SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Is Canada becoming anti-immigrant?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/r3-assets/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/3DAF2D171739413F83B6EA88121908D3/analysis-is-canada-becoming-anti-immigrant-august-23-2019.jpg)

“Go home.”

He mouthed the words and kept walking.

I typically greet seniors I encounter on my way to work with a “Good morning,” and I did so one crisp, fall day when I saw a white old veteran in uniform, presumably on his way to attend a Remembrance Day commemoration. When he hurled the racial slur it happened so swiftly, so unexpectedly that it left me dumbfounded.

I was reminded of this incident, which happened 3 years ago, as I noted a rise in news reports about people of color in Canada, especially hijab-wearing or niqab-wearing Muslims, being accosted in public places and told to “go back to where you came from.”

At least 6 polls conducted so far this year have indicated that the attitudes of Canadians toward immigrants, migrants, refugees, and asylum-seekers are changing. The words that news media and pundits have used to describe this range from being “nervous” to a “hardening of public opinion” about immigration. Canada welcomes about 300,000 immigrants every year, and Ottawa wants to increase the number to 350,000 by 2021.

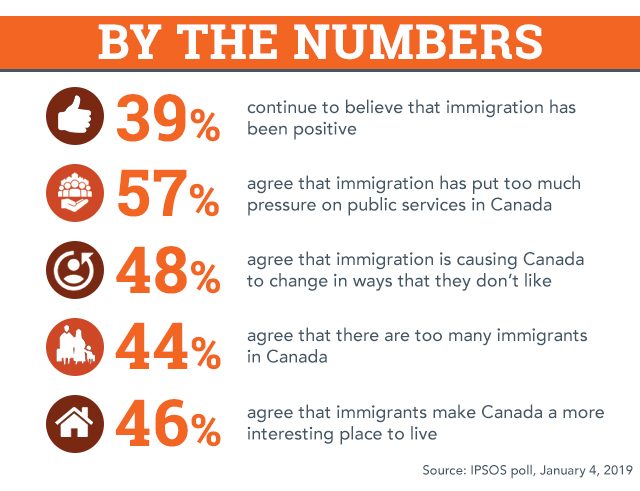

In January, an Ipsos poll showed that 4 in 10 Canadians believe the country now has “too many immigrants,” and 57% say immigration has “placed too much pressure on public services.” Forty-eight percent agree that “immigration is causing Canada to change in ways they don’t like,” and 54% say the country is accepting too many immigrants.

Change in attitudes

A Leger poll conducted in June for Canadian Press said 63% of respondents believe the government “should limit immigration levels because the country might be reaching a limit in its ability to integrate immigrants.” The same poll shows that Conservative voters are “far more likely to favor limiting immigration,” with 81% expressing this view, compared to only 41% among Liberals.

The change in attitudes, compared to a decade ago, is hardly surprising. The refugee and migrant “crisis” in Europe, which exploded in 2015, and the 2016 election of Donald Trump have had ripple effects over Canada. Between 2015 to 2017, in response to the unprecedented humanitarian crisis in the Middle East, Canada welcomed 50,000 Syrian refugees and not everyone was happy about it. Trump’s harsh immigration policy has resulted in an about 43,000 irregular border crossings to Canada from the US since 2017.

Canada has not been immune to the rise of far-right and neo-Nazi ideology in Europe and the US. There are at least 130 active far-right extremist groups across Canada, a 30% increase since 2015, says hate crime expert Barbara Perry in a CBC documentary. “Most of these groups are organized around ideologies against certain religions and races, with anti-Muslim and anti-Jewish sentiments being the most common, followed by hatred for immigrants, indigenous people, women, LGBTQ communities and other minority groups,” said Perry.

So is Canada heading towards the same path as the US and Europe? Not entirely, say experts and journalists, but there are warning signs.

“When it comes to immigrants and refugees, Canadians in general tend to be a lot less excitable or inclined to racism than is convenient to certain strangely popular narratives at the moment,” writes respected columnist Terry Glavin, in an article for Maclean’s. “At the fringes, hate crimes are up, and white-nationalist delirium is becoming fashionable among a creepy subset of far-right and friendless unemployable young men. It would be easy to misread the public mood. But the public mood is not taking any dramatic turns for the worse.”

Still, Glavin notes an observation made by Frank Graves, president of EKOS Research Associates, that “something new and alarming is definitely happening in Canadian public opinion” towards immigration. EKOS has been tracking Canadian attitudes about immigration since the 1990s.

