SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[ANALYSIS] Had Duterte acted earlier, PH economy would be safe to open by now](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2020/07/y4-economy-pandemic-July-17-2020.jpg)

In Duterte’s fourth year in office, it’s hard to think of anything else besides the pandemic and the twin crises – health and economic – it wrought.

Before the pandemic, economic growth – albeit decreasing – averaged at a decent 6.5% from the time President Rodrigo Duterte came into office until late last year. The unemployment rate continued its long-run decline. The poverty rate also remarkably went down from 2015 to 2018.

But things are way different now: the pandemic has upended everything.

In the first quarter of 2020 our economy shrank for the first time in two decades. Economists foresee worse figures for the second quarter, and reckon we’re already in the middle of a recession (or sustained economic downturn).

The unemployment rate also skyrocketed to a record high of 17.7%, with the economy shedding 8.9 million jobs in the short span between January and April. Self-rated poverty also spiked to its highest level since 2014.

Obviously, there’s a lot riding now on our economy’s full reopening.

In a forum ahead of Duterte’s State of the Nation Address (SONA), Finance Secretary Carlos Dominguez III – the head of the economic team – said that “increasing economic activity in a responsible manner is a matter of national survival and priority.” He added, “We need to strike a reasonable balance between safeguarding public health and restarting our economy.”

But with the new cases of COVID-19 skyrocketing in just the past days, we’re clearly far from striking any such balance.

The thing is, our economy would be safe to open by now if only the Duterte administration had responded to the pandemic much, much earlier.

Look at Vietnam

To see why, you need only look at Vietnam and its pandemic response.

By and large, life is back to normal there. Most businesses have resumed operations. People are flocking to malls and restaurants again. Students have gone back to school. Some tourist attractions and religious sites have been reopened.

If you think of it, the cards should be stacked against Vietnam. It shares a 1,300 km border with China. It’s a developing country like ours. It has a limited health infrastructure (having less than a thousand ICU beds) and not much resources for mass testing.

Despite all these, Vietnam managed to become one of the most inspiring success stories in the pandemic.

What saved the day was swift and transparent government action.

As early as January 15, a steering committee was convened to draw up measures against the possible rise of infections. Their Ministry of Health was ordered to issue guidelines on disease prevention and control, while their Ministry of Information and Communication was tasked to disseminate relevant information to the public.

On January 17, days before their very first case was confirmed, Vietnam implemented stronger quarantine measures at all airports, seaports, and border gates. The issuance of Chinese tourist visas was banned on January 30.

Luckily, owing to the Lunar New Year holiday, schools were closed as early as January 30, and the Vietnamese government kept it that way until the end of the spring semester.

On February 2, the Vietnamese prime minister had declared a public health emergency and banned all flights to and from China.

Targeted lockdowns were put in place as early as February 13, when they confirmed their 16th COVID-19 case. A nationwide lockdown was implemented on April 1, but they were able to lift it on April 22 – a mere 3 weeks later.

Most crucially, Vietnam didn’t think twice to implement widespread testing and contact tracing. They began developing locally-made tests as early as February. They came up with 4 types of test kits in total, the production of which they ramped up with the help of private companies.

Testing swelled rapidly: nearly a hundred days from the first confirmed case on January 23 until May 1, cumulative PCR tests conducted in Vietnam jumped from 10 to 266,122. But more impressively, Vietnam boasts the most number of tests per confirmed case – far exceeding other success stories such as New Zealand and Taiwan (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

