SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

With the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) recently releasing economic growth figures (of 5.4% for Q3), I am sure that some will once again comment that they are not feeling this growth, particularly since GDP growth has not been accompanied by increased incomes or increased employment.

The PSA also recently released last October 2014 its estimate of unemployment rate (6.0 percent), that is slightly lower than the corresponding figure (6.4 percent) a year earlier.

These statistics, though, only represent areas excluding Leyte since the PSA still finds it operationally challenging to conduct its regular household

surveys such as the Labor Force Survey in the Yolanda-devastated province.

In a previous article, I did point out that per capita income has actually increased for various segments of income distribution in nominal terms for the past few years, but at growth rates commensurate to inflation, and thus poverty rates have remained the same. This isn’t necessarily a fault of government, given that conditions are never the same, especially with climate change negating whatever plans and programs we have embarked on.

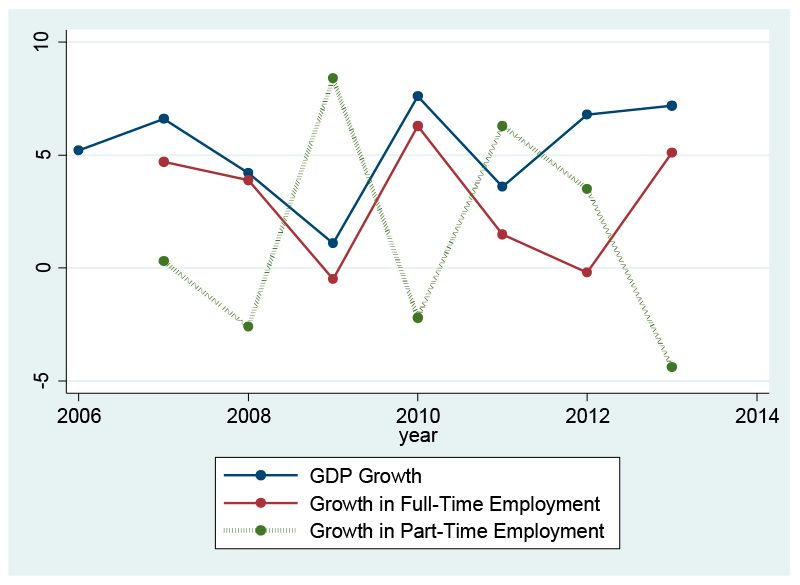

I thought it may be apt to re-emphasize a point I made about the myth of jobless growth that I already stated in a policy note at PIDS. As far as employment is concerned, people have rushed into examining employment growth and noticed the seeming divergence in growth of the economy and the growth in employment (Figure 1).

Population and growth

In recent years, it is clear that when the economy had high growth rates, the employment growth seemed to be rather low, such as in 2009. And when there was low GDP growth, there was a huge increase in employment. Thus, employment growth and GDP growth are negatively correlated.

In addition, the employment rate, i.e. the ratio of those in the labor force with employment activity in the past week, (as well as the unemployment rate) seem to have been unchanged, leading some analysts to characterize the economy as being jobless.

But a net change of zero for unemployment rates does not mean that there are no jobs being created since the population, including our labor force, continues to grow.

In the country, employment and unemployment data are regularly collected by the PSA in its quarterly Labor Force Survey (LFS). Disaggregating LFS employment data, however, debunks the myth of a “jobless growth” in the country. Increases in full-time employment (i.e., those who work 40 hours or more during the past week, the reference week in the Labor Force Survey) actually accompany high economic growth (except for 2012).

During economic slowdowns, full-time employment also goes down. As regards statistics on part-time employment, i.e. those who work less than 40 hours during the past week), the growth in part-time employment has had reversed directions from those of growth in the GDP (except in 2008, the year when the slowdown in the global economy started to take effect). It appears that more jobs, but of less quality, were created during these periods of slowdown.

Figure 2. Annual Growth Rates in GDP, Full Time Employment and Part Time Employment, 2007-2013.

Source: PH Statistics Authority

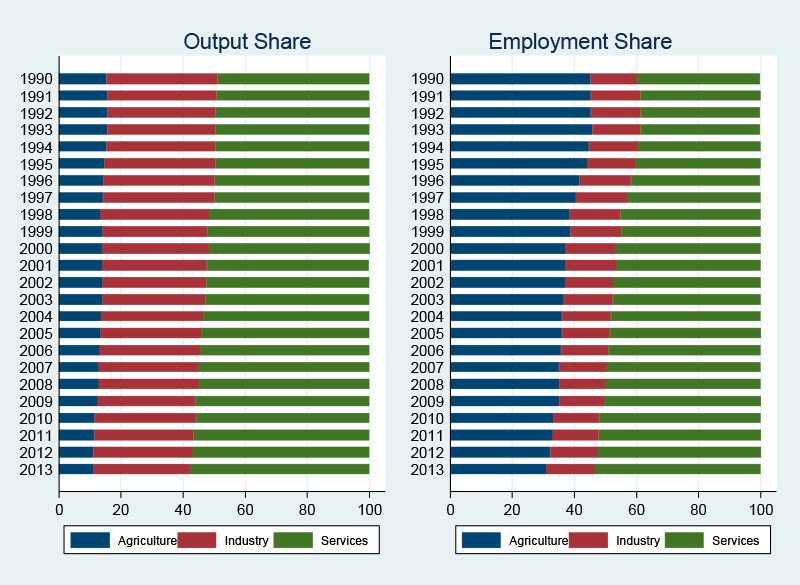

Another set of disaggregated employment statistics, i.e. employment by major sector, is also quite informative.

