SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

With the US election just a few days away, the fate of Filipino “dreamers,” undocumented immigrants brought to the US as minors, hangs in the balance.

If President Donald Trump gets reelected, he would again push for the end of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which protects around 700,000 “dreamers” or DACA recipients from deportation. The Supreme Court earlier blocked Trump’s move but the President has not yet given up on terminating the program.

Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden, meanwhile, vowed to reinstate the DACA program, which the Obama-Biden administration created in 2012.

DACA grants dreamers the temporary right to live, study, and work legally in America. If approved in this program, children are safe from deportation for two years, subject to renewal.

According to the US Citizenship and Immigration Services, there are around 3,270 active Filipino DACA recipients as of March 31, 2020. The Philippines has the second highest DACA recipients among Asian countries, trailing South Korea (6,210 recipients) and followed by India (2,290 recipients).

With no right to vote, two DACA recipients Rappler spoke with have spent their time educating people on immigrants’ rights, as well as the need to vote.

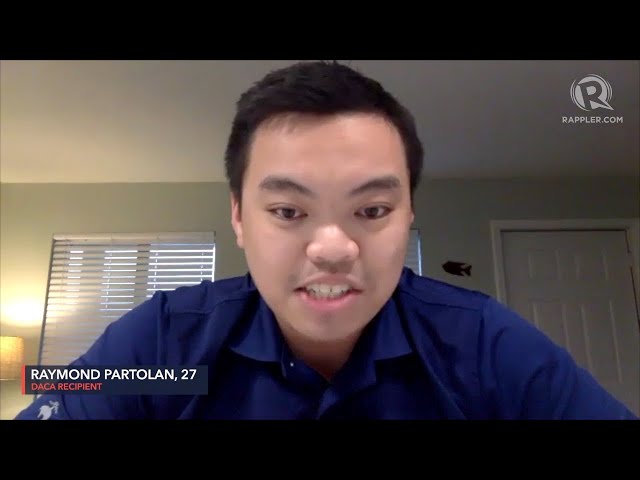

“As undocumented, the only way I truly feel I can influence public policy and the decision-making process that affects my life, is to encourage people around me who have the right to vote to exercise that vote,” Raymond Partolan, 27, told Rappler in an interview.

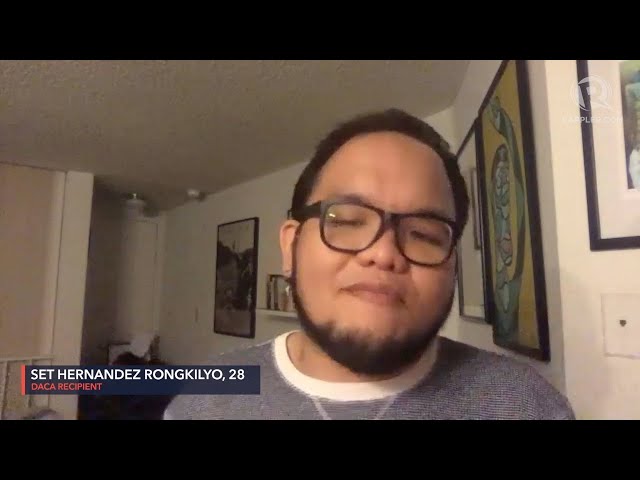

“I’m politically engaged beyond just voting…. I may not be able to vote but I share my political power in different ways. My organizing is on migrant justice and also media justice, making sure that those whose stories are being told also have the power to tell their stories for themselves,” 28-year-old Set Hernandez-Rongkilyo said in an interview with Rappler.

The story of Raymond

Partolan and his family moved to Macon, Georgia, when he was just a year old. They immigrated using his father’s skilled worker (H1B) visa as a physical therapist.

He became undocumented when he was 10 years old. His father applied for a permanent residency visa but failed to get one after repeatedly failing the speaking section of the TOEFL. Because he did not get the visa, he also lost his job, leaving Partolan’s mother working 4 jobs to sustain their family of 5.

Growing up as an undocumented immigrant had an “enormous impact” on his life. Hiding in the shadows, he could not do what the average American kids could do. Even when he was a straight-A student, he knew that attending college would be an uphill battle. Public universities would not accept him, while private universities would charge him more.

“I was devastated. It was difficult to have the will to continue to live. I tried to commit suicide because I felt that was the only way to escape the pain and suffering that I felt as an undocumented…. I’m very thankful my suicide attempt was unsuccessful but that’s the turning point for me to do everything in my power to help advocate for the Filipino undocumented community,” Partolan said.

DACA, he said, greatly changed his life.

“Before it was announced in 2012, I wasn’t able to drive, I couldn’t work without an employer questioning me about my immigration status or whether or not I was authorized to work in the US. I think most importantly, what DACA did for me was it pulled me out of the shadows I was living in and it allowed me to come out and more boldly advocate for myself and for people around me who are also undocumented,” Partolan said.