“What is extremely important is to note that opposition to immigration in general – and visible minority immigration in particular – is not up dramatically. What is dramatic is the level of ideological and partisan polarization on this issue,” EKOS said in its release of poll data in April. Attitudes toward immigration “have become much more polarized and our research suggests that they are sorting voter choices in ways that we have never seen before in Canada.”

Minority newcomers

What is new, Graves also told Huffington Post is that the poll suggests a reluctance to welcome visible minority newcomers. “It’s a pretty clear measure of racial discrimination,” Graves said. “A sizeable portion of Canadians are using race as something that would alter their view of whether or not there’s too few or too many immigrants coming to the country.”

“The reason this is so dangerous is that the conflation of immigration policy with race is threatening to determine the way Canadians vote,” writes Glavin. “It doesn’t matter which party benefits from this in the short run. It’s bad news all round. It’s the marker of what could be a descent into the same debilitating authoritarian-populist abyss into which the United States and much of Europe has fallen…. The inevitable result is a partisan polarization into two irreconcilable camps.”

Equally bad, writes Glavin, is “a tendency among Liberals and the liberal-left generally to conflate genuine concerns people might have about refugees, or about how Canada’s demographics are changing, with the crudest xenophobia and the lowest types of racism.”

To call people out as Nazis or racists, “and painting large portions of the population with this kind of inflammatory language, it’s really not helping. It makes things worse,” notes Graves.

EKOS notes that “ Immigration can be a difficult discussion to have in a nation of immigrants, and many appear to think that political correctness can get in the way of that discussion.” But a significant number (38%) agree that “politicians, media outlets and others in Canada who have spoken out in opposition to immigration have been treated unfairly.”

A poll conducted for federal immigration officials show that even immigrants themselves are divided about immigration. Immigrants who have been in Canada for more than 20 years feel that there are too many immigrants now (27%) compared with those who have been here for less than 5 years (16%). The figure is even higher for third-generation Canadians, at 32%.

Graves’ observations also echo a warning made by Citizenship and Immigration Canada officials that a “tipping point” could undermine public support for welcoming immigrants if the issue was not approached with care. Canadian Press, which obtained the information through access-to-information law, said immigration officials noted polling data that showed support dropped when Canadians were informed of how many immigrants actually arrive each year.

“If the government wants to do more on immigration, managing public attitudes and paying close attention to the performance of settlement services would be key,” the internal briefing note stated. The document noted other circumstances that could color attitudes toward immigration, including attitudes in other countries, feelings of disenfranchisement flowing from economic downturns and globalization.

In addition to having dispassionate discussions about immigration and racism, debunking stereotypes from both sides, and addressing concerns raised by a significant segment of the population, one can add to the mix the need to learn from the experience of how European media covered the refugee and migrant “crisis.”

Several studies have shown that the European press played a central role in framing the arrival of refugees and migrants as a “crisis” for Europe. “Overall, new arrivals were seen as outsiders and different to Europeans: either as vulnerable outsiders or as dangerous outsiders,” noted a Council of Europe report. The voices of migrants and refugees were often invisible in the stories, with quotes coming mainly from government officials and experts.

The same has happened in Canada, as shown by a Ryerson University study, The Syrian Refugee Crisis in Canadian Media, which monitored for 9 months how the country’s top newspapers and TV stations covered the arrival of Syrian refugees.

Syrian refugees were often depicted as “vulnerable, desperate and in need of saving,” it noted. While the intent may have been to “show the depth of the humanitarian crisis,” they nonetheless “removed the agency and resilience of Syrian refugees.”

Assigning “neediness and passivity” to refugees while focusing on the generosity of Canadians, combined with low numbers of interviews with them, reflect how the Canadian media engaged in the process of “othering” Syrian refugees, the study said.

Articles about how refugees were welcomed were “touching” but failed to “explore the harsh realities of resettling in Canada,” it added. Stories that discussed barriers to resettlement often focused on language and culture, and not on structural barriers such as employment, housing and education.

In response to shortcomings made by the European media in covering migration, the Ethical Journalism Network released a 5-point guide for migration reporting that covers the following: Facts Not Bias, Know The Law, Show Humanity, Speak For All, and Challenge Hate.

These are guidelines that can be applied anywhere in the world, including Canada. – Rappler.com

Marites N. Sison is a freelance writer and editor based in Toronto. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram at @maritesnsison

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.