Dominated by services sector

When we juxtapose historical data on the shares of the agriculture, industry and services sectors on employment, with the corresponding shares in economic output, we find that the Philippine economy has always been dominated by the services sector, which currently has a share of more than half (57.7%) of total output.

The output share of agriculture to the economy has always been relatively minimal, less than a fifth of the country’s output for the past 25 years: 15.4% in 1990, and 11.2% in 2013. Even if we trace shares of major sectors all the way back to immediately after World War II, i.e., 1946, we would find that the shares of agriculture, industry and services sectors to the GDP then would be 29.7%, 22.6%, and 47.7%, respectively.

The economy has only become much less agricultural in recent times, and this has been the trend in many developing economies. The services and industry sectors are getting more of the share of the economy.

The decreasing trends in the share of agriculture are also seen in employment (see Figure 3), with agriculture’s share of employment decreasing from slightly less than half of total employment (45.2%) in 1990 to about a third (31.0%) in 2013.

In the same period, the service sector took increasing shares of total employment from two-fifth (39.7%) to more than half (53.4%). Industry, which had a share of about a 15.0% of aggregate employment in 1990, had its share go down slightly to 14.6% in 2009, and increase marginally to 15.6% by 2013.

In 2013, the largest growth in the country’s economic output of 9.5% came from the industry sector, which also had the highest growth in employment (3.4%) across the major sectors. Agriculture, which only had a mere 1.1% growth in output, even had a deceleration in employment figures.

All this may be suggesting that structural transformation in the economy is happening, even if overall employment rate has been relatively flat.

Shifting agriculture to industry

Thus, it’s not quite right to say that the Philippine economy has been having jobless growth.

The small net changes in the unemployment rates are the result of full-time jobs being created in the industry and services sectors, and part-time jobs lost in the agricultural sector. That’s good news folks! So, let’s not be quick in harshly criticizing government for every single thing.

Historically, the share of employment in industry has been lowest among the three major sectors. Even the current robust growth in output of the industry sector has not translated into more jobs (and lower unemployment) because of the low base figures of employment in the industry sector.

In the short term, for unemployment rates to drop considerably, employment growth must occur in agriculture (which has the highest share of employment). Volatility in employment (as well as in output) in agriculture, however, has been observed especially on account of extreme weather events.

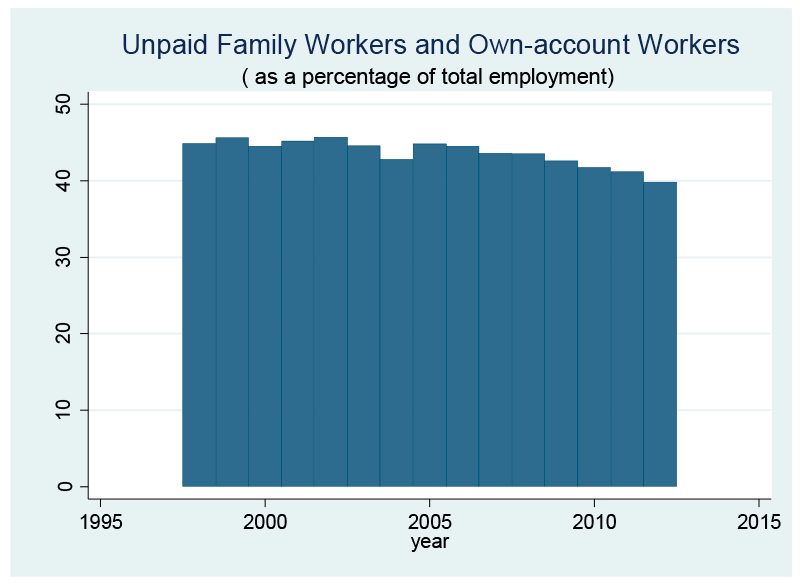

In the long run, employment should start shifting from agriculture to industry, the same path taken by many neighboring economies which are in better development conditions. There is also some evidence of a decreasing share of employment in vulnerable work (such as unpaid family workers and own-account workers).

While we need to expect highly of our leaders, let us also be realistic. While we have a Department of Labor and Employment that looks into employment issues, the government can hardly create more jobs.

Ultimately, the private sector, the main engine of the economy, is the source of more employment. Government can only provide the enabling environment, which it seems to have done with its focus on good governance and moral politics.

Let us just hope that our taipans, and even our entrepreneurs, continue to invest in the economy and create more jobs, particularly high-quality jobs. – Rappler.com

Dr. Jose Ramon “Toots” Albert is a professional statistician who has written on poverty measurement, education statistics, agricultural statistics, climate change, macro prudential monitoring, survey design, data mining, and statistical analysis of missing data. He is a Senior Research Fellow of the government’s think tank Philippine Institute for Development Studies, and the president of the country’s professional society of data producers, users and analysts, the Philippine Statistical Association, Inc. for 2014-2015.From 2012-2014, he served as Secretary General of the now defunct National Statistical Coordination Board.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.