SUMMARY

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![[OPINION]: The good with the bad: Reappraising the Aquino legacy](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/06/IMHO-PNoy-June-25-2021.jpg)

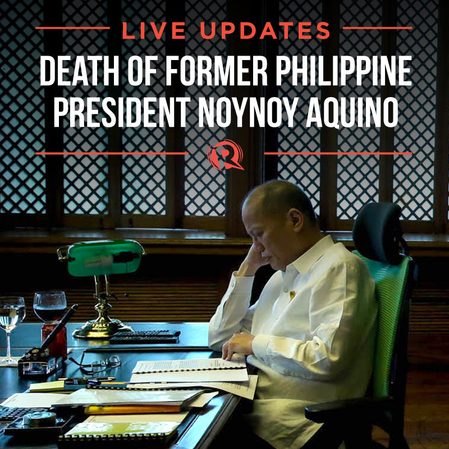

On the morning of June 24, 2021, the nation was caught unawares by the news that former President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III, 61, had passed away after being rushed to the Capitol Medical Center in Quezon City. His death comes only five years after stepping down from the presidency, when he was succeeded by Rodrigo Roa Duterte.

Aquino, who had been absent from public life ever since, had lived on to be a polarizing figure in the country’s politics. Yellow (dilaw) – that iconic color of both the Aquinos and the Liberal Party – has become a byword (dilawan) for critics of the current Duterte regime, and of the Marcos regime decades before it – toppled as it was by the EDSA Revolution and the Aquino tandem that served as its figureheads.

“PNoy,” as he was popularly known, won a landslide victory during the 2010 Philippine presidential election, carried by a whirlwind of emotions following the death of former President Cory Aquino and the promise of a “Daang Matuwid” – an anti-corruption platform in stark contrast to the scandal-ridden tenure of his predecessor, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo. Whereas Arroyo’s brand of leadership bore witness to an unprecedented level of self-aggrandizement and abuse of executive power, Aquino had styled himself the nation’s servant. To the Filipino people, he had always boasted: “Kayo ang boss ko.”

The extent to which this was true was and continues to be a point of contention. On one hand, his administration effectively set the stage for the Philippines to become one of the fastest growing economies, not only in the East Asia region but in the world, peaking in 2010 (7.3% annual GDP growth) and again in 2013 (7.2% annual GDP growth) – a trend which has undeniably carried over to the present Duterte administration. At the same time, however, this economic boom had disproportionately benefited the country’s elite, failing to trickle down to the general public, where continued social, political, and economic inequality stand contrary to true inclusive development. We remember, for example, the calls of farmers, fisherfolk, and indigenous communities alike against the incursion of the Aurora Pacific Economic Zone and Freeport (APECO) on their livelihoods and ancestral domains – a project Aquino had vigorously backed and defended during his administration.

His tenure was no stranger to controversy. Aquino inherited a failed and bloody history of agrarian reform, a fact which continues to haunt the democratic legacy of the dynasty to this very day. Only two months into his presidency, he blundered his way through the Manila Hostage Crisis. Aquino’s campaign slogan, “Kung walang kurap, walang mahirap,” came back to haunt him in 2013 as the country was rocked with one of the biggest political scandals in recent history, when businesswoman Janet Lim Napoles, along with a number of prominent politicians, defrauded the Philippine government of close to P10 billion through the misuse of the Priority Development Assistance Funds (PDAF) or “pork barrel.” That same year, Aquino again drew ire for the government’s delayed and poorly-coordinated response to Typhoon Yolanda. Two years later, Oplan Exodus in Mamasapano saw severe public scrutiny for its unusually high body count, in addition to the involvement of then-suspended police chief Alan Purisima, in what has since been dubbed the biggest loss of government elite forces in the country’s history.

It should come as no surprise then that, by the end of his presidency, PNoy had seen all the goodwill the Aquino name had accumulated dissipate in front of him, usurped by a new upstart from Davao who now benefited from the same backlash against government he once benefited from with Arroyo. If you were to ask voters in 2016 what they thought of the Aquino presidency, doubtless the answers would have been “unremarkable,” “unexceptional,” “wala namang nagawa,” “walang pagbabago.” Needless to say, the mob is fickle, and that appraisal, I believe, was one of our gravest injustices against Noynoy Aquino.

