SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

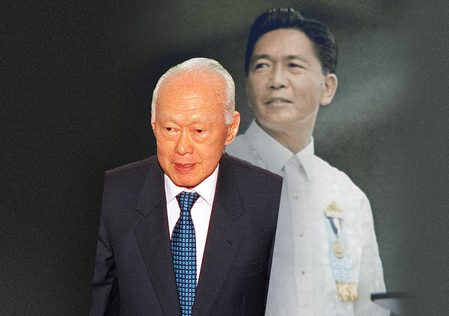

![[OPINION] It’s final: Duterte is no Lee Kuan Yew](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/03/20230315-duterte-no-lee-kuan-yew.jpg)

Transparency International has recently released its 2022 Corruption Perception Index (CPI), which ranked the Philippines 116th out of 180 countries, with a 33/100 CPI score — our lowest since 2012. Additionally, the Philippines was identified as one of the “significant decliners,” having sharply dropped from 38 to 33 in eight years. Finally, it can be said the Philippines has only gotten more corrupt during the Duterte administration.

Ironically, former President Duterte was touted as the “Lee Kuan Yew of the Philippines” during the campaign period and in the first years of his presidency. Duterte promised the eradication of corruption, saying: “I can’t promise heaven, but I will stop corruption. In three to six months, I will stop corruption.” Because of his strongman style of leadership and anti-corruption stance, several analysts (including UST’s economics department chair) proclaimed Duterte as the solution to the long-standing economic problems of the country.

What these analysts failed to realize was that the campaign of Lee Kuan Yew started with establishing a solid foundation for the rule of law. Lee believed that Singapore had to create the societal conditions in which the rule of law would prevail for there to be economic prosperity. In other words, the citizens needed to live in a society free from its leaders’ unjust and arbitrary decisions and where the authority of the law is observed and respected.

Anti-corruption as a core in establishing the rule of law

When Lee Kuan Yew assumed office as the prime minister of Singapore, then a self-governed British state, he inherited a legacy of corruption left by the Japanese Occupation and the British Military Administration. Notably, from the 1950s and 1960s, Singapore was plagued by crime, disorder, and subversion.

One of the essential steps the former Prime Minister undertook in creating an environment where there is a rule of law was implementing a comprehensive anti-corruption strategy characterized as “credible, effective, relentless, [and] pursued without fear or favor.” This includes the legislation of the Prevention of Corruption Act, the provision of adequate personnel and funding to the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau, the payment of competitive salaries to senior government officials, the prohibition of gift-giving to civil service personnel, and the punishment of all corrupt acts, without regard to the offender’s political affiliation or social standing.

Duterte’s actions towards corruption during his term can be described as the opposite of Lee’s. Let me give some examples.

For one, Duterte appointed his social media strategist Pompee La Viña as commissioner of the Social Security System who will later be subjected to several allegations of corruption. The Duterte administration, through Harry Roque, initially used La Viña’s non-extension as commissioner as evidence of Duterte’s non-tolerance of corruption. Duterte, however, would later reappoint La Viña, first as undersecretary, then later as a GOCC administrator. Another Duterte-appointee, Isidro Lapeña, was involved in one of the biggest shabu scandals with the Bureau of Customs, amounting to P11 billion. Lapeña was removed following the incident but was later “promoted” to a higher position in another agency. Duterte rationalized this by saying that Lapeña still had his trust and confidence despite the number of corruption cases filed against the latter by the government itself. Duterte also appointed former Supreme Court Associate Justice Martires as Ombudsman, whose first acts included stopping the practice of lifestyle checks and the release of the SALNs of government officials to the public. Finally, Duterte also contradicted his own anti-corruption stance when he refused to reveal his SALN despite allegations of hidden wealth.

Just like Duterte’s promise of eliminating drugs in six months, his promise of ending corruption ended up becoming mere lip service. The corruption scandals that took place during his administration such as the PhilHealth plunder, the “pastillas” human trafficking scheme, and the two instances of shabu smuggling — all involving billions of pesos — were never resolved. By 2021, Duterte conceded that eliminating corruption was “impossible and cannot be achieve[ed].” Whether or not he actually tried to eliminate corruption — in hindsight — remains disputable, considering how he, directly and indirectly, contributed to furthering corruption.

The rule of law and economic development

While there may not be conclusive empirical studies linking the decrease in corruption with economic prosperity, there seems to be a consensus among most states regarding the benefit of a strong rule of law to a country’s development. In the Declaration of the High-level Meeting on the Rule of Law, Member States noted that “the rule of law and development are strongly interrelated and mutually reinforcing” and that “the advancement of the rule of law at the national and international levels is essential for sustained and inclusive economic growth, sustainable development, the eradication of poverty…which in turn reinforce the rule of law”.

For Singapore, the role of the “rule of law” has always been clear. In his article published in the Singapore Journal of Legal Studies, former Minister of Affairs and Minister of Law K. Shanmugam said that what defined Singapore, among other things, was equality before the law and intolerance of corruption. He was further quoted saying, “we reali[z]ed that our ideals and aspirations could only be reali[z]ed through the law and the legal framework. Foreign investment would only come if we could provide the necessary legal certainty. In that sense, the Rule of Law was for us not only an aspiration and an ideal…but also a necessity borne out of exigency.”

In fact, from 1965 to 2011, the GDP per capita of Singapore rose from $500 to $72,000. Notably, Singapore is currently ranked 4th in CPI, while the Philippines is ranked 116th. In terms of GDP per capita, on the other hand, Singapore has a GDP per capita of $98,526, while the Philippines only has a dismal $8,390.

The Marcos legacy

Unlike former president Duterte, President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. never included anti-corruption in his campaign. In fact, in his first State of the Nation Address, Marcos, did not mention the word “corruption.”

The idea of corruption will forever be linked with the Marcoses due to the rampant corruption committed by the president’s father and namesake, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr., who plundered an estimated amount of $5-10 billion. Despite this, President Marcos, Jr.’s first Executive Order was to abolish the Presidential Anti-Corruption Commission. While the purpose was allegedly to “streamline” government functions, this made it more difficult for the public to monitor anti-corruption efforts. Additionally, allegations that the Maharlika fund will be used for corruption have also been gaining steam after it was railroaded in the House of Representatives, spearheaded by key legislators who belong to President Marcos’ family.

With this lack of anti-corruption initiatives, it is unlikely that the Philippines will become like Singapore soon — no matter how many merlions we install in our parks. Perhaps being compared to Singapore’s greatest leader is not in President Marcos Jr.’s priorities. After all, it was Lee Kuan Yew who said, “only in the Philippines could a leader like Ferdinand Marcos, who pillaged his country for over 20 years, still be considered for a national burial. Insignificant amounts of the loot have been recovered, yet his wife and children were allowed to return and engage in politics.” – Rappler.com

Juan Paolo Artiaga is a lawyer by profession, and currently a Master in Public Policy student at the National University of Singapore.

1 comment

How does this make you feel?

Wow! So the problem isn’t that Duterte was autocrat, it’s that he didn’t use his autocratic tendencies to get rid of corruption? The tendency to see Singapore as a model is a little disturbing.