SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

On Sunday, January 8, President Aquino was inside a police mobile bus command post when a bomb threat came in. That moment, according to those who saw him, seemed to have an impact on him. He asked for a briefing from the nation’s top security officials and announced a terror plot in an unprecedented Sunday press conference.

On Sunday, January 8, President Aquino was inside a police mobile bus command post when a bomb threat came in. That moment, according to those who saw him, seemed to have an impact on him. He asked for a briefing from the nation’s top security officials and announced a terror plot in an unprecedented Sunday press conference.

For the first time ever, the government asked all telecommunications companies to shut down their signals over a large chunk of Manila, ostensibly, to keep people safe.

Never mind that the alleged threat had been earlier dismissed by mid-level intelligence officials. After all, they’ve seen threats like this every year, and the source of information now was sketchy. One intelligence official quipped, “Bad assets must be in need of money.” That’s the danger when you pay cash for information and use double agents or informants.

There’s another danger for any novice evaluating threat information. So many pour in daily, and the source, intent, capability and networks must be assessed in order to determine whether it is “actionable intelligence.” This was not, according to a classified report which reached Malacanang and was obtained by Rappler.

All low-level and mid-level intelligence officials we spoke with Monday said the threat information wasn’t credible. One high-level official said the information was “fantastic,” but assured us that some of them had argued against the President’s plan to announce it publicly. I’m not sure that happened. Those close to him say Mr. Aquino can take it personally if you challenge him. The President was adamant. He believed it was “best to err on the side of caution” – a line echoed by all those around him, perhaps not understanding the impact of the decision they helped make.

This is what distresses me. According to multiple sources from the ground to the top of our security hierarchy, this was NOT a credible threat, but the attitude seemed to be to let the President have his way. After all, he’s the President. One source said, “Pabayaan mo na siya, Maria. Eh, siya naman ang Presidente.”

This is a problem. There are costs to decisions like this. It affects our image globally: the US and Australia immediately warned their citizens about the threat verified by Mr. Aquino. There were costs to businesses when the three telecommunications companies shut their services down. This is why decisions like this must be carefully calibrated and balanced.

I have no doubt Mr. Aquino had good intentions, but that isn’t enough. And what about the intelligence professionals who knew better? I struggled to find an answer, and I remembered a fascinating study about the Philippines’ power distance index.

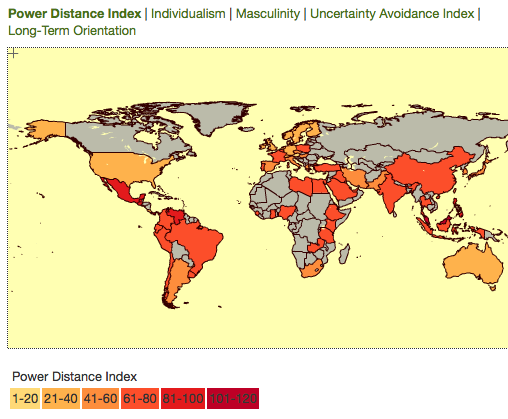

This is a bottom-up approach to measure how we feel and react to authority. A high power distance culture has people who accept the inequality of the power structure: a subordinate rarely challenges his boss and is often expected to take responsibility for any of his superior’s failures. A low power distance culture looks at people as equals, and work is a collaborative process.

The Philippines has the 4th highest power distance index in the world at 94 compared to the US at 40. This helps explain why Filipinos have such respect for authority; why people “know their place;” why true debate in an organization rarely happens if it includes the boss. It explains why we say “Sir” and “Ma’am” and why Filipinos can sometimes seem obsequious to Americans. The American janitor would think nothing of saying, “hey, Joe” to the CEO in the hallway – something a Filipino would rarely do.

What does this mean for those in authority? It means you’ll have to gather information and guard even more against your knee-jerk reactions and biases. Your subordinates will rarely contradict you – even if you’re wrong. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.