Aquino was many things: a bachelor, an economist, a reformer, a pragmatist, an oligarch, a neoliberal, a “disaster president” – “tuta ng imperyalismong US,” as many on the Left like to call him – but unremarkable was never one of them. I had levied my fair share of criticisms against the Aquino administration. His tenure was, after all, the period of my political awakening. But despite all his imperfections, all his failures as our chief executive, I can only say that he was a man who did what he could, when he could, with what he was given. The typical stoicism with which Aquino faced hurdle after hurdle thrown at his presidency, long mistaken to be callousness and aloofness on his part, seemed to me now a staunch commitment to keeping his personal emotions from interfering with policy decisions.

I do not intend, nor could I intend, to sanitize the legacy of so complicated an individual. But as the dust settles and we find ourselves looking back at the Aquino presidency with clearer eyes, I believe it important that we remember the good alongside the bad.

Beyond his economic successes, Aquino surrounded himself with the best and brightest government had to offer. His administration saw the appointments of Maria Lourdes Sereno to the Chief Justiceship and Conchita Carpio-Morales to the Office of the Ombudsman. It saw the successful impeachment of Arroyo’s midnight appointee, Chief Justice Renato Corona, and the indictment and suspension of Senators Juan Ponce Enrile, Jinggoy Estrada, and Bong Revilla. He pardoned Trillanes and the rest of the Arroyo mutineers because he understood that reconciliation was integral to a functioning democracy. In that same vein, Aquino made great strides to ending the decades-old conflict in Mindanao. Despite the infamous debacle that was Mamasapano, Aquino’s determination to bring peace to the region resulted in the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB), in which the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) and its armed wing, the Bangsamoro Islamic Armed Forces (BIAF) agreed to lay down their arms in return for the creation of an autonomous Bangsamoro.

But what was his crowning achievement – and this, I would say, is a near unanimous appraisal – is the unwavering resolve to ensure the country’s sovereign rights in the West Philippine Sea in the face of Chinese premier Xi Jinping’s, and to a certain extent his predecessor Hu Jintao’s, aggressive foreign policy, embarking on a modernization program to equip the country’s aging military. Aquino’s dogged resistance to Chinese incursion, alongside the likes of former Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario, former Associate Justice Antonio Carpio, and then Solicitor General Florin Hilbay, among others, culminated in a landmark victory at the Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), cementing in the international community the legitimacy of our claims – a victory which has, unfortunately, been tossed to the wayside by Aquino’s successor.

Being sentimental for a politician is quite unlike me. Part of me had always wondered why Aquino never returned to public life following his presidency. Part of me had always felt he had evaded responsibility for much of the controversy surrounding his administration. Looking back at the past few years, and knowing what I know now, I understand a little better why things had turned out the way that they did. When, finally, he resurfaced after a long absence to answer for the Dengvaxia controversy, admittedly looking a little worse for wear, we did not see a neck brace, nor a wheelchair, nor any appeal to pity characteristic of his predecessors in times of trouble. Aquino faced the Filipino public with the stern and taciturn demeanor of a man who, in his heart, had always believed himself to have acted in the public interest. For that, I cannot help but express some long overdue admiration for a president I had long been critical of. Was he the country’s best? I doubt it. Was he the country’s worst? Far from it. But I could say with confidence: Noynoy Aquino was probably one of the better ones.

In any case, the Aquinos continue to cast a looming shadow over this country’s politics, even after the passing of its most distinguished members. I expect the coming days, weeks, perhaps even months, to be awash with deserved fondness and equally deserved criticism of the late Benigno Aquino III. I myself, at least, have made my peace with it. But if there is anything the Aquinos have taught me, despite my constant disappointment both in them and in the sorry state of this country, it is this: the Filipino is worth dying for; the Filipino is worth living for; the Filipino is worth fighting for. One need not be a fan of them to know that much to be true. – Rappler.com

Kyle Parada is a Political Science undergrad and occasional essayist studying in the Ateneo de Manila University. His research interests include Ideology, Political Theory, International Relations, and Global History.

Voices features opinions from readers of all backgrounds, persuasions, and ages; analyses from advocacy leaders and subject matter experts; and reflections and editorials from Rappler staff.

You may submit pieces for review to opinion@rappler.com.

Add a comment

How does this make you feel?

![[EDITORIAL] Marcos, bakit mo kasama ang buong barangay sa Davos?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2023/01/animated-marcos-davos-world-economic-forum-carousel.jpg?resize=257%2C257&crop_strategy=attention)

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.