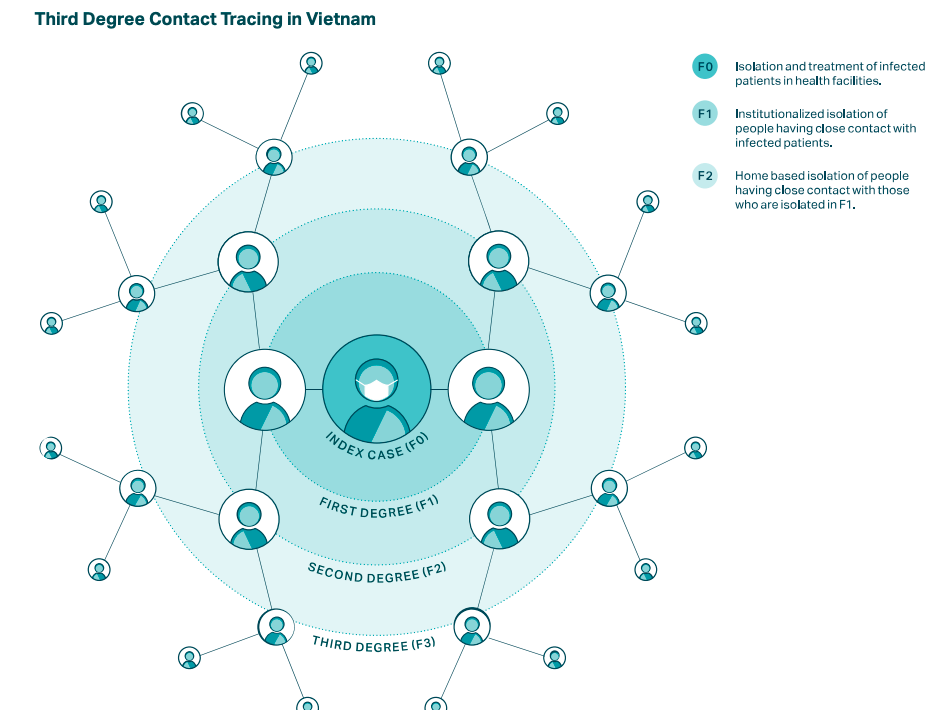

Vietnam also paired mass testing with strict quarantines and extensive contact tracing up to the 3rd degree from the infected person (Figure 2). By doing so, they were able to contain the virus before it was too late.

Figure 2. Source: Vietnam Ministry of Health.

Throughout, the Vietnamese government was in constant communication with its citizens about the pandemic and the government’s strategies. Heck, they even produced this uber-catchy PSA song:

![[ANALYSIS] Had Duterte acted earlier, PH economy would be safe to open by now](https://img.youtube.com/vi/BtulL3oArQw/sddefault.jpg)

We need to note that Vietnam’s pandemic response relied heavily on military resources, and according to some, were marred by human rights abuses. We have those in the Philippines, too. Yet the outcome could not be more different.

PH response: Inaction, complacency

In stark contrast to the prompt, decisive, and transparent actions of the Vietnamese government, the Philippine government’s pandemic response has been humiliatingly characterized by inaction and complacency.

On January 29, Health Secretary Francisco Duque III was still arguing in Congress that a ban on Chinese flights was not needed, saying “We have to be very careful also of possible repercussions of doing this, in light of the fact that confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus are not limited to China.”

Duterte did ban some Chinese flights on January 31, but it was limited to flights from Wuhan and Hubei and other areas where the virus had spread. By then, a woman from China (who later became the country’s first confirmed case) had already flown to Cebu and Dumaguete. A blanket ban on Chinese flights wasn’t put in place until February 2, and flights from other parts of the world weren’t blocked until March 12.

On Valentine’s Day, President Duterte was still inviting Filipinos then to “travel with him around the Philippines” in a bid to prop up the embattled tourism sector.

President Duterte did not order the suspension of classes until March 9, and even this was limited only to Metro Manila.

He later put Metro Manila under community quarantine on March 15, lasting about 2.5 months – among the world’s longest lockdowns.

Most alarmingly, the Duterte government repeatedly, unconscionably rebuffed strong public clamor for mass testing.

On March 20, when the country already had 230 confirmed cases, the Department of Health or DOH said they saw no need for mass testing, claiming we didn’t have enough resources anyway. Today testing remains grossly inadequate: on July 14 only 21,622 tests were conducted, far less than the 50,000 daily target they had set for June.

Contact tracing has also been feeble. Back in early February, Secretary Duque admitted in a Senate hearing they only traced 17% of passengers who may have come into contact with the two Chinese tourists who were the first confirmed cases. Fast forward to June 18, the country needed 135,000 contact tracers but fell short of 83,000.

