SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – Correct information is vital to decision-making, and calling out false information as you see it online is now indispensable more than ever.

Because of this, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) recently published a handbook for journalism anchored on combating “fake news” and disinformation.

Emphasizing that calling out disinformation is “mission critical,” the handbook is both a guide and a “call to action.”

Unesco describes Journalism, ‘Fake News’ & Disinformation as a “model curriculum…designed to give journalism educators and trainers, along with students of journalism, a framework and lessons to help navigate the issues associated with ‘fake news.’”

Kinds of untruths

In the handbook’s overview, Unesco says it “avoids assuming ‘fake news’ has a straightforward or commonly-understood meaning.” According to the handbook, the term is an oxymoron which undermines credible information of public interest. This is shown in the strikethrough line on the term in the title.

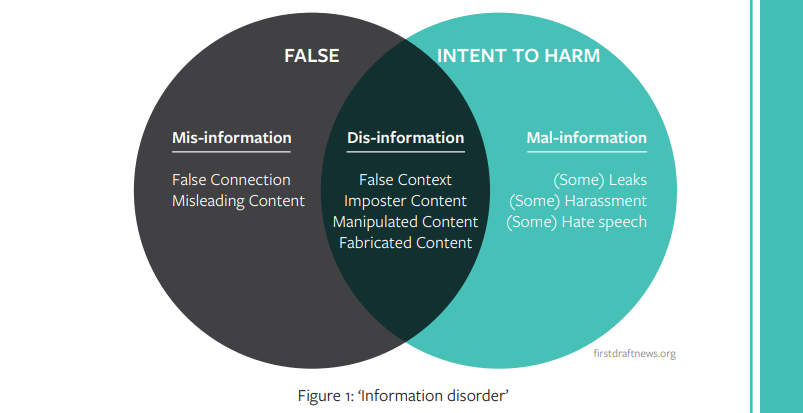

Three types of untruths are listed in the handbook’s landing page:

- Disinformation, which is blatantly false and created to harm an individual or group

- Misinformation, which is also false but not intended to harm others

- Mal-information, which is based on reality and used to harm others

To confront these untruths, the handbook has two parts: the first 3 modules explain and contextualize the “disinformation crisis,” and the last 4 are a manual on how to respond.

The 7 modules are:

-

“Truth, Trust and Journalism: Why it Matters” by Cherilyn Ireton, a South African journalist who directs the World Editors Forum, within the World Association of Newspapers and News Publishers (WAN-IFRA).

-

“Thinking about ‘Information Disorder’: Formats of Misinformation, Disinformation and Mal-Information” by Claire Wardle and Hossein Derakhshan. The former is the executive director of First Draft News, and a research fellow at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at the Harvard Kennedy School. The latter is an Iranian-Canadian writer, researcher, and fellow at Shorenstein Center at Harvard’s Kennedy School.

-

“News Industry Transformation: Digital Technology, Social Platforms and the Spread of Misinformation and Disinformation” by Julie Posetti, a senior research fellow at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism at the University of Oxford, where she leads the Journalism Innovation Project.

-

“Combatting Disinformation and Misinformation Through Media and Information Literacy” by Magda Abu-Fadil, the Lebanon-based director of Media Unlimited.

-

“Fact-Checking 101” by Alexios Mantzarlis, who leads the International Fact-Checking Network at the Poynter Institute.

-

“Social Media Verification: Assessing Sources and Visual Content” by Tom Trewinnard and Fergus Bell. The former is the program lead of Check, Meedan’s open source verification tool. The latter is the founder of Dig Deeper Media.

-

“Combatting Online Abuse: When Journalists and Their Sources are Targeted” by Julie Posetti

” data-auto-height=”false” data-aspect-ratio=”0.75″ scrolling=”no” id=”doc_11966″ width=”100%” height=”600″ frameborder=”0″>

Why is there a ‘disinformation crisis’?

The internet, as an open space where everyone can be a publisher, has a downside. Readers are exposed to information that may be unverified or entirely false. It allowed free participation but ended up undermining democracy itself, the handbook explains.

In recent years, the world, especially the Philippines, has been the target and source of disinformation. Rappler CEO Maria Ressa explained in 2016 how internet trolls work in her three-part series starting with “Propaganda War: Weaponizing the Internet” which the handbook cited as an effort to counter disinformation.

In the second module, which teaches readers how to consume information better, the process and format of false information is discussed. For example, a false claim coming from a mastermind of a “disinformation campaign” is different from trolls that mobilize actions based on the campaign’s agenda.

And where these activities are happening is also important. A false claim online can reach more people than a claim on print, as explained by the third module. Journalists need to catch up with this by modifying methods on content production: focusing on digital and engaging in other platforms.

The module aims to help people understand how the rise of disinformation and misinformation affected the news industry.

From a teacher-student perspective, the 4th module aims to promote Media and Information Literacy (MIL). It emphasizes what false claims look and sound like. It explains that young readers engaged in mobile devices should develop a “healthy skepticism” in relation to all information they encounter, offline or online.

The basics of fact-checking

The handbook cites the 2009 Pulitzer award given to Politifact as “significant to the growth of this journalistic practice (fact-checking).”

PolitiFact started in 2007 as an election-year project of the Tampa Bay Times (then named the St Petersburg Times), Florida’s largest daily newspaper. The award was for their coverage of the 2008 United States national elections which focused on fact-checking campaign claims and promises.

The format is explanatory, emphasizing what the claim or promise is, and rating it from False to True, provided with explanation. The 5th module teaches this and teaches the difference between fact-checking and verifying:

- Fact-checking “results in a conclusion on a claim’s veracity.”

- Verifying “results in a story being published – or stopped.”

To provide examples, statements of political leaders and known figures are laid out in the handbook and each claim in it is either highlighted red for statements that cannot be fact-checked, green for statements that can be fact-checked, and orange for anything in between.

The 6th module teaches how to find sources and references that can be used to debunk or verify these claims, visual and textual. The handbook lays out different methods: interviewing eyewitnesses, comparing personal accounts, Facebook account analysis, and Google reverse image search.

But fact-checking can be risky. In a number of countries, fact-checkers have been targetted by trolls.

Thus, the last and 7th module’s concern is the welfare of the journalist. What can one do when harrased? Accounts from journalists who had the unfortunate experience of being attacked by trolls are explained. One journalist said the first thing to do is to recognize threats, while another journalist suggested using investigative stories to “fight back.”

Overall, the handbook should be helpful for anyone: students, teachers, journalists, the academe, and the general public. It has a structured format consisting of a synopsis, outline, aims, learning outcomes, module format, suggested assignment, and readings.

A subtle reminder for the journalist is found in the handbook: transparency is the new objectivity. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.