SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

When their intimate materials spread online, victims of online sexual abuse are faced with a tough choice: Report for the immediate takedown of the materials for their peace of mind, or allow them to stay up on the sites for evidence purposes.

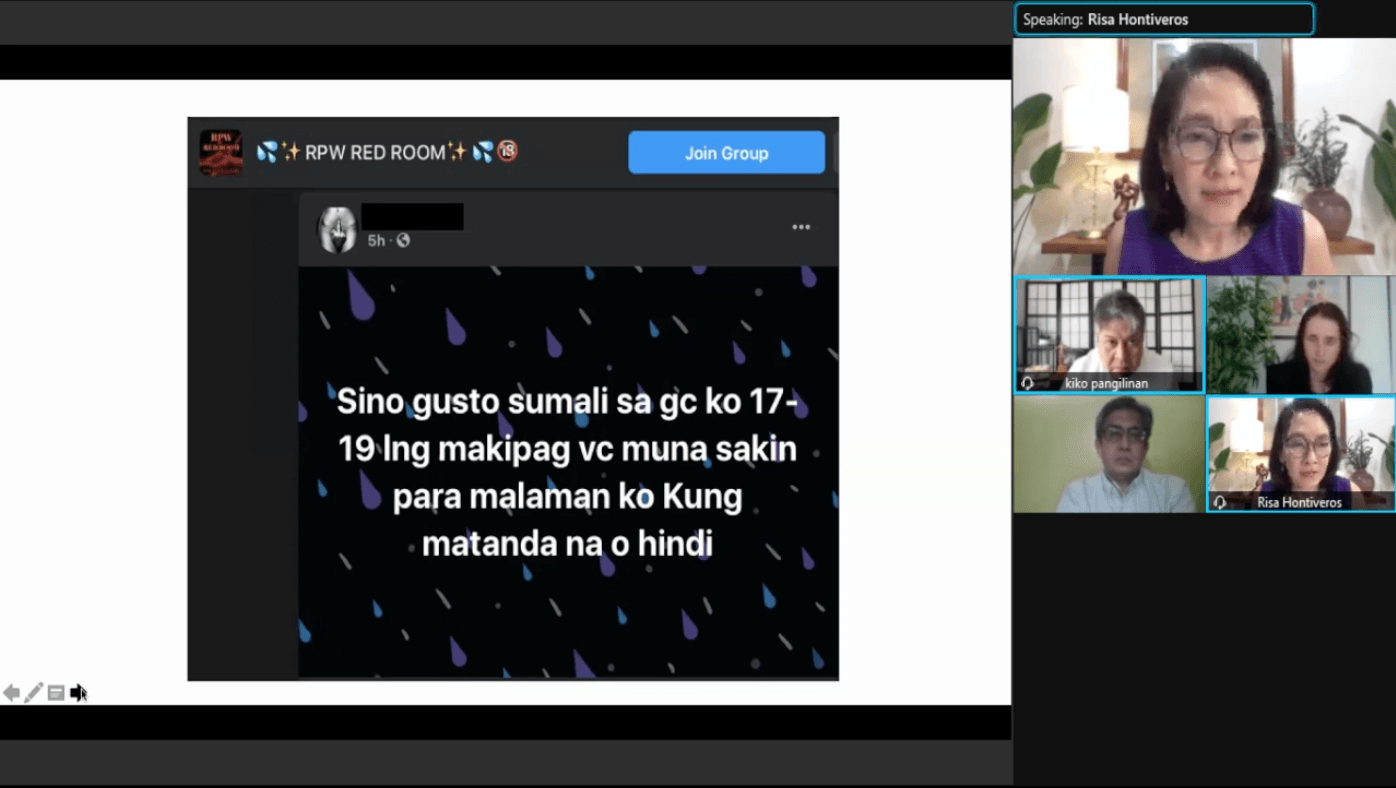

Realizing that their materials spread, victims tend to immediately want the platforms to take them down, Jelen Paclarin of the Women’s Legal and Human Rights Bureau said during a Senate hearing on Tuesday, March 9.

Ria, a survivor of revenge porn who spoke at the hearing, said she felt like her online harassment would never end. “I was feeling helpless, since I was unable to stop the spread of the photos,” she said as she recalled the abuse. Her surname was withheld during the hearing.

However, in cases where materials are taken down, the evidence is unlikely to be preserved. Paclarin said that the challenges in filing a case include how the victim’s testimony is not enough.

Besides, not many young people know how to properly preserve digital evidence.

Representatives of Facebook and Google said in the hearing that they were implementing technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning tools that can proactively detect abusive material, even before these are reported.

Senator Risa Hontiveros, who led Tuesday’s hearing on bills related to abuses against women and children, said the law needed to “bring together the tech and the law enforcement sides closer together.”

The problem with reporting

According to Kev, who also spoke in the hearing as someone who experienced having his intimate materials spread online without his consent, reporting doesn’t really solve the problem, either. Kev’s surname was also withheld.

Kev and Ria are part of a support group that uncovered an “elaborate network of revenge porn.” They turned to reporting on the platforms where they were found – one of which was Google Drive.

“In some platforms, just reporting it will take it down, but that doesn’t mean it’s gone, it just means that it’s going to happen elsewhere,” said Kev.

Kev and Ria said materials monitored by their group have spread on mainstream platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Hoop.

‘Bad experience’ with enforcers

Paclarin said that many of the survivors who come to their group for help say that they had “bad experiences” when seeking help from the police. She said the police would sometimes resort to victim-blaming – asking them why they chose to send nude photos in the first place.

Ria, who was 16 when her abuse started in 2011, tried to pursue legal action in 2013 for sextortion on Facebook. This happens when an abuser messages a victim saying he or she is in possession of the victim’s nude photos, and threatens to spread them if the victim does not send more.

“I went to the [National Bureau of Investigation] first, but they told me that to get a legal verification request to Facebook through the [Department of Justice or DOJ], it would have taken 6 months,” said Ria.

Anonymity of perpetrators

According to Angiereen Medina from the DOJ’s cybercrime office, one of the biggest challenges in going after perpetrators is that they do not use their real names when engaging in abuse on social media. Ria said she experienced this.

“The anonymity of these perpetrators allows them to commodify my body forever, granting access to virtually everyone,” said Ria.

Medina said the only lead would be an Internet Protocol (IP) address, but an IP address can’t always immediately trace the abuser, especially if it’s IP version 4 (IPv4).

“[Internet providers] explained that given the exhaustion of IP addresses under IPv4, they are constrained to use a technology that bundles users, so that a lot of users are sharing one single public IPv4 address,” said Medina.

Concerned agencies like the DOJ are advocating for IPv6 implementation in the country, which would narrow down users associated with certain IP addresses.

The National Telecommunications Commission earlier issued show cause orders for internet providers for their failure to block child sexual exploitation materials. The technology department later explained that internet providers cannot detect abusive material real-time, especially since they do not host content.

“If the people tasked [to protect] us don’t understand the urgency and situation, if their first instinct is to conceal the fact that we are reporting or [if they] punish us for reporting in the first place, impunity will only grow,” said Ria.

“While the internet may seem like just the medium for committing these crimes, these crimes exist on a global scale because of the internet,” she added. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[Rappler Investigates] Sexual harassment by the boss](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2024/02/sexual-harassment-by-the-boss-02292024.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop=414px%2C0px%2C1080px%2C1080px)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.