Overall health spending has been wanting. The think-tank iLEAD showed that the DOH has spent just about half of its annual budget from January to May, with the additional P45 billion COVID-19 funds it got yet unaccounted for.

All in all, the Duterte government wasted a precious window of opportunity during which containment was at all possible. They acted too late, and now all Filipinos are paying the price.

The outcomes speak for themselves.

Figure 3 compares the epidemic curves of the Philippines and Vietnam. You almost can’t see the one for Vietnam: for many days now they’ve had zero new cases. By painful comparison, the epidemic curve for the Philippines continues to reach new heights. On July 16, new cases soared to nearly 2,500 – the second highest daily number on record.

Vietnam recorded a total of 381 cases as of July 17; the Philippines has 161 times that number.

In spite of the abysmal Philippine figures, on July 15 Health Secretary Duque had the gall to say that we’ve “successfully flattened the curve” – later amending that to “bent the curve” after he drew flak.

Figure 3.

Wobbly recovery

Because of the Duterte government’s delayed pandemic response, the Philippine economy will almost certainly take longer to recover.

Countries that acted promptly are now reaping the fruits of their early sacrifices. Their economies are mending, if not rebounding. Among the biggest ASEAN economies, only Vietnam is expected to grow this year, according to Bloomberg.

In the meantime, the Philippines is still busy playing around with its alphabet soup of quarantine acronyms, like ECQ, MECQ, GCQ, and MGCQ. Worse, previous lockdowns – especially ECQ in Metro Manila – seem to have been wasted given the unsettling rise of new cases.

Bafflingly, Secretary Dominguez and other economic managers are pushing for even looser quarantine restrictions in Metro Manila and other parts of the country, in a bid to revive the economy.

Reviving consumer spending is particularly crucial because it makes up about two-thirds of our economy. But until new cases approach zero, consumer spending can’t be expected to reach pre-pandemic levels. Huge swathes of the population will want to stay at home rather than go to the malls, eat out at restaurants, or travel.

Loosening restrictions prematurely might even lead to more cases and deaths. This is exactly what we’ve seen since Metro Manila was (partially) reopened and was downgraded to general community quarantine last June 1.

The new upsurge of infections is not only overwhelming hospitals – we’ve already reached the “danger zone” last July 14 – but might also necessitate future lockdowns, further damaging the economy.

To escape this vicious cycle, government must put the health crisis front and center.

Infrastructure fetish

Unfortunately, for some time now, the Duterte government has had its priorities wrong.

In particular, Duterte’s economic team is adamantly pushing for big-ticket infrastructure development as their preferred path toward recovery.

In the first pre-SONA forum, Secretary Dominguez said, “We are maintaining our Build, Build, Build program. Infrastructure projects will be the best way to revive the economy because of their high multiplier effects, stimulating demand and generating new jobs and businesses.”

At the same time, the House of Representatives already passed on third reading a P1.5 trillion CURES bill (COVID-19 Unemployment Reduction Economic Stimulus) that aims to jumpstart the economy through local infrastructure projects over the next 3 years.

In China, there’s some evidence to suggest that infrastructure spending did lead to the surprising 3.2% growth of the economy in the 2nd quarter (in contrast to the dismal 6.8% contraction in the previous quarter). But since consumption spending remained muted, analysts deem this growth – heavily reliant on government stimulus – unsustainable.

Likewise, in the Philippines, infrastructure projects will only go so far. Until consumer confidence bounces back, hopes for a full economic recovery are nil.

Note that Duterte’s Build, Build, Build projects have previously been stymied by myriad bottlenecks. In fact, last year the economic team had to adjust their targets after realizing that some of their original proposals were wholly unfeasible.