“DACA finally lifted from my shoulders the fear and anxiety that I was feeling as an undocumented person. That would be the case for so many thousands of DACA recipients,” he said.

Partolan eventually got a full scholarship at Mercer University and graduated with the highest honors. After college, he went on to work at a firm supporting immigrants’ rights.

But things got difficult for the family ahead of the 2016 presidential election, which saw Trump as the winner. Partolan’s parents are also undocumented immigrants, while his two brothers are US citizens, having been born there.

“We were worried he was gonna fulfill his promises and round up undocumented people. It was a difficult time for our family. We began to talk about potential family separation. My parents and I would have to live with the possibility that we will be separated from my two brothers,” Partolan said.

He added: “We started to develop a family response plan…. You actually come together and you talk about things like when your parents get picked up by authorities, where are your younger US citizen children gonna go? At that time, my 10-year-old brother was crying because he could not live away from us.”

Fortunately, one brother was able to petition their parents when he turned 21 years old. Now, theirs is what Partolan calls a “quintessential mixed status family,” with two US citizens, two permanent residents, and one undocumented.

The story of Set: Seeking identity

Filmmaker Hernandez-Rongkilyo was 12 years old when his family moved from Caloocan to the United States for a chance at a better life. They initially wanted to move to Japan, where his parents first worked but decided otherwise due to the language barrier.

Everything was doing well until his mother lost her job, and with it her status, during the recession. The family then became undocumented.

On top of this double loss, they were among the victims of immigration lawyer Philip Abramowitz, who was later on charged with fraud.

Hernandez-Rongkilyo said he does not necessarily fear being deported. After all, he said, there are many undocumented people who are far more productive and valued when they transferred to other countries. But what saddens him is the prospect of moving to another country – again.

Children of immigrants have already struggled finding their identity, something even more difficult for undocumented people.

“I think being plucked out of the place you call home, that’s something that is more difficult to think about…. This place is where I grew up in. This is as close as home gets. I moved so many times, am tired of moving. I just wanna bloom where I’ve been planted,” he said.

While he has received opportunities through DACA, it still was not enough for him, as he sees the challenges for his undocumented mother, who is now in her 60s and who continues to work as a bookkeeper and pays taxes.

“I remember when Trump became president. A mentor of mine had mentioned a dream my mom had shared. In her dream, she was on the bus, when ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] agents entered to remove her. I never heard this story directly from my mom – maybe because she didn’t want me to worry. But I often ask myself: Is DACA really as good as they claim it is, when my dad can’t even return to his family and my mom has nightmares of ICE taking her?”

“It’s not just about me. I am part of a family. I am part of a community. My wellness depends on their wellness too.

“The unjust irony is that because of her immigration status, my mom can’t access the very public services that she helps her clients contribute to and that she herself contributes to through her own tax dollars.”

Changing the narrative

Hernandez-Rongkilyo, a student at the University of California, Los Angeles, also wanted to redefine the persisting narrative about undocumented individuals, especially DACA recipients.

Passing the blame on to the dreamers’ parents, he said, is premised on the wrong assumption that their immigration status is entirely their parents’ fault.

“What we also need to look at is the circumstances, via the lens of politics,” he said, citing his family’s own experience.

“Some would argue, ‘Bakit ‘di na lang kayo umuwi (Why don’t you just go home)?’ It’s more complicated than that. She could leave anytime, but I think the sacrifices as a mother, because she recognized that for her kids, our lives were already molded here, this is now our home. My mom, even though she feels conflicted where she really belongs, is staying here for us,” he said.

He also pushed back against media portrayal of DACA recipients, as he co-founded Undocumented Filmmakers Collective, which seeks to focus on undocumented people as creators and artists, not just sources of stories.

Trump vs Biden

While the Supreme Court rejected Trump’s move to cancel DACA, the fight is far from over.

“The decision does not contemplate the legality of the DACA, only the manner by which Trump ended the program. Theoretically, the Trump administration could move to end it again to follow admin procedures,” Partolan said.

“This is only the beginning. This is a big win but the fight must continue. We will not stop fighting,” he added.

Of the two candidates, Hernandez-Rongkilyo said Biden is more likely to listen and act on their advocacies.

“We’re not choosing who’s gonna save us, we’re choosing who’s gonna be a target for our organizing. Trump is not gonna be moved. Biden at least, I feel, has a sense of shame. You can’t shame Trump, he is shameless. Biden at least, we hope, and Harris have more ways to push them,” he said.

As the world waits for the new leader of the free world, these dreamers have no choice but to wait and see if they will finally belong to the place they have called home. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.