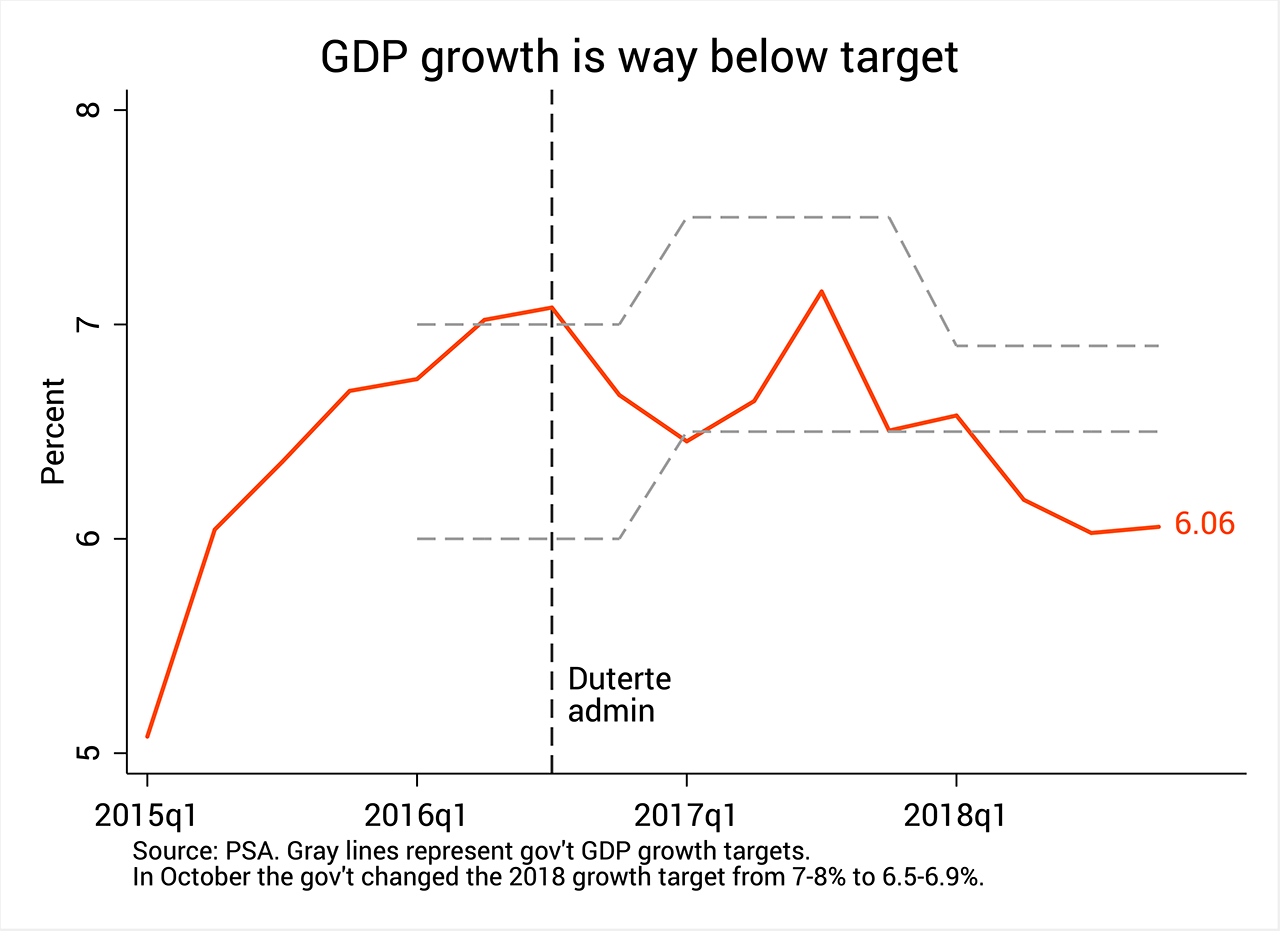

But latest data show that GDP growth clocked in at just 6.1% in the last quarter of 2018, lower than the government’s target, and lower than the 7.2% growth rate that Duterte started with in 2016.

Unfortunately, growth might only falter further.

Failure to sign into law the 2019 budget, for example, could stall important projects like Duterte’s infrastructure push called Build, Build, Build.

The economic managers themselves conceded that GDP growth might drop to a mere 4.9% if the reenacted budget lasts until August, or even to 4.2%, if the 2019 budget is not signed into law.

In this time of wobbly growth, continuing to enter into patently onerous loan agreements could qualify as imprudent economic management.

Figure 3.

Learn to say no

It strikes me as hypocritical that Duterte wishes to arrest without warrant (even kill) “5-6” lenders for their supposedly onerous loans. Yet Duterte himself fell for China’s debt trap – hook, line, and sinker – and in the process put at risk the country’s natural resources and strategic assets.

For this betrayal of public trust, heads must roll.

Manageable debt is no excuse for government to indiscriminately sign demonstrably onerous Chinese loan agreements. It’s the Filipino people who will ultimately repay such loans, and prudence dictates that government should avoid them.

But our officials will have to learn to say no to China.

Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad shows us a way forward: in his latest visit to China he bravely announced that Malaysia will be shelving 3 China-backed projects.

He said, “I believe China itself does not want to see Malaysia become a bankrupt country.” He even branded China’s BRI as a form of “neocolonialism.”

Mahathir’s example should inspire small countries seeking to stand up to China’s economic and political bullying.

Will Duterte do a Mahathir? I doubt it. But more than ever, we need a leader who will. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.