Relying too heavily on local infrastructure projects might also pave the way for more pork allocations for lawmakers, feeding graft and corruption in the last two years of the Duterte administration. (READ: Why we can’t Build, Build, Build our way out of this pandemic)

Infrastructure funds will be much better poured into the current pandemic response, namely testing, contract tracing, and treatment. (READ: Test, Trace, Treat (not Build, Build, Build))

Needless scrimping

The recession might also be somewhat more bearable if only government pulls out all the stops and spends aggressively on economic aid.

But Duterte’s economic managers are needlessly scrimping. This, despite the hundreds of billions worth of new loans and grants raised by government in the past few months. (READ: Duterte’s new COVID-19 loans: Need we worry?)

Evidently, the economic team will do anything to keep the government’s budget deficit (or revenue shortfall) on or below a ceiling of about 9% of the nation’s income – even if that means playing a scrooge and withholding much-needed economic aid for the poor, the middle class, and business owners.

The now expired Bayanihan to Heal as One Act provided for two months’ worth of emergency subsidies for 18 million households nationwide. But that was good only for April and May, and government has yet to complete all cash transfers for May. Further aid is not yet forthcoming for millions of households continuing to suffer nationwide.

Workers, too, need a lot of help, like wage subsidies for those who still can’t go to work, or adequate health protection and transportation for those who can.

But government can’t even acknowledge the extent of the labor crisis. Labor Secretary Silvestre Bello III said that only 69,000 people were jobless, even if the official figure said 7.3 million.

In the middle of a pandemic, Duterte chose to compound workers’ woes by denying the franchise renewal of ABS-CBN – a move that puts at risk tens of thousands of jobs, among other dire economic effects.

Several businesses are already closing down. One undersecretary of the Department of Trade and Industry was recently close to tears in one webinar because her agency simply could not provide aid for thousands of businesses approaching their office and pleading for any form of relief.

Government should act quickly to aid businesses, especially small ones which make up the vast majority of firms nationwide. If thousands of them are allowed to die, what recovery is there to speak of later?

Secretary Dominguez earlier said that aid for firms will “take a back seat.” Inscrutably, their team would rather keep the deficit low than keep firms afloat.

Some lawmakers are pushing for well-crafted economic rescue packages, like the P1.3 trillion ARISE Philippines bill. But Duterte’s economic managers are lobbying for their own stimulus package called Bayanihan to Recover as One – a bill that disturbingly allocates a lot less money for aid. The economic team also dismissed proposals for a supplemental budget, saying (misleadingly) that we can’t afford it.

On top of all this, some “stimulus” bills are replete with red flags. For instance, the ARISE bill has been inserted with a number of questionable provisions that could dangerously erode business competition in the country (weak as it is) and curtail the powers of the Philippine Competition Commission.

Some also worry these provisions might open the floodgates for cronyism – nay, a new oligarchy? – during the pandemic.

The real Duterte legacy

On some level, you might argue it’s useless to rant about the government’s complacent pandemic response. Nobody can turn back time to right the many wrongs and exploit the opportunities we missed back in January and February. We just need to battle on.

But when you think of the 1,643 people who died so far and the families they left behind; the 61,266 people who caught the virus one way or another; and the 110 million Filipinos who have largely been left by their government to their own devices – it becomes clear as day that we have to document in excruciating detail exactly what went wrong and how we got here.

In January, when the pandemic was still incipient, the Duterte government launched an information campaign called the “Duterte Legacy,” which lists the administration’s achievements so far. As you might expect, it’s full of spin.

Here are 3 things the true list should include: the bloody war on drugs, the wholesale erosion of our democratic norms and institutions, and the continuing catastrophe that is Duterte’s pandemic response. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler’s Best] US does propaganda? Of course.](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/06/US-does-propaganda-Of-course-june-17-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=236px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

![[OPINION] Rodrigo Duterte and his ‘unconditional love’ for China](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/04/rodrigo-duterte-xi-jinping-august-2019.jpeg?resize=257%2C257&crop=91px%2C0px%2C900px%2C900px)

![[The Slingshot] Lito Patay’s 4 hours and 38 minutes of infamy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/07/Lito-Patay-4-hours-infamy-July-19-2024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=233px%2C0px%2C720px%2C720px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.